Some would be dissatisfied with the state government’s explanation that it was a “systems failure” that tragically killed one newborn baby and seriously injured another when the wrong gas was connected to an outlet in the operating theatre of a Bankstown hospital.

But, NSW Secretary of Health Elizabeth Koff was right when she said “we failed as a system”. It is systems, not individuals, that are responsible for devastating errors in complex organisations like hospitals. And it is also here that potential solutions lie.

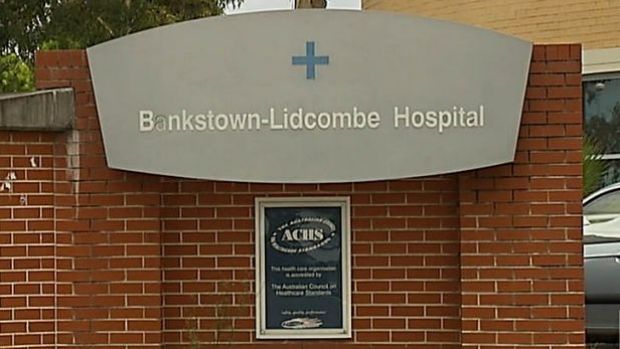

New South Wales Health Minister Jillian Skinner expresses her “profound sorrow” after gas mix-up kills one baby and leaves another in a critical condition at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. Vision courtesy ABC News 24

It is difficult to imagine circumstances more devastating than the needless death or injury of a newborn child. For every serious error that occurs in our hospitals, particularly one that takes a life, a “no stone unturned” investigation or inquiry is, of course, essential, as is the support of all those affected.

Yet, when things go seriously wrong in our modern healthcare systems we tend to respond in the same knee-jerk, but ultimately ineffective, way. We want to “find and fix” the error. We devote considerable resources to reverse engineering exactly what went wrong with the worthy intention of learning from our mistakes, so that something similar will never happen again.

Our confidence in whatever new protocols, processes or recommendations follow is, however, often misplaced. No matter how many investigations are conducted and what we do learn, healthcare delivery is so complex that virtually no serious error ever occurs in the same way again. In the meantime, by identifying the exact point at which a process was derailed, we often find human error has played a part, paving the way for the laying of personal blame.

We’ve spent much of the past 25 years looking at patient safety through this “find and fix” lens and we’ve seen healthcare professionals and others scapegoated in the process. Yet, error rates have remained stubbornly and unacceptably high.

One in every 10 patients in our hospitals is actually harmed by our healthcare system through errors, omissions or miscommunication. Mostly this is minor harm, like tolerable changes in the dosage of a drug, for example. But many patients acquire infections and some patients are made much sicker or die as a result of a confluence of decisions and events along their complex patient journey.

The Productivity Commission identified 107 serious medical errors in the Australian health system in 2012, from instruments being left inside patients and operations being carried out on the wrong patient or body part, to medication errors resulting in death. Medical error rates are similar in most industrialised countries.

Nitrous oxide was given to two newborn babies at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. Photo: SMH

Nitrous oxide was given to two newborn babies at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. Photo: SMH

Clearly, we need a different approach. I am not suggesting we divert our focus from cases such as the recent newborn tragedy. These need to be, and will be, thoroughly investigated. What I am suggesting is that we must also consider the bigger picture; that is, how our healthcare systems do, or do not, work.

Modern healthcare systems are perhaps the most complex systems humanity has ever built. In Australia, like most advanced economies, some 9.3 per cent of GDP is now spent on healthcare, that is some $180 billion a year, and about the same per cent of our workforce is needed to deliver care, some 600,000 people. For healthcare systems to deliver the right care to the right patients at the right time, every single staff member and consultant, every single computer, every single medical device and every drug must not only work as it should, but every person and piece of technology and software within this complex web must also communicate effectively.

NSW Health Minister Jillian Skinner and Secretary of Health Elizabeth Koff hold a press conference about the baby death at Bankstown Hospital. Photo: Janie Barrett

NSW Health Minister Jillian Skinner and Secretary of Health Elizabeth Koff hold a press conference about the baby death at Bankstown Hospital. Photo: Janie Barrett

As a healthcare systems researcher, I routinely unravel the multitude of interactions that must take place to ensure our teams of doctors, allied healthcare professionals and administrators deliver the best possible care. Our doctors, nurses, administrators and support staff are overwhelmingly committed to their patients and to safety and are intuitively nearly always right. Nine out of 10 hospital patients receive exemplary care. It is within this apparently routine success that the answer to systems failures may lie.

Instead of merely scrutinising mistakes, patient safety experts worldwide are now actively seeking to understand how and why health systems work well, so that the lessons of success, like effective health teams and proven safe behaviours, for example, can be spread. To protect patients and improve healthcare we need to understand what a healthcare system looks like when it’s performing at its resilient best, flexing and adjusting to accommodate the unexpected.

By constantly looking backwards to find and fix we risk merely applying a new Band-Aid for each new failure. The Band-Aids build up and the new ones can get in the way of the old ones.

We’re already gaining some important insights. Hospital systems function at their very best when certain factors coincide like a positive organisational culture, a receptive and responsive senior management team, active performance monitoring, a proficient workforce, effective clinical leadership, and sound teamwork. By learning more about successful systems and by driving evidence-based organisational-wide changes we have our best chance of heading off failures, and patient harm, before they arise.

Professor Jeffrey Braithwaite is founding director of the Australian Institute of Health Innovation at Macquarie University.