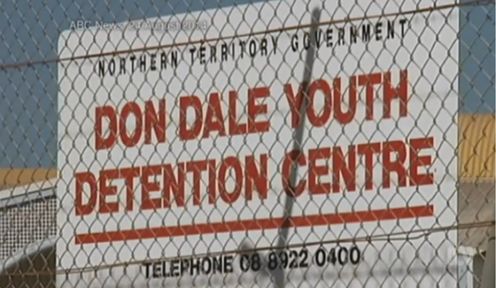

The forthcoming royal commission should bring recommendations that could improve the future treatment of young people in juvenile detention. AAP/Four Corners

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s prompt and decisive response to Monday night’s Four Corners program on the torture of young people at Don Dale Youth Detention Centre is welcome. The forthcoming royal commission should bring important and high-profile recommendations that could improve the future treatment of young people.

But these pictures, although shocking, should not have surprised anyone with an interest in the welfare of incarcerated children. Turnbull is not correct to say that previous inquiries did not turn up evidence of this treatment.

It is more accurate to say that the two inquiries produced different conclusions, reducing their impact.

The restraints that produced such disturbing pictures were approved by the Northern Territory parliament and highly publicised at the time. The incident in August 2014 that led to the use of the tear gas has already been subject to two inquiries.

Michael Vita’s 2015 report, on behalf of the NT government, takes quite a defensive tone. It describes the action in the centre on the day as “justifiable”, and asks those who criticise the action of guards to take the volatile context, the poor infrastructure, and the background of the detainees into account.

The report acknowledges some failings and makes some suggestions for change, although most of these are at an operational rather than strategic level.

Somewhat unusually, the report challenges civil liberty groups for criticising but not putting forward specific suggestions, and criticises “Aboriginal legal and justice agencies” for not spending time in institutions running programs. These comments add to the impression of a report prepared for political reasons rather than as an objective attempt to uncover the truth.

The NT children’s commissioner (initially Howard Bath, then Colleen Gwynne) investigated the 2014 incident, in an own-initiative report. It found the children, some as young as 14, were tear-gassed, had fabric hoods placed over their heads, and were deprived of drinking water for 72 hours in solitary confinement.

The report challenged the description of the events as a “riot”, saying there was no unlawful assembly and that, in one instance, children were gassed in their room when playing cards.

Re-reading the children’s commissioner’s report after watching the Four Corners program, it is striking how accurate a description of events is provided. At the time the NT corrections commissioner, Ken Middlebrook, condemned the report as inaccurate and one-sided. His response, along with the Vita report, seemed to provide enough political cover to enable the children’s commissioner’s report to be ignored by both the NT and federal governments.

The problem with youth custodial institutions is not that we don’t know the impact they have on young people. It is that we lack the political will to tackle them.

This is perhaps because the questions are so big and the required response is so significant that it is impossible to properly discuss how we treat young people in Australia without linking their treatment to history, race and gender.

The default response to young people who offend seems to be to exclude them from society and from visibility – a response that runs right through Australia’s history. We know that Aboriginal young people are massively disproportionately likely to be incarcerated, and this disproportion is particularly marked in the NT.

The Australian state judges and punishes Aboriginal parents for perceived shortcomings in how they bring up their children. But Four Corners showed starkly what can happen to an Aboriginal child when that state takes on the role of parent.

Gender issues are important too. Young people in the community are primarily looked after by an army of professionally trained women – usually by teachers but, when necessary, by social workers, counsellors and psychologists. However, the most troubled children who exhibit the most troubling behaviour are left in the custody of a group of men within the most macho, confrontational and violent culture.

The children’s commissioner recommended that Don Dale be closed; it is difficult to disagree with that recommendation. But it is not enough for Don Dale simply to be replaced by a newer facility with more accountability and better-trained staff (although all three of those things are needed).

What would demonstrate a genuine commitment to these children – most of whom are Aboriginal – is a radical change in approach to juvenile justice in line with international instruments and best international practice.

Australia should ratify the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention Against Torture. Raising the age of criminal responsibility to 14 would not only protect children under that age, but also require organisations and society at large to find different responses to children who offend. This impacts on older children too.

Detention should genuinely be used as a last resort; this requires the design of interventions in the community for high-risk offenders. Where detention is used, facilities should be small, local and staffed by professionally qualified and properly trained workers.

It may well be true that there has been a culture of cover-up in the NT but there is also, clearly, a culture of complacency among decision-makers. It is Aboriginal children who are most affected, so now is the time for Aboriginal leaders and elders to be included in the leadership and decision-making processes about what happens to their children.

Brian Stout does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.