When Erika Schneider had surgery to address a common nasal complaint in the early 2000s, she was expecting a relatively speedy recovery.

The operation to fix her allergy symptoms and snoring was fairly routine. It was an easy outpatient surgery, to correct a deviated septum — the thin bony structure in the centre of the nose.

“I wasn’t going to have to stay overnight. I just didn’t think it was going to be that big of a deal, and I was not told of any complications,” she said.

Unfortunately what followed was more than a decade of pain, discomfort and sleepless nights — underpinned by an alarming sensation.

To this day, Ms Schneider feels like she can’t breathe, and you can hear it in her voice.

“My nose felt very dry, all the time, but at the same time it also felt very congested. It makes you feel like you can’t breathe, and I guess that is suffocating,” she said.

You feel it pretty much all the time, and that makes you start to panic. Your brain just goes to, ‘Oh my God, I can’t breathe, I need to treat this’.

After 13 years of searching for a doctor who could tell her why she felt this way, she was finally diagnosed with empty nose syndrome.

But it was a diagnosis that threw up an entirely new set of challenges — including being faced with the prospect of having tissue from a cadaver implanted in her nose.

What is empty nose syndrome?

Steven Houser is the doctor who eventually diagnosed Ms Schneider with empty nose syndrome.

He is an ear, nose and throat specialist, or otolaryngologist, from Cleveland, Ohio in the United States, who is at the forefront of trying to figure out exactly what is going on with empty nose syndrome.

Dr Houser says patients with empty nose syndrome, which is very rare, have usually had some type of surgery done on their nose, and yet they actually feel worse.

“What patients will often times describe to me is that they are actually suffocating,” he said.

“They just know it does not feel right in terms of their breathing, despite having surgery to try to help their breathing.”

Many patients say the feeling is akin to having really bad hay fever.

But when a doctor looks inside their nose, usually the very opposite is true, and the nasal passages are clear.

“It’s a paradox,” Dr Houser said. “They are wide open and yet they feel so blocked.”

“This part of the problem that these patients run into as well — is that they will have seen multiple doctors who look in their nose and say, ‘What are you talking about, you can’t breathe through your nose? I could drive a truck through your nose, your nose is wide open, what’s going on here, this makes no sense.’

“And this is where they end up then a lot of them potentially getting depressed and feeling like the medical establishment cannot help them at all.”

Dr Houser says for some patients, the affects of empty nose syndrome really do go well beyond the physiological.

“People will describe to me that they are just constantly thinking of their nose,” Dr Houser said.

“Their sleep is often affected, they have poor sense of smell … [and] there is oftentimes a very high level of anxiety.

“They really can’t get any work done, they end up losing jobs and losing relationships, getting divorced because they really can’t think of anything other than the fact that they can’t breathe. And that’s occurring 24/7.”

Turbinates, scissors and nasal mucosa

To understand empty nose syndrome, it helps to be familiar with the basic anatomy of the nose.

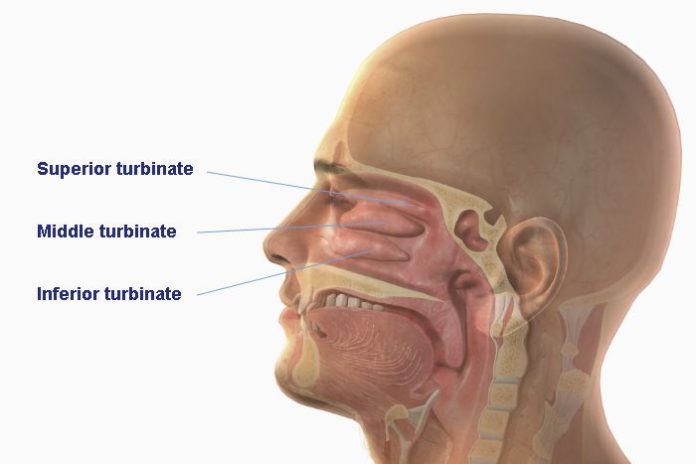

In the centre of the nose lies the nasal septum, a thin bony structure that separates the nostrils, and then on either side of this, there are three pairs of what are called turbinates.

The superior turbinates sit at the top of the nasal cavity, the middle turbinates in the middle and the inferior turbinates below these.

“The inferior turbinate is a large turbinate in the nose that is probably about the size of a person’s index finger on each side, and basically it has a lot of vascular tissue within that can swell and shrink and it can help block the airway as a result,” Dr Houser said.

Sometimes in patients with chronic nasal blockages and sinus problems, doctors need to reduce the size of the inferior turbinate in order to allow them to breathe better.

Doctors are still not entirely sure what causes empty nose syndrome and some are still sceptical about whether it exists at all. But studies indicate that damage to the inferior turbinate structures during surgery is, at least somewhat, responsible for empty nose syndrome.

According to research by Dr Houser, about 20 per cent of patients who undergo a total inferior turbinate resection (a rare procedure in which scissors are used to remove the entire turbinate) develop empty nose syndrome.

But it’s not just structural damage to the turbinates that causes the condition.

Nerves inside the nasal mucosa, which lines the nose and helps moisten the air before it enters the lungs, also play a role.

“The nerves that are responsible for sensing the airflow [can also be] damaged in the process of removing this tissue,” Dr Houser said.

“They typically actually will recover and will grow back … but in select cases there are patients that never have recovery of function, and they then develop these symptoms of empty nose syndrome.”

What this all means is that the patient’s ability to feel the movement of air through their nose is impaired — and this is what doctors believe causes the “suffocating” sensation.

So if turbinate surgery can have such dire consequences — why do it at all?

And according to Dr Houser, there are now safer methods available for reducing the turbinates, which stay away from the lining and don’t involve blunt objects like scissors. These newer methods include the use of radiofrequencies and a special surgical cutting tool called a microdebrider.

“And I think the argument could be made that it would be wise for us to reduce turbinates judiciously with these techniques, rather than with using scissors to cut out tissue,” Dr Houser said.

The treatment? Tissue from a dead person

After the operation to correct her deviated septum, Ms Schneider had two follow-up operations on her turbinates, in an effort to fix the strange sensation in her nose — neither of which helped.

“By the time I had this third thing done I realised, OK, surgery is the problem,” she said.

“I started looking online and I found Dr Houser’s group, and I just thought, OK, this is what I have, there is no doubt that I have this condition.”

But what is it exactly that Dr Houser does when he encounters a patient with empty nose syndrome?

“When patients contact me about empty nose … moisture is going to be very important, typically utilising saline sprays, saline jellies and nasal oils,” he said.

“Frankly patients need to experiment and see what feels best inside their nose. Everyone is a little bit different, so I don’t have an exact recipe as to what will get people feeling the best. But they need to experiment with some of those to see what gets them feeling as good as they can be.”

He also does what he calls “the cotton test”.

“We literally are taking cotton, usually about half a ball or so, and moistening that with saline and placing that into the nose … usually in the area where the patient is missing tissue, and then seeing how that affects them in terms of their breathing,” he said.

For Ms Schneider, as for many other patients, the effects were instant.

“He put this wet piece of cotton in there, and it blocked off a lot of my nose, but it felt a more natural,” she said.

“Having a foreign piece of material in my nose felt more natural … So I was like, cool, it kind of confirmed that this is what I have.”

The principle behind the cotton test is also the thinking behind a more radical way to treat the syndrome: a turbinate transplant, which Ms Schnieder underwent after meeting Dr Houser.

In this operation, instead of cotton, the empty nose is filled with an implant made of cadaver tissue, called AlloDerm.

“They’ve taken tissue from a dead body and cleaned it, and it can be grafted into your nose to exist as a placeholder, to give the air the resistance that it needs to go through your airway,” Ms Schnieder said.

“Because without it, it’s like a plane trying to lift off without this resistance. The air just sits there and is turbulent and won’t flow through your airway, and that’s what leads to that suffocation feeling. But it doesn’t replace the function of your turbinates. You still have a lot of the same symptoms … it’s just a bit less.”

Transplants saving lives

Ms Schnieder had two cadaver implants, which helped for a while, but were not a permanent solution.

But for other patients, Dr Houser says an implant can be transformative.

“Some of these patients then when I managed to implant them and see them back six months later … it’s a world of difference. These patients are so much more at peace and calm and it’s clear that their nose was really ruling their lives,” he said.

Some of Dr Houser’s patients even credit him with saving their lives.

“I have to tell you, I’ve had 15 to 20 patients who have told me that my surgery kept them from committing suicide,” he said.

“I do a lot of sinus surgery … sleep apnoea and so forth, and those are surgeries that help people’s quality of life … but a lot of times, the empty nose surgery that I do can actually save someone’s life.”