Something strange is going on in medicine. Major diseases, like colon cancer, dementia and heart disease, are waning in wealthy countries, and improved diagnosis and treatment cannot fully explain it.

Scientists marvel at this good news, a medical mystery of the best sort and one that is often overlooked as advocacy groups emphasise the toll of diseases and the need for more funds. Still, many are puzzled.

“It is really easy to come up with interesting, compelling explanations,” said Dr David Jones, a Harvard historian of medicine. “The challenge is to figure out which of those interesting and compelling hypotheses might be correct.”

These diseases are far from gone – they still cause enormous suffering and kill millions each year – but the list of killers that seem to be declining without full explanation is varied and striking.

Humans cannot, of course, cheat death. But it looks as if people in the United States and some other wealthy countries are, unexpectedly, starting to beat back the diseases of ageing. The leading killers are still the leading killers – cancer, heart disease, stroke – but they are occurring later in life, and people in general are living longer in good health.

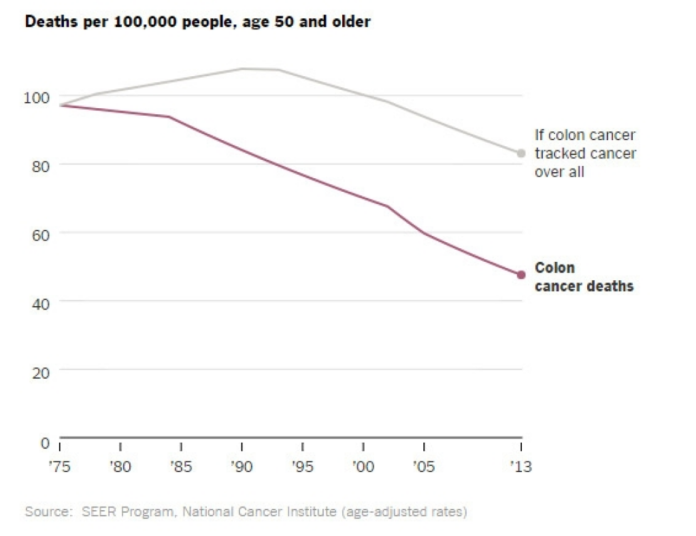

Colon cancer is the latest conundrum. While the overall cancer death rate has been declining since the early 1990s, the plunge in colon cancer deaths is especially perplexing. The rate has fallen by nearly 50 per cent since its peak in the 1980s, noted Dr H Gilbert Welch and Dr Douglas Robertson of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and the Veterans Affairs Medical Centre in White River Junction, Vermont, in a recent paper.

Screening, they said, is only part of the story. “The magnitude of the changes alone suggests that other factors must be involved,” they wrote. None of the studies showing the effect of increased screening for colon cancer has indicated a 50 per cent reduction in mortality, they wrote, “nor have trials for screening for any type of cancer.”

Then there are hip fractures, whose rates have been dropping by 15 to 20 per cent a decade over the past 30 years. Although the change occurred when there were drugs to slow bone loss in people with osteoporosis, too few patients took them to account for the effect — for instance, fewer than 10 per cent of women over 65 take the drugs.

Perhaps it is because people have gotten fatter? Heavier people have stronger bones. Heavier bodies, though, can account for at most half of the effect, said Dr Steven Cummings of the California Pacific Medical Centre Research Institute and the University of California at San Francisco. When asked what else was at play, he laughed and said, “I don’t know”.

Dementia rates, too, have been plunging. It took a few reports and more than a decade before many people believed it, but data from the United States and Europe are becoming hard to wave off. The latest report finds a 20 per cent decline in dementia incidence per decade, starting in 1977. With more older people in the population every year, there may be more cases in total, but an individual’s chance of getting dementia has gotten lower and lower.

There are reasons that make sense. Mini-strokes result from vascular disease and can cause dementia, and cardiovascular risk factors are also risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. So the improved control of blood pressure and cholesterol levels should have an effect. Better education has also been linked to a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease, although it is not known why. But the full explanation for the declining rates is anyone’s guess.

The exemplar for declining rates is heart disease. Its death rate has been falling for so long — more than half a century — that it’s no longer news. The news now is that the rate of decline seems to have slowed recently, although it is still falling. While heart disease is still the leading cause of death in the United States, killing more than 300,000 people a year, deaths have fallen 60 per cent from their peak. The usual suspects – better treatment, better prevention with drugs like statins and drugs for blood pressure, and less smoking – are, of course, helping drive the trend. But they are not enough, heart researchers say, to account fully for the decades-long decline.

The heart disease effect has been examined by scientist after scientist. Was it a result of better prevention, treatment, lifestyle changes?

All three played a role, researchers said.

Dr Jones said the current explanation reminds him of the Caucus-race in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in which the Dodo, officiating, declared that “EVERYBODY has won, and all must have prizes.”

It’s not as if the waxing and waning of diseases have never happened before. And all too often these medical mysteries remain mysteries.

Until the late 1930s, stomach cancer was the No.1 cause of cancer deaths in the United States. Now just 1.8 per cent of cancer deaths in the United States are from stomach cancer. No one really knows why the disease has faded. Perhaps it is because people stopped eating so much food that was preserved by smoking or salting, or maybe it is because so many people took antibiotics that H. pylori, the bacteria that cause it, have been squelched.

In the 19th century, experts tried to explain why tuberculosis was a leading killer. That’s what happens when people live in cities, doctors said, and there is little to be done. By the start of the 20th century, one out of every 170 Americans lived in a tuberculosis sanitarium.

Then, even before the eventual development of drugs effective against it, TB started to go away in the United States and Western Europe. But experts disagree about why. Some say it was improvements in public health and sanitation. Others say it was changes in medical care. Others split the difference and say it was both.

The tuberculosis surprise was eclipsed in the 1930s as heart disease became ascendant. It would kill us all, the experts said. And sure enough, by 1960, a third of all US deaths were from heart disease. Now cardiologists are predicting it will soon fall from its perch as the leading killer of Americans, replaced by cancer, which itself has a falling death rate.

Predicting future trends, Jones noted, “is often a suspect science in which slight changes in assumptions lead to substantial differences in projected futures.”

But Cummings has a provocative idea for further investigation. He starts with two observations: Rates of disease after disease are dropping. Even the rate of “all-cause mortality,” which lumps together chronic diseases, is falling. And every one of those diseases at issue is linked to ageing.

Perhaps, he said, all these degenerative diseases share something in common, something inside ageing cells themselves. The cellular process of ageing may be changing, in humans’ favour.

“I want to look inside cells,” Cummings said. Inside, there could be more clues to this happy mystery.

The New York Times