HIV researchers have made headlines in Australia by declaring an end to AIDS as a national public health issue, three decades after the devastating immune deficiency syndrome was first diagnosed locally.

With more than 35,000 HIV infections recorded in Australia since the outbreak began and an estimated 9,900-11,000 deaths, the reduction in AIDS cases to negligible levels is welcome news.

Australia has long been at the forefront of global efforts to combat HIV/AIDS, and advances in anti retroviral therapy mean very few people who contract the virus now die from the full syndrome.

For the full story, Croakey‘s Amy Coopes has this piece over at the BMJ.

Activists have cautiously welcomed the announcement, though The Institute of Many cofounder Nic Holas notes it is not breaking news, with AIDS ceasing to be a notifiable disease in Australia some years ago — “the culmination of a slow and lengthy process requiring decades of hard work in the midst of much loss and resulting trauma”:

That hard work deserves to be reported on far and wide. Australia really is one of a few places to have essentially ended AIDS. There remain some instances of HIV+ women and recently-arrived HIV+ people (and others) in Australia unfortunately still being diagnosed with AIDS, often due to not being tested for it. This is not because they are bad at getting HIV tests, but because they are often left out of health promotion. This needs to be addressed, but as the article suggests many of these AIDS diagnoses are caught in time so that treatment can commence. AIDS is no longer certain death.

One only has to hop across to PNG to see how HIV/AIDS continues to wreak havoc, as it has done for decades. That is partly why I think this article exists. The Australian Government is yet to commit to replenishing The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Next week is the International AIDS Conference in South Africa. This is a timely piece of media to remind our re-elected government that Australia is a world leader in HIV/AIDS, and that leadership means we cannot abandon the rest of the Asia-Pacific region.

It’s worth reading his post in full, but among his other points (reproduced here with permission):

- the end of AIDS does not mean the end of stigma for HIV positive people, with criminalisation, employment bans and exclusion still very much a reality

- vigilance is needed in highlighting the difference between AIDS and HIV, but infection rates of the virus have been stable for the past few years

- there is no need to assume that these reports will result in the abandonment of safe sex practices based on “over 30 years of sexual health promotion”

- this announcement does not mean the blood donation ban on men who have sex with men should end – “If you are a gay/bi man passionate about being able to donate blood, the fastest way to do that will be to end HIV in Australia. We ended AIDS, we can do the same with HIV.”

- the data and discussions are dominated by experiences of mainly white gay men in Australia’s major cities, but important work is being done in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, where ownership of efforts and Closing the Gap strategies remain vital

Health promotion consultant and ANU PhD candidate Daniel Reeders has also taken a look at the news over at his blog Bad Blood, and has kindly permitted us to cross-post his analysis below.

Daniel Reeders writes:

My supervisor messaged me: “ABC news right now – the end of AIDS as a public health issue.” Fairfax was reporting it too:

AIDS epidemic ‘over’ in Australia, say peak bodies

Australia’s peak AIDS organisations and scientists have announced an end to the AIDS epidemic, as the country joins the few nations in the world to have beaten the syndrome.

The number of annual cases of AIDS diagnoses is now so small, top researchers and the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations [AFAO] have declared the public health issue to be over. (Saimi Jeong, The Age 10 July 2016)

In blog posts and feature articles for some time now, I’ve been arguing that media framings, policy-making and popular understandings of HIV have lagged behind reality, holding onto notions of the ‘AIDS crisis’ and HIV as a deadly disease.

These ‘zombie notions’ impede sensible policy-making around prevention, such as the removal of outdated HIV-specific laws, and public funding for pre-exposure prophylaxis — medication that protects HIV-negative people from infection during condomless sex.

Gary Dowsett first conceptualised ‘post-AIDS’ thinking among gay men in 1996. In 2004, at a plenary session of the HHARD and HIV Educators’ conferences, I described myself as ‘pre-AIDS’ — born in 1981, coming out to myself in the mid-90s, the ‘AIDS crisis’ was over in the gay community before I ever joined it, and I’d had to reconstruct an understanding of what it had meant for the people around me. More recently, cultural studies scholar and critic Dion Kagan wrote his PhD on ‘post-crisis’ meaning-making around HIV, along with a stellar series of columns exploring this theme in The Lifted Brow.

I understand the messaging from AFAO and celebrity scientist Prof Sharon Lewin in this context. At first I wondered what it was about. I think there are three things going on:

- The number of people dying from AIDS, rather than dying with HIV, is now so low it violates statistical conventions against reporting cell sizes under 5.

- AFAO might have wanted to shift the media and policy narrative and ‘claim a win’ to count against what’s starting to look like the inevitable failure of ‘Ending HIV‘.

- Australia wanted an ‘announceable’ going into the AIDS2016 conference in Durban.

A number of people have expressed concern to me that this announcement obscures the reality of ongoing, smaller AIDS crises in particular groups, including migrants and refugees, especially those who lack access to Medicare, and Aboriginal communities.

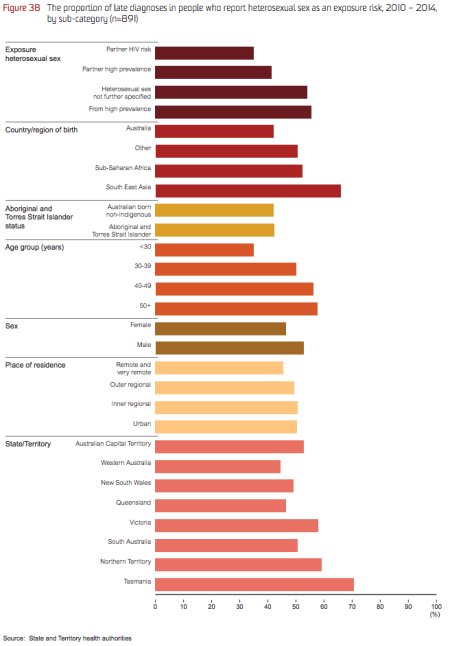

Since 1996 we no longer focus on deaths from AIDS nor even AIDS diagnoses — early diagnosis and treatment are the ballgame. People with late diagnosis, defined as a t-cell count below 350 per millilitre of blood, have elevated lifetime risk of serious illness, including cardiovascular events like heart attack, even after they start on treatment.

<p><img class=”aligncenter wp-image-40749 size-full” src=”https://croakey.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/screenshot-2016-07-11-08-05-47.jpg” alt=”screenshot-2016-07-11-08-05-47″ width=”450″ height=”646″ /></p>

Source: Kirby Institute, Annual Surveillance Report 2015 p51 (pdf)

In other health issues, such as cancer screening, the identification of lower rates of screening in specific communities compared to the Victorian population average has been used to target them for additional funding and recruitment initiatives. But the danger is always that small clusters get swept under the carpet, protected from identifiability by that convention against reporting cell sizes under 5.

My concern about this messaging is that it depends on policy-makers understanding that AIDS is not a journalistic synonym for HIV.

If they don’t, this message will look like a green light to ‘mainstream HIV’ — ditching peer based services and funding hospitals, nurses, social workers and MPH grads to ‘mop up’. That would be moreexpensive than community-based services, but it would restore what the health system views as the natural way of doing things — top down, expert-led.

Bernard Gardiner, a PhD scholar working on a qualitative longitudinal study of aging, place and social isolation among people living with HIV in Queensland, and a respected elder of the Victorian gay community response to AIDS, puts it this way:

I think this is careless. This takes the pressure off Public Health officers working for Government, who see psycho-social support services for long-term survivors as unnecessary ‘hand-holding’ that Gov should not fund. It also disguises the reality that some long-term survivors struggle for quality of life with depression, multiple co-morbidities, cognitive issues, cancers/heart/renal issues, and poverty, and feel somewhat abandoned by the biomedical 90/90/90 focus.

Once upon a time a shift like this would have been thoroughly debated among the AFAO membership and communicated to affected communities via community media. This would have provided an opportunity to prepare for the secondary messaging that will be necessary to make sure this message doesn’t backfire. We live in interesting times.

Daniel Reeders is a health promotion consultant and PhD candidate with the Australian National University’s Regulatory Institutions Network