It seems as though one of the few clear points of difference between the major parties in this election campaign is the position on the freezing of Medicare rebates. For a very readable background to this issue you can do no better than reading this article on The Conversation by Associate Professor Helen Dickinson.

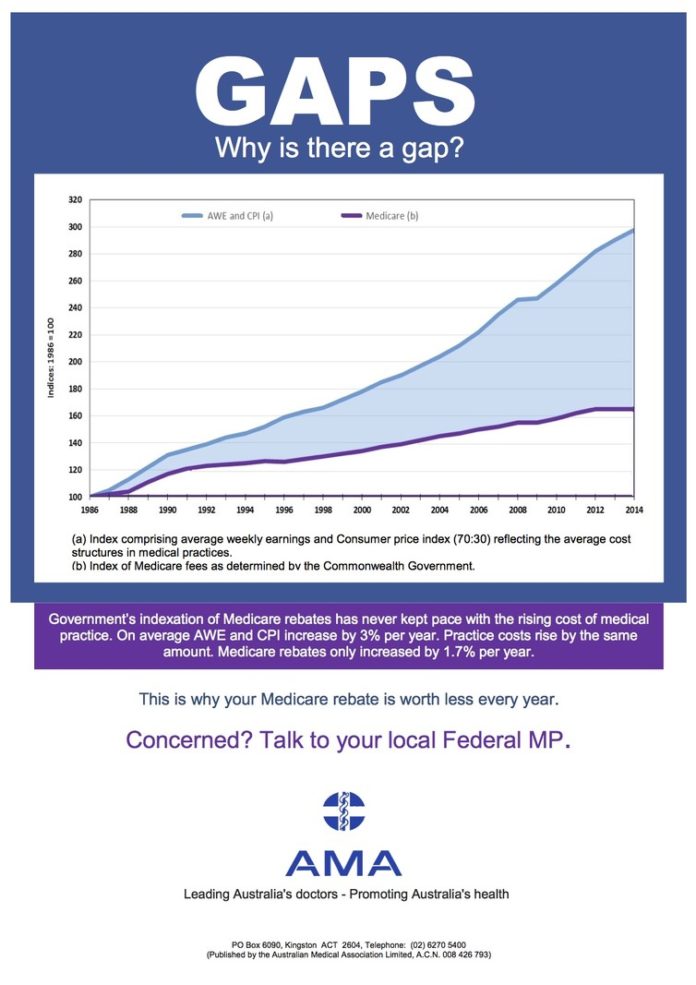

When Medicare first began in 1983, it covered visits to general practitioners at a level which was generally agreed to reflect the cost of providing the service, minus a small discount which was supposed to compensate for the ease of bulk billing services. The chart below, produced by the Australian Medical Association (AMA), shows the difference between the incremental increases in Medicare rebates and the steadily rising cost of providing the services those rebates are meant to cover.

Within the medical profession these days, the AMA price is felt to reflect a fair fee for services provided by doctor-owned practices with all the associated overheads of an inefficient small business. Many specialists and GPs I know charge well under this rate. A handful charge in excess of it. It’s a business decision based on the circumstances and ambitions of the doctor, much like prices in any market.

The coalition has traditionally had an ambivalent relationship with bulk billing. The perception of a free service at point of care fills conservative ideologues with righteous anger. Yet evidence of increased bulk-billing rates is held up as political gold and a sign of healthy policy settings.

In my opinion, recent increases in bulk-billing rates are not due to policy decisions but to large corporate general practice companies developing effective business models to make bulk-billing centres cost-effective. Such centres are a mixed blessing in general practice land.

Imagine a small country town with a privately-billing, locally-owned general practice. The GPs in that practice also cover the hospital and have a roster for after-hours care. Such care is only possible when it is appropriately billed for as reception staff have to work long hours, GPs need to pay locums when on holiday and vital practice infrastructure needs to be maintained. Who knows, the GPs themselves may even need to be protected from burnout and stress by occasionally taking a holiday.

Such a practice provides quality care to its community but waiting times for routine appointments are often long and the rebates available by bulk billing are not enough to sustain the cost of such a practice. Most such practices have already abandoned bulk-billing for patients without concessional entitlements such as Health Care Cards.

Across the road from this practice in the small town there opens a corporate-owned bulk billing centre. This practice will be popular with locals who may have relatively straightforward problems or who have financial circumstances that dictate their needing bulk-billed care. It is unlikely to be open extended hours or provide GPs who will cover the hospital, as these practices need to stick closely to a business model in order to be sustainable. There will be an increase in bulk billing in the town, but will they be the services that people really need in the manner that they are best provided?

Ensuring financial viability in bulk-billing practices risks leading to substandard medicine despite the best intentions of those involved. For example, a doctor who orders an X-ray of a suspected fracture will not be allowed to see the patient following the X-ray being taken as this repeat attendance cannot be bulk billed for. Similarly, some bulk-billing practices will not allow doctors to prescribe more than the minimum amount of medication at any visit, ensuring patients have to come back within a couple of weeks for more scripts.

Now imagine the business case for a bulk-billing clinic where the income for a given volume of patients will not increase for seven years. The rents will increase. The wages of employees will increase. The cost of utilities will increase. Pretty much all the costs will increase, but the income won’t.

Who would start such a business? What strategies might become necessary to maintain the current thin margin of profitability? You could increase the volume and run the risk of being accused of “six-minute medicine” by politicians and the community. It would make much more sense to introduce a co-payment.

And there we have the reason for the AMA and others referring to the rebate freeze as a “co-payment by stealth”. The government would be well aware of the business realities that GPs face. They have learned from last year’s fiasco that co-payments are electoral poison if introduced by the parties. They even seem to be trying to backpedal from any perception they really want it in place. So why not do nothing and force GP practice owners into doing it for them?

The Labor Party has committed to reintroducing some type of indexation but that is not nearly enough to improve things. At best it might preserve the status quo. The debate about health funding has sunk so low that beleaguered GPs are simply grateful if the federal government promises not to bankrupt their practices. Left in place, the rebate freeze will make bulk-billing unsustainable for the corporatised practices who drive the current high rate. This will make basic services less affordable, and predictably throw a greater burden on hospitals. The debate needs to lift beyond the crude tactics of squeezing GP businesses and get serious about reforming the health system to deliver cost-effective outcomes.