Mike Moynihan and Bob Birrell from the Australian Population Research Institute have released a new report entitled “Why the public cost of GP services is rising fast”, which pins much of the blame for soaring Medicare costs on a blow-out in the number of doctors, which has easily out-paced growth in the population.

This massive oversupply of doctors is being made much worse by a conga-line of overseas trained doctors (OTDs) that enter Australia to work in a regional area only to then move to the already-oversupplied city once their mandatory term is up.

The below extracts explain what has happened.

Since 2004, successive Australian governments, ignoring advice at the time from the Australian Medical Workforce Advisory Committee (AMWAC),2 have taken as their policy starting point that there is a shortage of GPs. These governments have responded by increasing domestic medical training and facilitating an open program of OTD recruitment. Despite mounting evidence to the contrary, belief in ‘doctor shortage’ has developed a life of its own…

The number of GPs per 100,000 people in Australia far exceeds international benchmarks, especially in Anglophone countries. According to independent Australian assessments, by 2005 on this metric, there were already more GPs than was consistent with good medicine. Since then, as the following tables show, the number of GPs per 100,000 has increased sharply in metropolitan areas and even more so in some regional areas…

Given present policy settings, this oversupply will get much worse as many of the OTDs required to serve in undersupplied areas finish their service commitment and move into already oversupplied metropolitan or regional areas. Then to fill the gaps created by their departure, their employers recruit yet more OTDs to replace them. There will also be a flood of new Australian Trained doctors (ATDs) into the GP workforce. They can practise where they please which, if past experience is a guide, will mainly be in metropolitan areas…

As is shown in Table 2, which tracks the statistical record over a longer time period, the number of GPs per 100,000 and bulk-billing rates bottomed out in 2003. This outcome was a consequence of policies carefully designed to limit the number of GPs during the 1990s. This advice was based on the AMWAC and AIHW studies referred to above. By the early 2000s, these consequences had prompted a public outcry as bulk-billing rates declined and regional and outer metropolitan areas struggled to recruit GPs. The then Coalition Government, and governments since, responded by increasing the number of medical school places and by facilitating the recruitment of OTDs.

As shown above, the number of doctors in Australia rose by 47% in the decade to 2014-15, around 2.5 times the 19% growth in the overall population.

Moreover, much of this growth has come from OTDs, whose numbers have ballooned-out by a whopping 111% over this period. Most of these doctors are also practicing in over-supplied metropolitan areas, not areas of shortage:

The purpose of the OTD promotion policy was to get more doctors into underserviced areas, particularly RA 2-5 areas. But Tables 4 and 5 show that most of the extra OTDs, by 2014-15, were practising in RA 1 areas.5 Of the total increase in OTDs (6,946) shown in Table 3, 4,520 were practising in RA 1 areas and 2,426 in RA 2-5 areas.

What has happened is that there has been a gradual leaching of OTDs into RA 1 areas where there is an ample supply of doctors, as well as into the more attractive provincial cities such as Ballarat, Bendigo and Shepparton in Victoria, where the situation is similar…

Alarmingly, the report notes that OTDs are not only responsible for much of the doctor oversupply, but also the blow-out in Medicare rebates:

The OTDs influx is therefore responsible for most of the growing oversupply of GPs in RA 1 locations. They are also responsible for most of the increase in Medicare service costs. By June 2015, for all of Australia, OTDs made up 39.7 per cent of the workforce but received 49.8 per cent of total rebates. In RA 1 areas they made up 38.1 per cent of the total workforce and received 47.6 per cent of services paid for by Medicare.

And the situation is only likely to get worse:

[OTD] numbers have been rising at up to 17.2 per cent per annum since 2010. Some 53 per cent of these OTDs were located in RA 1 locations and the rest in RA 2-5 locations…

There are no rules stopping OTDs who jump the stipulated hurdles from moving, no matter how oversupplied their chosen location is. The second is that most GPs of whatever background prefer to locate in the big cities because of family preferences, proximity to top schools for kids, opportunities for research and the desire to be near family and ethnic community in the case of many OTDs.

Third, and very importantly, there are still lucrative jobs being offered. This is particularly the case for corporate practices. More of these are starting up because corporates with big money backing are in the best position to invest in new clinics. Corporates have been offering highly lucrative contracts on the condition that those employed accept their style of medicine. This is high throughput and depends on the availability of bulk billing. It is notable that advertisements for such contracts dropped off in the brief period that the Coalition Government was proposing a copayment. After this proposal was abandoned, advertisements for staff again proliferated…

There is no end in sight. With supply well ahead of population expansion, the competition for patients is set to get worse. In the case of the recruitment of OTDs, the Government has taken no notice of the GP oversupply. It continues to allow employers to sponsor new OTDs to DWS locations. So, when OTDs leave, many are being replaced. In 2014-15 there were 1,132 OTD GPs sponsored on 457 visas and in the first six months of 2015-16, another 582. Also, the Australian Government has left GPs on the Skilled Occupation List of occupations that are eligible under the permanent-entry skilled migration program. Hundreds of OTDs are being granted such visas for service in DWS and hospitals each year. Again, once they have completed their service requirements, they can practise where they please.

For those wondering why, with so many GPs already in Australia, some employers continue to sponsor more, it is partly because of the vacancies created as OTDs move out of DWS and partly because GPs employed on 457 visas are central to their business model. Those on 457 visas have to serve in the practices they are sponsored to and, as a result, can be paid very much less than ATDs or OTDs who do not have to practise in DWS locations…

The consequences of which are a continued blow-out in bulk-billed GP visits and Medicare funding costs:

As noted, by international standards the ratio of doctors to Australia’s population is already high. And, as documented, it is on course to get higher. This is the main reason why the share of GP consultations that are bulk-billed has increased from 68 per cent in 2003 to 84 per cent in 2014.10 It is also the main reason why, as Table 2 shows, the number of services per patient has steadily increased across Australia since 2003.

It could be argued that, with more GPs available, more patients have availed themselves of their services with resulting better health outcomes. A more likely interpretation of the extra services provided is that, because of competition for patients, GPs have managed their practices so as to ensure that they reach a target income level.

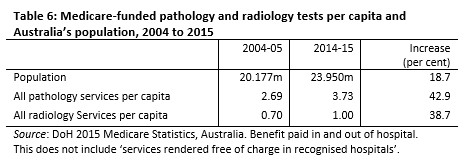

They are in a good position to do so because the almost universal availability of bulk-billing means that patients do not have to dip into their pockets. GPs can, for example, engineer extra services by recommending various tests for possible illnesses, and then prompt patients to return to discuss them. For corporate practices, where the GPs engaged are encouraged or even expected to deliver an identified income stream, such ‘management’ practices are highly likely to be utilised. Table 6 shows how Medicare funded tests per capita have risen over the past ten years.

A situation where GPs have to chase patients is not conducive to good medicine. GPs need assurance of a reasonable patient load in order to exercise discipline over patient expectations for medication and maintain professional standards. If GPs could be induced to serve where they were needed, this would encourage better medicine and slow the growth in GP costs to the taxpayer.

This will mean, as a minimum, cutting back on OTD recruitment and no further expansion in domestic medical training for the immediate future. (Alternative models of delivering GP services also need to be considered.) The government should also refuse to grant provider numbers to GPs (whether OTDs or ATDs) where the locations are already manifestly oversupplied. It would not amount to conscripting GPs to serve where they are needed. Rather, it would simply inhibit them from locating where they are not needed. As indicated, the Australian government already does this for newly arrived OTDs. They have to serve in DWS locations.

Yet another 457 visa rort rears its ugly head.