ASIC has the powers of a royal commission and, in fact, it has greater powers than a royal commission. – Treasurer Scott Morrison, speaking to reporters, April 8, 2016.

Opposition Leader Bill Shorten has promised to set up a royal commission into misconduct in the banking and financial services industry if elected.

Treasurer Scott Morrison has said that Australia’s banking system is already well regulated and that the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) has all the powers of a royal commission and more.

Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen said that a royal commission has a far broader reach than ASIC.

Who is right?

The answer is: it’s complicated. It depends on what it is you hope to achieve.

What the government said

The government and the opposition have been trading media releases on this issue.

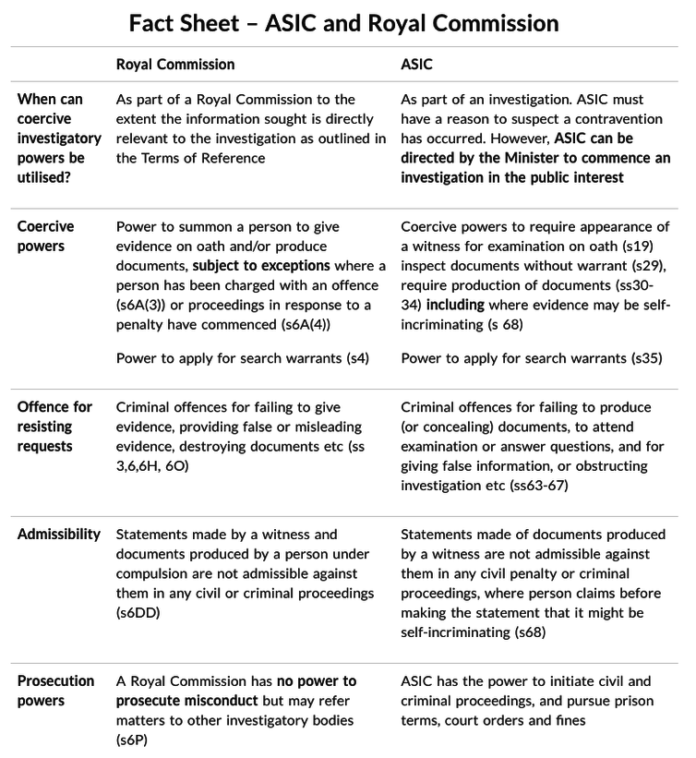

A press release issued by Morrison outlined the relative powers of a royal commission, and ASIC. It is reproduced below:

In addition to the above, ASIC can impose penalties, liability to pay compensation and management banning orders.

It is true ASIC does have very broad powers, but investigations typically centre around a specific suspected breach of the law.

If the aim is to investigate the banking industry as a whole – issues like ethics, culture and whether regulators have done a good job – then a royal commission would have broader scope to do this.

However, unlike ASIC, a royal commission cannot initiate civil, civil penalty or criminal proceedings. It must instead refer instances of suspected wrongdoing to relevant regulatory bodies, such as ASIC and the Director of Public Prosecutions.

What the opposition said

Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen has said a royal commission could go further than ASIC. In a press release, he said:

A royal commission has the power to hold public and private hearings, to use search warrants, to compel the production of documents and to call witnesses from a wider pool than an individual investigation of the kind ASIC normally runs.

Critically, the royal commission will be set up to examine the entire system, including the broader context and causes of individual cases of misconduct and how these systemic issues can be addressed.

The royal commission will also examine whether Australia’s regulators are equipped to identify and prevent illegal and unethical behaviour, especially important in the context of the Liberals’ A$120 million cuts to ASIC. Clearly, ASIC cannot examine their own capacity in the way a royal commission can.

What Bowen is describing here is a much wider look at banking than ASIC would normally take.

A royal commission’s terms of reference are set by the government and can be as broad or as narrow as the government wishes. A royal commission might investigate how a particular catastrophic event occurred – such as the collapse of HIH. A royal commission might also be set up to investigate broader, systemic problems such as institutional child abuse.

The Royal Commissions Act gives royal commissions strong coercive powers, including the power to summon witnesses to give evidence under oath, compel the production of documents and apply for a search warrant.

What can ASIC do?

ASIC’s main role is to monitor compliance with a range of corporate and financial laws. There are two ways ASIC might look into the performance of banks.

First, ASIC can conduct an investigation either on its own initiative or following a direction from the minister. An investigation can only relate to certain matters specified in the ASIC Act – mainly isolated instances of suspected illegal activity or a need to monitor compliance with the law. An investigation must be conducted in private.

Alternatively, ASIC can conduct a hearing, which can be either public or private depending on the circumstances. The hearing has to be “for the purposes of the performance or exercise of any of ASIC’s functions or powers”.

Again, it’s not a blank cheque to review the performance of an industry, and in practice seems to be used for individual cases such as licensing matters, or disqualifying directors. The minister is not able to direct ASIC to conduct a hearing.

For both an investigation and a hearing, ASIC can require witnesses to attend and give evidence on oath, compel the production of documents and apply for a search warrant.

What can APRA do?

Another player in the game is the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), which regulates financial service providers like banks, superannuation funds and insurance companies.

Unlike ASIC, its activities focus on supervision of financial service providers and encouragement of good practice, rather than enforcement of rules.

However, like ASIC, it has extensive powers to require people, banks and other corporations to provide documents and information. While most of APRA’s activities focus on actual or potential failings of specific institutions, it also has a role in conducting broader assessments of the state of financial industries.

So who’s right?

A lot of this is bickering about technical details. Both a royal commission and ASIC can require a person to give evidence, on pain of imprisonment – that’s a strong coercive power.

And it is true ASIC can prosecute and a royal commission can’t – but a royal commission can refer suspected offences to the Director of Public Prosecutions, who can prosecute them.

Morrison is correct that the Australian banking industry is regulated by bodies with significant investigative powers, including some powers that a royal commission would not have – such as the power to initiate civil and criminal proceedings on its own.

But Bowen is also correct that a royal commission could have the ability to conduct a broader inquiry than APRA and ASIC. Those bodies generally deal with individual cases rather than systemic problems.

If Labor’s position is that the regulatory system itself (as opposed to the actions of individual banks) is at fault, there are obvious limitations in giving the existing regulatory bodies the task of overhauling the system. It is a bit like asking someone to check their own homework. There has already been a significant recent Senate inquiry into ASIC’s performance, but few of its recommendations have been implemented.

In other words, the parties are talking at cross purposes.

Verdict

Both Morrison and Bowen’s specific claims about the respective powers of ASIC, APRA and a royal commission are correct. However, the central question is: power to do what?

If the aim is to investigate and prosecute specific instances of suspected breaches, ASIC is well equipped to do this on its own in a way that a royal commission could not.

If the aim is to examine the industry and system as a whole, a royal commission would have broader scope to do this. – Anna Olijnyk

Review

This is a sound article that seeks to present a balanced view of both sides of the argument.

I would add one important point. While it is true a royal commission can refer suspected offences to the Director of Public Prosecutions who can prosecute, the evidence is that criminal prosecutions rarely result from the recommendations made by royal commissions or parliamentary inquiries.

Take, for example, the Cole Inquiry, which was set up in 2006 to investigate more than $US 200 million paid in kickbacks to Iraq in contravention of the UN Oil-for-Food Program by the now defunct government-owned corporation, the Australian Wheat Board (AWB).

That particular royal commission found that there were circumstances which could give rise to criminal proceedings against AWB and various people – but no criminal action was ever pursued.

ASIC only instituted civil penalty proceedings against six former directors and officers of AWB relating to directors’ duties.

Similarly, a Special Commission of Inquiry relating to the James Hardie asbestos scandal recommended that criminal proceedings be brought against certain people. However, ASIC and the Director of Public Prosecutions did not take any criminal action and launched only civil penalty proceedings. – Vicky Comino

Anna Olijnyk does not work for, consult, directly own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above. Her superannuation fund does invest in several banks.

Vicky Comino does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.