Private health insurer Medibank has its finger on the pulse in chronic care. It sent out a letter (right, click to enlarge) to GPs a month ago to let them know about CareComplete, its new set of programs for patients living with chronic conditions. It had well signalled its interest but the letter was nicely poised for last week’s announcement of the Federal Government’s Healthier Medicare package which will trial patient centred medical homes for 65,000 chronically ill Australians from July 2017. It has a strong recruiting push underway and is not alone in its interest.

As GP Tim Senior explores in this post, there’s much to recommend the Health Care Homes, or Medical Homes model of care as they’re more widely known. But he says the role of Medibank and focus on private health insurance in the Primary Health Care Advisory Group‘s report on chronic care raises many questions, particularly around equity of access and funding models.

So too did Twitter last week…

***

Tim Senior writes:

I’ve worried in these pages before about private health insurance getting involved in primary care. While the steps I outlined then haven’t quite turned out as I predicted, the pieces are being lined up quite nicely for private health insurers to get involved.

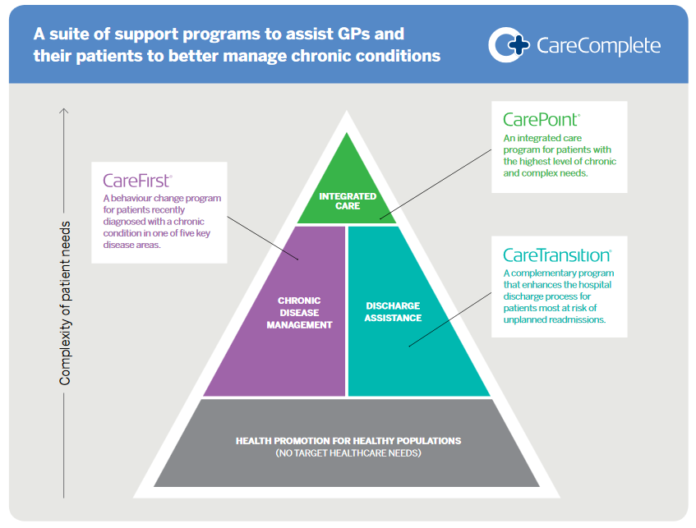

Last month some GPs receive letters from Medibank about taking part in a set of programs to better manage chronic disease and keep people out of hospital, called CareComplete.

Last week the Primary Health Care Advisory Group releases its report suggesting we move to a system closer to the medical home model to better manage chronic disease and keep people out of hospital. In immediate response, the Federal Government announces the trial of Health Care Homes’ for complex and chronically ill patients.

Now, it should be said that there are some very good things going on here. The Medical Home – or, to give it its proper name, the patient-centred medical home – is the correct model to draw on to improve primary care. While evidence can be difficult to compile for something as complex as primary health care provision, the indications are that it is an effective model. The RACGP, among others, have been advocating for a medical home model for a while now, and Health Minister Sussan Ley is right to suggest that doctors have been calling for this. However, the devil is in the detail, and a medical home model doesn’t suddenly mean you can spend less on health. The financial and economic benefits come from healthier people able to work, and fewer hospital admissions, freeing up capacity.

There were two important things that were notable in the PHAG report. First, Key Recommendation 6 is all about Private Health Insurance in chronic disease management, including development of their role in the community.

Second, there is no mention of health equity. There is a sidelong mention in recommendation 11, that patients should contribute to their health care costs ‘where they are able’, which presumably means contribute again at the point of care, in addition to taxes and Medicare Levy.

But amidst all the talk of chronic disease, multimorbidity and ‘risk stratification’, nowhere is this made explicit that this must take account of social gradients in health. We know that chronic diseases are more common in the less well off and we know that multimorbidity comes in at a younger age the less well off you are. If our ‘risk stratification’ doesn’t take this into account, or that there are fewer GPs in the most deprived areas seeing patients more frequently, then we won’t succeed for those who have the most to gain.

Enter Medibank. After realising that just enhancing access to GPs for their members didn’t really work, they’ve embarked on CareComplete, a program designed to keep people with chronic diseases out of hospital. The only information I have on it is from their promotional brochure, but it makes interesting reading.

Care Complete is made up of three programs: CarePoint, for those with the most complex needs, CareFirst, ‘a behaviour change’ program for those with some chronic diseases, and CareTransition, to help discharge from hospital.

The program is pretty well designed, and is based on relevant evidence. I imagine it will work well for many patients – the sort of patients included in the case studies, in fact. They all look like middle-class white people who have agency and control in their lives, and just need a bit of information and guidance.

Once again, what isn’t mentioned is instructive. There’s no mention of mental health, even as one of the chronic conditions. That’s a huge gap. The guidance is all based around the health system, but many of my patients need similar guidance around housing, Centrelink, legal services, or employment agencies if they are to tackle their health problems.

Most interestingly is that the program is open to everyone – in theory. Patients are identified by their GPs, and must be funded by someone. Medibank suggest it might be ‘government, PHN or a health fund’. That’s a good move, as it means this is potentially not limited to those with private health insurance. I can well imagine PHNs funding a program like this for their patients, or even state health systems, as an attempt to keep people out of their (very costly) hospitals.

I think many state health systems will be quite drawn to this model, as they will see opportunities to save money from keeping people out of hospital. PHNs will save less, but it may help meet some of their KPIs. Some GPs will like the idea, and some may be more wary, seeing it as leading towards a system of managed care and capitation, not something that’s apparent from the current brochure. Patients who are in the system will appreciate it, but those who are not are at risk of getting left behind.

However, the program raises some important questions for the health system. As Barbara Starfield showed “…care must be person focused rather than disease or procedure focused,” (a phrase that should be tattooed on everyone involved in health care policy). The eligibility by physical medical condition isn’t this.

One of the case studies proudly points out how an occupational therapy (OT) assessment was arranged urgently, jumping a queue for that service. The funding issues are frequently fudged – the ‘Allied Health services (five per annum)” available in CarePoint are the same number as those under Medicare, which makes me think this is a system paying for co-ordination of the care already available through Medicare (which, to be fair, is exactly how other systems have worked in the past, both commercially and through Medicare Locals). In one case study, community services fund OT appliances, which would presumably be available for everyone regardless of this program. To roll out a system like that, we have a complex public health system that we pay a private provider to help navigate.

Fundamentally though, could a service like this be available to everyone who needs it? It would need to be, if it was going to make a difference. This may not be a problem. We already provide public money to private health providers to provide a public service. Many of these are GP-owned small businesses, some are shareholder-owned private companies which need to make a profit (and Sussan Ley has had comments to make on this for pathology companies). This may not be a bad thing, provided everyone gets covered. It may well be a better spend of health money than the private health insurance rebate. However, it’s just never been discussed. Will there be a range of providers competing with Medibank for these services? Will we see competitive tendering between providers? How will we avoid cherry picking the easier (and so more profitable) groups, leaving those who could most benefit at the back of the queue again? And that doesn’t even begin to consider issues of clinical governance or how to ensure cultural safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

If there’s one take home lesson it’s this: we know that if we don’t aim for equity in our policies, and then listen to those who most need our services, we make our health gaps worse.

Dr Tim Senior is a GP who works in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, and a member of the Croakey Connective! You can follow him on Twitter at @timsenior.