Inside the hunt for a Zika virus vaccine

With the Zika virus outbreak sweeping across Central and South America and knocking on America’s door, the race is on to find a vaccine.

Recently, officials at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that a potential Zika vaccine could make it to human trials by the end of the summer, one of the fastest timelines proposed for such a vaccine yet.

Meanwhile, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than a dozen other research groups around the world are also working on developing a vaccine — a cause that’s grown more urgent as concerns about the virus’s health effects, such as microcephaly and a separate nerve disorder, continue to increase.

Dr Chan: Growing evidence of a link w/ Guillain-Barré synd expands the group at risk of complications well beyond women of child-bearing age

— WHO (@WHO) March 8, 2016

Who will be successful first — and how long it will take — remains to be seen. But researchers say they have a jump start on the Zika vaccine that could pave the road for faster results when compared to other vaccine efforts that have taken many years.

How the past informs the present

Scientists are quick to admit that we still have much to learn about the ways Zika affects the human body, and it may seem as though our uncertainty on this front would inhibit our ability to develop an effective vaccine.

But that’s actually not the case, according to Anthony Fauci, director of the NIH’s National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

“One is understanding the disease — one is preventing the disease,” he said, in an interview with Mashable.

It’s possible to come up with an effective vaccine for a virus whose effects we don’t fully understand, as long as know what kind of virus it is and how the virus is physically structured and goes about infecting its host.

Traveling for #springbreak? See CDC travel notices for important #Zika information: https://t.co/x6LZwViIJy pic.twitter.com/vg0BZrqdXl

— CDC (@CDCgov) March 9, 2016

And when it comes to Zika, we already have a leg up in the form of previous vaccine research on related viruses.

Zika is what’s known as a flavivirus. This is a family of viruses primarily found in ticks and mosquitoes, but that are frequently able to infect humans as well.

Well-known examples include dengue fever, yellow fever, West Nile virus and Chikungunya — all of which, incidentally, can be carried by the same Aedes aegypti mosquito that helps to transmit Zika.

All flaviviruses have similar physical structures — they consist of single-stranded RNA surrounded by a kind of protein shell.

Flavivirus outbreaks have been common in recent decades, so there’s already been plenty of work done on developing vaccines.

“We’ve been successful in the development of vaccines for certain of the flaviviruses, such as yellow fever, such as dengue,” Fauci said.

Most recently, an NIH-developed dengue vaccine was approved to enter phase three trials in Brazil, which involves testing among large groups of hundreds or thousands of humans.

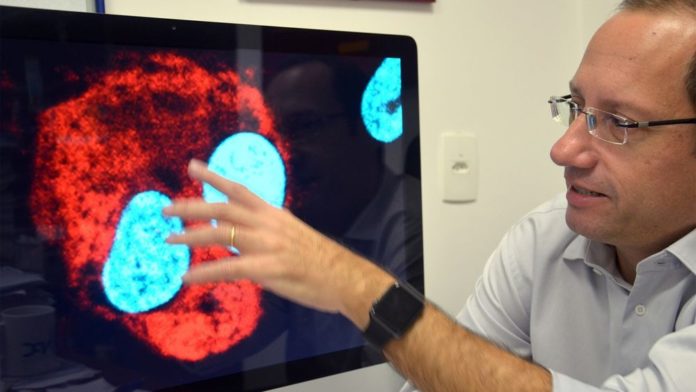

Researcher Stevens Rehen from the Instituto D·Or using a microscope image to explain how the Zika virus (RED) can attack human neurons (BLUE) in his office in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, March 9, 2016.

Image: Georg Ismar/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

Previous work on these flavivirus vaccines is now being used as a kind of “background” for Zika vaccine research, Fauci said. Researchers are now applying some of the same techniques used in the previous vaccine development to the Zika research.

Multiple approaches, one goal

The NIH’s current front-runner for a Zika vaccine candidate builds on an approach previously used for West Nile.

“With the West Nile vaccine, we used what’s called the DNA approach,” Fauci said. This technique involves inserting genetic material from the West Nile virus into a plasmid, which is a kind of small, ring-shaped strand of DNA.

“When you’re dealing with an emergent situation and you’re in the middle of an outbreak, it becomes much more easy to test whether or not [a vaccine] works”

When injected into humans, these plasmids can replicate and produce virus-like particles, which don’t actually produce the effects of the real virus, but nonetheless trigger an immune response in the host.

The NIH’s West Nile vaccine was shown to be effective, but did not move forward commercially when the NIH was unable to find a pharmaceutical company to partner with on advanced development.

Nevertheless, the technique is now proving fruitful with the NIH’s Zika work, Fauci says.

“We’re taking that same platform…and instead of sticking a gene for West Nile in there, we’re sticking a gene for Zika,” he said.

The researchers are hoping to be able to begin conducting phase one human trials around the end of August or beginning of September.

In the meantime, the researchers are looking into other approaches as well. Their second technique builds on the dengue vaccine, which is what’s known as a live attenuated virus vaccine.

Countries and territories with active transmission of the Zika virus.

Image: CDC

The more traditional live attenuated vaccines contain a weakened version of the actual virus. So while they don’t cause harmful effects in the body, they typically induce a strong immune response.

“We’re going to make a hybrid of the already existing dengue live attenuated virus vaccine, and we’re gonna add onto it a component of Zika,” Fauci said of his team’s research on that front.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, researchers at Indian biotechnology company Bharat Biotech are working on their own Zika vaccines using different techniques. The most advanced of their developments is what’s known as an inactivated vaccine. This approach essentially introduces a “dead” virus to the host — it’s unable to replicate itself or cause any harm, but the body still recognizes it and launches an immune response.

At a press conference on Thursday, the NIH’s Fauci said that it would be ideal to ultimately produce several types of vaccines, both using the live virus and the inactive virus, for use on different populations.

A live attenuated vaccine could be risky for use in pregnant women, for example, so using a “dead” or inactivated vaccine would be best for at-risk women who are already pregnant.

But live attenuated vaccines have generally been shown to be so effective that it would be ideal to produce one to use for people who are not pregnant — especially if they may become pregnant in the future, he said.

Growing fears over Zika’s effects

Increasing confidence in Zika’s ties to serious health consequences are largely driving the vaccine fervor. While the virus’s immediate effects are fairly mild — the most common symptoms include fever, rash and joint pain, all of which usually dissipate within days — it’s feared to be associated with two rare and potentially devastating health conditions.

The first of these is microcephaly, a condition in which the babies of infected mothers-to-be are born with undersized heads and underdeveloped brains. The condition has been linked with lifelong neurological impairment and developmental delays, as well as death.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), testifies about the Zika virus in Washington, D.C., on February 24, 2016.

Image: saul loeb/AFP/Getty Images

While the link between Zika and microcephaly has not been definitively established, scientists have a high degree of confidence that it exists.

In fact, a study just published March 4 in the journal Cell Stem Cell further strengthened the case for the microcephaly connection by demonstrating that the Zika virus can infect and stunt the growth of certain cells required for a fetus’s brain development.

The other condition now feared to be associated with Zika is Guillain-Barré syndrome, or GBS, an illness that causes a person’s own immune system to attack their nerve cells, resulting in muscle weakness or even paralysis.

Its causes are not fully understood, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention points out that many people with GBS reported a bacterial or viral infection before they were diagnosed with the condition. Now, health officials are saying that an increasing number of people infected with Zika are also coming down with GBS, suggesting that there may be a link between the two.

A recent paper, published last week in The Lancet, also lends support for this connection, describing a 2013-2014 Zika outbreak in French Polynesia. Doctors in that case examined patients who were diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome and found that more than 90 percent of them had Zika antibodies in their blood.

An uncertain outlook

At a Feb. 12, press conference, the WHO’s assistant director general for health systems and innovation, Marie-Paule Kieny, said that at least 15 companies or groups around the world are currently engaged in the quest for a Zika vaccine.

But for the time being, she said the two front-runners are the NIH’s DNA vaccine and Bharat Biotech’s inactivated vaccine.

She added, “In spite of this encouraging landscape, vaccines are at least 18 months away from large-scale trials.” This was just an estimate, and the NIH is optimistically shooting for human trials by the end of the summer — but when a vaccine might actually become commercially available is another story and depends on a variety of factors.

For its part, Bharat Biotech has reportedly cautioned that its vaccine could take 10 years to hit the market, depending on the types of regulatory hurdles it runs into while conducting trials and filing for approval.

Marie-Paule Kieny, Assistant Director-General, Health Systems and Innovation, of the World Health Organization speaks during a press conference in Geneva, Switzerland, on Friday, Feb. 12, 2016.

Image: Martial Trezzini/Keystone via AP.

The NIH’s Fauci was more optimistic, saying three to five years might be a more realistic timeline for a “vaccine that has all of the i’s dotted and the t’s crossed, approved by the FDA.”

However, he noted that the success of clinical trials on a Zika vaccine will likely depend on the way the current disease outbreak progresses in the near future.

“When you’re dealing with an emergent situation and you’re in the middle of an outbreak, it becomes much more easy to test whether or not [a vaccine] works,” he said. With so many infected people potentially able to participate in a large-scale trial, tests that might normally take up to five years could proceed faster.

He said his research team is hoping to start a phase one trial by September and finish by January of 2017, although this is just a hypothetical scenario for now.

If this plan were to succeed, and the outbreak were still in full swing at that time, a phase two trial “may be able to show efficacy as early as eight to 10 months after you start,” he said.

A warning on funding

The White House has requested $1.9 billion in new spending for Zika-related research, which would help pay for vaccine research, but Congress has not approved it yet.

In a press conference on Thursday, Fauci said if the funding is not approved, it could spell problems for the ongoing vaccine research.

“We’ve already started down the road of making the product for this first vaccine candidate by moving money out of other important areas into this area,” Fauci said, adding that this is not a viable long-term solution to the funding problem.

“If we don’t get that money, we may find ourselves halfway through a phase one trial and not being able to finish it and take that next immediate step into the larger trial,” he said.

The WHO’s Kieny also expressed uncertainty about the vaccine timeline uncertainty during the February press briefing.

“For Zika…it is not impossible that you will have a large epidemic wave, and behind that for a few years much less disease,” she noted.

“So we have to see how this develops and how easy it will be to test for efficacy. It depends on how much disease will be prevalent at that moment.”

In other words, it’s possible the Zika outbreak will end before a vaccine is developed.