Nearly 35 years have passed since the first reports of deaths from a mysterious illness were finally attributed to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

During that time, researchers, clinicians, activists and public health professionals have worked hard to decrease the soaring rates of deaths and infections but health experts no longer speak of a cure as a viable goal.

Only one of the approximately 80 million people infected since 1981 is considered truly cured, said Professor Sharon Lewin, director of the Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity.

Timothy Ray Brown, also known as the Berlin patient, has no HIV in his body after he received a stem cell transplant for leukaemia in 2007 from a person naturally immune to HIV.

Combination antiretroviral therapies revolutionised treatment of HIV from 1995 and today, people on effective daily treatment can have close to a natural lifespan.

Although most people who take antiretroviral therapies have very low or undetectable levels of HIV in their blood, they are not cured and must maintain daily treatment for life.

Ninety-nine per cent of people who stop their treatment will have the virus in their blood two to three weeks later, Professor Lewin said.

With a cure unattainable, it “might be more achievable” to focus on remission.

Previously called a “functional cure”, remission occurs when someone stops their treatment and the levels of virus in the blood remain controlled at very low or undetectable levels.

“We’re way off that at the moment,” Professor Lewin said.

“Over the past few years there have been increasing reports that remission is possible. It’s not impossible.”

Shock and kill approach: hunting down a hidden virus

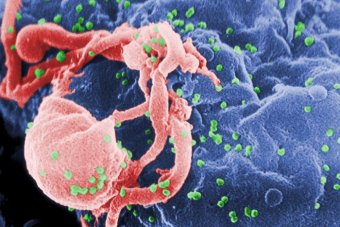

Researchers know that HIV can hide in the body early in infection and can integrate into the genome of human cells, including in the immune cells [CD4 positive T cells] that HIV infects.

Professor Lewin said HIV also hides in the body during antiretroviral therapy.

“When people are on treatment … you can’t find the virus in the blood but if you look inside certain cells, it’s always there. It just goes into shutdown mode or it goes into hiding. Many viruses do this. They have an active form and a resting form where the virus sits dormant. But it can wake up at any time,” she said.

One of the newer treatment strategies to flush the virus out of hiding is the so-called “shock and kill” approach.

“Shock and kill is a way of coaxing the virus out of the latent form so it becomes visible to the immune system and then the cell is destroyed. Or sometimes when a virus comes out of a cell, it can then self destruct,” Professor Lewin said.

Recently there have been reports of new drugs that can quite effectively shock the virus, she said.

“But at the moment none of the studies have yet showed that that alone will kill the cell. Those studies are now happening to combine a shock with something that will then kill the cell,” Professor Lewin said.

Professor Lewin’s group has just reported in The Lancet HIV that a drug used for alcoholism, disulfiram, can wake up a dormant virus and is safe to use.

Gene editing: eliminating a home for HIV

Another experimental treatment is the breakthrough technology of gene editing.

The technique involved removing and treating blood cells with gene scissors or gene editing compounds that eliminated the receptor for HIV, a molecule called CCR5, which is an important protein for the virus.

The modified blood cells are then put back in the patient.

Professor Lewin said the study showed the technique was safe, but the virus returned when patients in the trial interrupted their treatment.

While the use of this technology is “interesting science”, she said it was unclear whether such a high-cost and complex technique would help the 80 per cent of people living with HIV in low and middle-income countries.

Professor Sean Emery from the Kirby Institute in Sydney agreed.

“I don’t think that there’s any hope whatsoever that the current stable of experimental approaches toward inducing remission of cure have any feasible hope of being a component of treating HIV in southern Africa or the Indian subcontinent or South-East Asia or Russia or anywhere,” Professor Emery said.

“That doesn’t mean that it’s not a perfectly reasonable research agenda, of course it is, but it shouldn’t be couched in terms of it being a panacea for how we remove HIV infection from a public health issue globally.”

Zero new infections, zero discrimination, zero deaths

In the meantime, UNAIDS has just released a global strategy to combine a range of treatment and public health approaches to achieve zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero deaths by 2030.

While Australia is “pretty close” to achieving global treatment and diagnosis targets, Professor Lewin said preventive treatment such as pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP for people at significant risk of acquiring an HIV infection, would help to reduce the infection rate, which has plateaued at about 1,000 new infections per year.

She also said Australia needed to make testing easier.

“There’s a small gap here of people who are infected and don’t know they’re positive and by increasing testing we can make sure that we can close that gap,” she said.

Professor Emery was one of the leaders of the START trial.

“What the START trial resolved was that it is indeed beneficial to individuals with HIV infection that their treatment commences as soon as possible after diagnosis of the infection,” Professor Emery said.

“We’d known for quite some time that on a population basis, if you gave people treatment, their propensity to transmit the virus [to others] is substantially reduced.

“So treatment with antiretrovirals is very good for individuals and it’s very good for the populations and communities in which those individuals are found.”

Professor Emery said a true step forward on a global scale would come from development of an affordable preventive vaccine that could be also used in countries with lower income.

“Vaccines are the Holy Grail for HIV. It’s very clear that a public health vaccine for prevention would represent a massive improvement in our ability to control the onward transmission of the estimated two million new infections that occur every year,” he said.

“Vaccine research is really something that needs to be re-energised and grown as an enterprise in the research setting because truly effective public health vaccine for HIV would represent an enormous improvement.”