IT was hailed as the “breakthrough” in treating those suffering with debilitating Parkinson’s disease but instead it left a trail of death, heartache and destruction.

Queensland mum Julie Bury attempted suicide and experienced a radical personality change after doctors implanted electrodes in her brain to control her Parkinson’s disease.

Ms Bury had Deep Brain Stimulation surgery in March 2013, again in August 2014 and then tried to kill herself in February.

“My tremor was worse than before. I’d become very compulsive and impulsive,” she said.

“I’d gone from being a conservative mother who wore black and hated loud music to wearing orange and listening to loud music.

“I party. I’m reckless. I don’t know myself.”

NSW dental prosthetist Kenneth Mawby took his own life after the same surgery made him impulsive and paranoid.

He became totally manic, smashing his car twice and not sleeping for six weeks.

His widow Cherie said the surgery that was meant to give him a better quality of life ended up costing it.

The day he killed himself Mr Mawby told her: “I’m never going to be better, this is worse than before.”

The treatment involves opening the skull to insert electrodes in the brain with a remote battery-powered device like a pacemaker which allows the electrodes to be turned on or off.

However patients can develop rage, hypersexuality, they self harm and feel estranged from themselves, studies have found.

The $125,000 surgery was hailed a breakthrough in treating the disease which affects walking, writing, speech and motor skills but patients aren’t being warned of the deadly side effects.

A 2008 study published in the journal Brain found 24 of 5311 deep brain surgery patients committed suicide and a further 48 attempted suicide — 13 more deaths than in the general population.

“Suicide is thus one of the most important potentially preventable risks for mortality following subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s,” the study concluded.

“Post-operative depression should be carefully assessed and treated.”

When Mr Mawby developed problems after his surgery, his family could not get an appointment with his doctor Professor Peter Silburn for four weeks.

They say they were given no instructions on how to change the settings on his brain electrodes.

They had to rely on a neurologist who was new to deep brain stimulation but Mr Mawby still got no relief from his distress.

The NSW deputy Coroner has issued a scathing indictment of neurologist Prof Silburn, who is a key proponent of the surgery, describing his conduct as “dishonourable” and referring him to the Queensland Health Ombudsman.

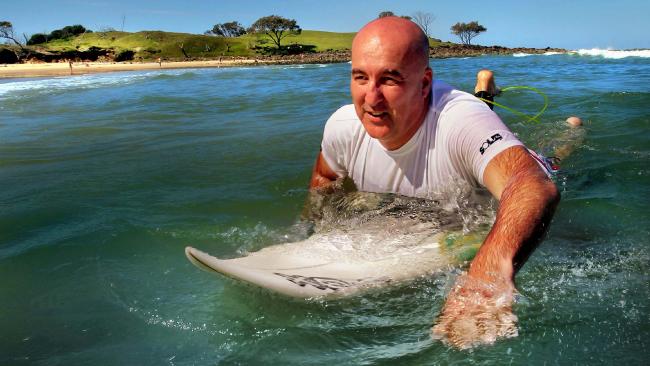

The leading surgeon was awarded an Order of Australia for his work in 2013 and has been the subject of glowing TV and newspaper reports, with many patients thrilled at how his surgery has changed their lives.

Last week he was elected vice president of Parkinson’s Queensland.

He said: “Patient privacy prevents me from disclosing other factors in this particular case but of course my condolences go out to the grieving family.”

Professor Simon Lewis, of the University of Sydney, said patients need close monitoring immediately after surgery “because there is a risk of personality change”.

“It can be devastating. It happens so quickly and can include suicidal behaviour through to gambling,” he said.

However, he said the problem can be made better by carefully changing the position where the electrodes stimulate the brain using the control device.