Pigeons can be trained to spot cancerous breast tissue, a new study has found.

While they will not be replacing doctors any time soon, the birds are able to distinguish between cancerous breast tissue and benign tissue, researchers from the University of Iowa and the University of California have found.

The study was conducted to provide understanding into how physicians developed medically essential visual skills for diagnosis, and how they processed visual cues.

Pigeons were chosen as their visual system properties are very similar to humans.

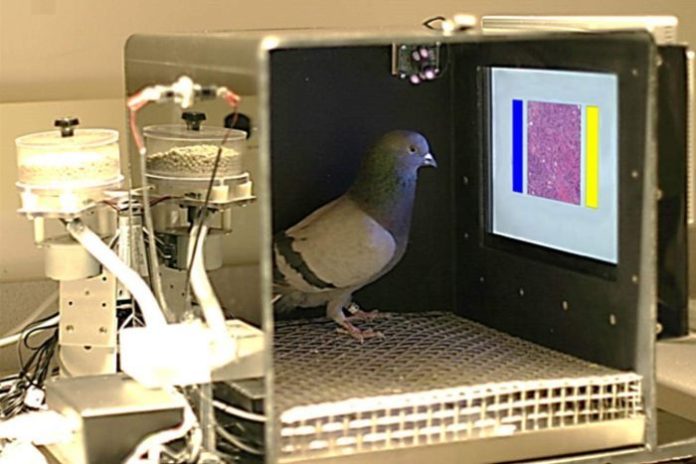

Training with food reinforcement was used to teach the birds to differentiate between benign and malignant breast tissue using a set of touch screen slides.

When new slides were introduced, the pigeons were found to be able to generalise what they had learned from the original slides and apply the knowledge successfully.

While the birds’ accuracy was slightly affected when there was no colour or when the image was compressed differently, the study noted this could be fixed with more training.

“The birds were remarkably adept at discriminating between benign and malignant breast cancer slides at all magnifications, a task that can perplex inexperienced human observers, who typically require considerable training to attain mastery,” said the study’s lead author, Dr Richard Levenson.

“Pigeons’ accuracy from day one of training at low magnification increased from 50 per cent correct to nearly 85 per cent correct at days 13 to 15.”

For a separate mammogram study, the pigeons were trained to detect images with and without microcalcifications, and to detect the presence of malignant breast masses using a similar process.

In that test, they were found to be capable only of image memorisation and were unable to generalise successfully when shown other examples.

However, the study’s authors acknowledged that task as “very challenging” even for humans.

“The data suggests that the birds were just memorising the masses in the training set, and never learned how to key in on stellate margins and other features of the lesions that can correlate with malignancy,” Dr Levenson said.

“But, as this task reflects the difficulty even humans have, it indicates how pigeons may be faithful mimics of the strengths and weaknesses of humans in viewing medical images.”

The authors say the study’s results suggests the birds “could be used as suitable surrogates for human observers in certain medical image perception studies, thus avoiding the need to recruit, pay, and retain clinicians as subjects for relatively mundane tasks”.