The first sign something was wrong was when Stephen Taylor started getting stressed.

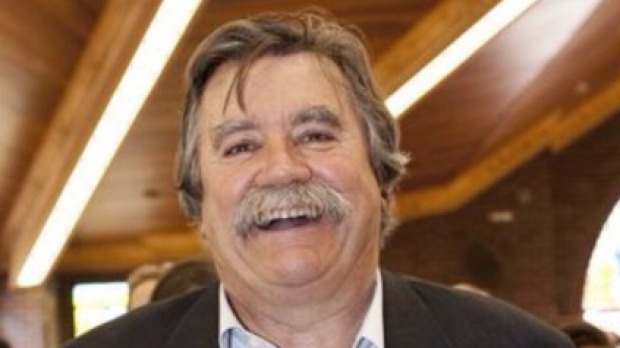

The 71-year-old retired science educator was “a pretty easy-going, laissez-faire sort of person” he says, until the tumour started to take hold.

But once the vicious glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) tumour began to grow in his brain he became hugely stressed by, and often unable to achieve, simple tasks like getting ready to leave the house.

“I began having substantially less co-ordination, and a breakdown I suppose you would call it of my zeal, or willingness for various sorts of tasks,” Mr Taylor, who was diagnosed with brain cancer in May this year, said.

Doctors estimated it had only taken between two weeks and two months for a mandarin-sized tumour to embed itself in the part of the brain that governs organisational skills.

The speed at which GBM grows, and returns after treatment, means people like Mr Taylor have no time to waste.

And now a new global trial announced in Washington DC and Australia on Friday will give patients access to cutting edge treatment and research in weeks, when in the past they may have been forced to wait up to a year.

The GBM AGILE study is the biggest global collaboration in the history of brain cancer research.

Michelle Stewart, the head of research strategy at Cure Brain Cancer Foundation, which contributed $1.2 million towards it, said it was “the best opportunity we’ve had to dramatically improve outcomes for people with brain cancer”.

Patients will be enrolled all over the world, including 300 in Australia, in an unusual trial that will test multiple treatments based on the molecular make-up of patients’ tumours, abandoning those that don’t work and replacing them with others.

“One of the big problems is that traditional trials leave patients and researchers in the dark for long periods of time,” Ms Stewart said.

“It will reveal potentially lifesaving treatments far faster.”

John Simes the director of the National Health and Medical Research Centre Clinical Trials Centre, who helped develop GBM AGILE, said it would allow treatments to be adapted in direct response to global data being collected about how patients were responding.

It would also have a team of expert doctors, scientists, government and industry that would be constantly on the look-out for promising treatments to add to the trial.

“We can assess a range of promising treatments and say ‘well this is promising but this one is actually not,” Mr Simes said.

“The idea is to maximise the chance of finding new treatments”.

But the trial would allow people more chance to participate before their condition progressed as far.

“That’s one of the things we all struggle with, when there is a trial you would like to enrol someone in but it hasn’t started yet,” he said.

The trial will start next year in Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne, with participating hospitals to be selected by the end of this year.

Mr Taylor said it was important for patients to have the opportunity to take part in such trials.

“If anything can add to the pool of research that can only be good,” he said.