How the new ‘female Viagra,’ on sale today, used feminism to get approved

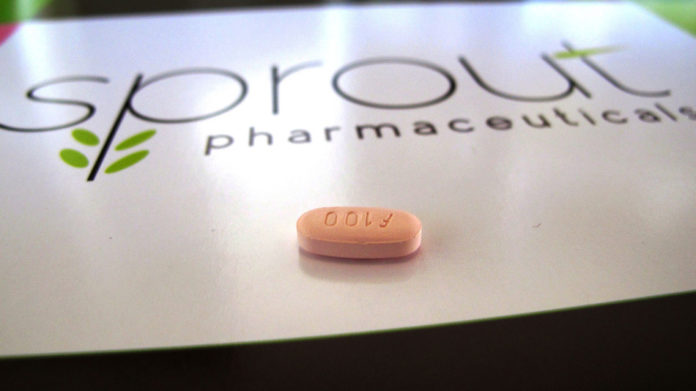

Today, October 17, a new drug will be available to fight low libido in women: Addyi, known as the “female Viagra.”

But it comes with strings attached: a history of regulatory rejections, concerns about its effectiveness, daily dosage, and potentially fearsome effects when combined with alcohol. A magic bullet, it’s not.

While Addyi has been hailed as a huge step forward in enabling and accepting women to express their sexuality by increasing the urge to have sex, it has vocal scientific critics who have decried its side effects and lack of testing on women. One major bone of contention: its safety assurances rely on a study that included only two women out of 25 patients — 6 of whom suffered “severe adverse reactions” including dizziness, low blood pressure, and passing out after taking the drug along with a lot of alcohol.

The FDA rejected Addyi twice before, in 2010 and 2013. On the third try, Sprout pursued a more aggressive campaign, signing up women’s groups to position Addyi as a healthy, feminist-approved way for women to take control of their sex lives.

Many argue the promotional push overstated the drug’s minimal effectiveness, misrepresented clinical trials to downplay side effects, unduly influenced members of Congress and otherwise flouted the theoretically science-based vetting process for drugs.

“I don’t know what else you could have had misinformation about,” says New York University sex psychologist Leonore Tiefer.

Yet Addyi succeeded, championed by a cast that included an impassioned female CEO, the male researcher who helped make Viagra happen, and numerous feminists who backed their efforts in the belief that Addyi is a victory for women. Working against them were more than 200 fiercely critical scientists who denounced the drug.

Here’s how it happened.

A blackboard in Sprout Pharmaceuticals’ Raleigh, N.C., headquarters makes an allusion to the male erectile dysfunction drug Viagra on Friday, Sept. 27, 2013. Sprout failed in its initial efforts to get Addyi approved by the FDA.

Image: Allen G. Breed/Associated Press

This drug was pro-sexual

In 1999, a German drug giant, Boehringer Ingelheim, gathered hundreds of clinically depressed men and women to test a new antidepressant.

The drug turned out to be a failure — at least in terms of its stated mission. The patients’ depression did not ease.

What the trials did uncover was something potentially more promising: a modest but noticeable boost in the number of women who reported a heightened sex drive after taking the medication every day.

The small pink pill called flibanserin, now Addyi, was more than a pleasant surprise. Boehringer Ingelheim had stumbled upon a treatment that could serve a growing number of women being diagnosed with a condition then called Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder, or HSDD. It’s a stress-inducing loss of libido without an identifiable physical or psychological cause.

“They identified something that they weren’t considering — that this drug was pro-sexual as opposed to anti-sexual,” says Irwin Goldstein, a foremost researcher in the sexual medicine field who has advocated on behalf of several sexual dysfunction drugs.

Just one year before those initial trials, Pfizer’s release of Viagra, hailed as a milestone breakthrough in treating male impotence, had proven a blockbuster success. With Viagara flying off the shelves, drug companies were already scrambling to replicate the success in a sexual dysfunction drug catered to women.

Flibanserin looked like the answer — the kind of once-in-a-lifetime hit that could make a pharmaceutical companies’ profits for decades, just as Viagra was,, but the money wasn’t theirs just yet.

What followed was more than 15 years of regulatory rejections, ownership changes, heated and divisive debates within the scientific community, and an unprecedented flood of aggressive lobbying.

When Addyi finally received approval from the FDA, in July, it shocked critics, who argue that the drug’s potentially dangerous side effects overshadow its purpose.

Yet the makers tout it as a victory against a purportedly sexist regulatory system and drug pipeline that failed to serve women’s needs the way it served men’s.

Even as Addyi becomes available, the debate continues.

From blue to pink

Irwin Goldstein, the sexual researcher, played a pivotal role in championing Viagra throughout its clinical trials. He did the same for Addyi.

The San Diego-based doctor, who works as a consultant for Sprout in addition to his own practice and role as director of sexual medicine at Alvarado Hospital, received about $120,000 in consulting, speaking and other fees from the pharmaceutical industry between August 2013 and December 2014, according to mandated disclosures.

According to health journalist Ray Moynihan, Goldstein chaired a series of conferences dedicated to female sexual dysfunction, with sponsorship from pharmaceutical companies.

At one of the conferences, doctors pinpointed HSDD and recommended treating it with medication. None of the proposed drugs worked out.

In 2004, Pfizer mothballed a research drive to prove that Viagra could work just as well for women as it did for men. That same year, the FDA struck down Procter & Gamble’s testosterone-boosting skin patch designed for women who had their sexual organs, citing a possible risk of breast cancer and heart disease. A testosterone gel for women developed by BioSante failed to perform in two big studies in 2011.

And, in 2010, importantly, Boehringer’s attempt to push flibanserin onto the market was cut short by a unanimous FDA panel vote that noted its weak effect on increasing sex drive.

Many have pointed to Goldstein’s strong ties to the pharmaceutical industry as evidence of a conflict of interest.

We asked him. Goldstein rejects the implication that those fees might motivate him to do anything not in his patients’ best interests.

“My time is valuable,” Goldstein tells Mashable. “I take good care of my patients and as a result of that some of my time should be spent helping drug companies develop products for my patients…My intentions are to help people have choices—that’s the way I work.”

Resurrecting the little pink pill

Goldstein is the person who had the single biggest role in resurrecting flibanserin, or Addyi.

Boehringer gave up after the FDA rejection in 2010. It shelved the project despite having burnt more than $1 billion in development costs — par for the course in an industry where a handful of blockbuster products fund research costs for the 95% of experimental medicines that never see the light of day.

But Goldstein had other ideas for the failed pharmaceutical.

“It seemed to be a huge shame that this drug would be shelved that way,” Goldstein said.

He tracked down Sprout chief executive Cindy Whitehead at a conference and showed her emotional videos in which his patients who had been taking the drug as part of the clinical trial cried when they heard it had been shut down.

That moment spurred Whitehead to action, she told Mashable.

With $20 million in angel investor funding, the Raleigh, North Carolina-based Sprout bought the rights to flibanserin the year after Goldstein had talked to Whitehead.

prout Pharmaceuticals CEO Cindy Whitehead works in her office in Raleigh, N.C.

Image: Allen G. Breed/Associated Press

Whitehead says her passionate embrace of flibanserin arose from the idea that women could finally have their own section of the pharmaceutical market. The pharmaceutical industry belongs to men.

“In part because of the female menstrual cycle and the risk of testing women who could be pregnant, historically drugs have been tested in men and so there’s a legitimate concern that we have better evidence in men than we do in women,” says Dr. Stacy Lindau, who treats sexual dysfunction in female cancer patients at the University of Chicago.

Women’s physiology, then, remains far less understood than that of men — which, Whitehead says, contributes to the idea that women are mysterious, emotional creatures.

“The field up until then had been ‘let’s take this drug that works for men and see if it works for women,'” Whitehead tells Mashable.

“One of my passions from the beginning is that there’s such a strong societal narrative that would reduce all things in the bedroom for men to biology and all things in the bedroom for women to psychology,” she says.

Feminist victory or industry spin job?

Flibanserin, however, initially fared no better under Sprout than it did under Boehringer.

The FDA once again struck it down in 2013, arguing that the nebulous effectiveness of the drug was not enough to justify health risks like fainting, dizziness, nausea and a possible negative interaction with alcohol.

The FDA just wasn’t convinced that flibanserin made much of a difference. According to the results submitted then, women who took the drug reported 2.5 more satisfying sexual experiences per month as compared to 1.5 for those who were given a placebo.

After two FDA rejections, most companies would have given up. Sprout – and Whitehead – pivoted their strategy, trying again to resurrect the potential moneymaker.

Sprout launched a formidable public relations campaign that sought to paint the lack of drugs treating female dysfunction as a matter of gender bias in the FDA’s judgment — a sign that the pharmaceutical industry was stacked against women.

It would turn out to be a tremendously successful appeal.

Sprout left nothing to chance in constructing the drug’s third attempt at approval, creating a campaign based not on science but on emotion. To create a feminist upswell, it funded a coalition of women’s groups called Even the Score to push for the drug’s approval. The campaign flew patients from across the country to testify at FDA advisory panel meetings.

Even the Score is a non-profit campaign backed by a coalition of 24 women’s groups including the National Council of Women’s Organizations, the Black Women’s Health Imperatives and the National Organization for Women.

Even the Score was organized last year by a paid consultant for Sprout along with multiple PR firms. It is bankrolled in part by Sprout as well as Canada’s Trimel Pharmaceuticals, which is developing a nasal testosterone spray for women with female orgasmic disorder.

Even the Score, with the power of feminist advocacy, succeeded in convincing the notoriously wary FDA — despite its two previous rejections — to approve Addyi.

To the shock of the drug’s many skeptics, the FDA’s advisory panel recommended in favor of green-lighting it, and it was approved by a vote of 18-6 in August.

Still signaling the FDA’s wariness, the approval came with a host of stipulations including an 18-month ban on radio and television ads and more extensive follow-up research.

A HUGE THANK YOU to our supporters and advocates! Your dedication and passion for women’s sexual health has made #HERstory! #ThankYouFDA

— Even The Score (@Eventhescore) August 21, 2015

In June, Sprout raised another $50 million to back the drug’s launch, bringing its total war chest to $100 million.

“It was unprecedented,” says New York University sex psychologist Leonore Tiefer, who voiced her opposition to the drug in an open letter signed by about 100 other health professionals. “The amount of money involved meant that there could be a lot of money spent in the run-up [to approval].”

The trouble with Addyi

Critics accused Even the Score of spreading misinformation.

One example: Even the Score’s literature claimed that 26 drugs have been approved to treat sexual dysfunction in men and none in women. Skeptics retort that there has never been a medication that treats low libido in males and only eight approved for sexual dysfunction.

Other women’s health groups also say Even the Score is unabashedly hijacking the feminist narrative for the sake of profit or duping feminist-leaning organizations that don’t fully understand the issue.

Judy Norsigian, co-founder of an advocacy group called Our Bodies Ourselves, says loss of libido is a real medical condition that has become the victim of an ineffectual medication.

“The whole idea of attacking the FDA for sexism is absurd,” says Dr. Adriane Fugh-Berman, director of Georgetown University’s PharmedOut program, which analyzes the drug industry’s sway on medical professions and public information. “It’s not feminist to hold women to a lower standard — which is essentially what they were asking.”

Fugh-Berman, who was a lead author of another opposing open letter co-signed by around 200 health professionals, claims Addyi is a victim of “disease branding,” or creating medical diagnoses for everyday problems. It’s the phenomenon that has turned impotence into “erectile dysfunction” to sell Viagra, heartburn to “gastroesophageal reflux disease” to better serve Nexium and Prilosec and sliced anxiety and depression into more discrete sub-segments to bundle with new antidepressants.

Fugh-Berman maintains that HSDD was originally concocted by companies looking to sell testosterone supplements in the U.S. and propagated by various corners of the pharmaceutical industries since.

“This is a disease that was invented by industry,” Fugh-Berman says. “Who’s to say what a normal level of libido is?”

Pills to increase the female libido come around every few years. Here, an herbal form, Avlimil, in 2003.

Image: Gregory Bull/Associated Press

Sprout has continued to use the term HSDD in the context of the drug despite the fact that it was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the benchmark guide for psychiatry, in 2013. The condition was instead folded into the more general designation of “female sexual interest/arousal disorder.”

It’s also unclear how many women are affected by it, since the diagnosis is so difficult to quantify. A 2008 survey cited by Even the Score pegged the number of women affected at 10% of the total population.

In public statements, Even the Score has referred to a women’s sex drive as a human right, couching the claim in a World Health Organization document.

Dr. Tobias Gerhard, a drug safety professor at Rutgers University who sat on the advisory committee for the drug, said he had no knowledge of the condition prior to the meeting, but there was little to no debate during the proceedings or in the briefing materials about its legitimacy.

He said he ultimately decided on a cautious “yes” vote because the modest benefit outweighed the risks, but he hedged it with misgivings about many of the drug’s risks that remain unknown until it is more widely used.

Whitehead, the Sprout CEO, counters that the explanation ignores the wealth of scientific research on the condition.

“I’m mystified a little bit by these comments of people who would not have women with a medical condition get treatment for a medical disorder,” Whitehead says.

A ‘human right’

To be clear, flibanserin’s public image as the “female Viagra” is wrong, medically speaking.

Viagra is strictly physiological — it increases the amount of blood pumping to the penis — and works only when taken directly before sex.

Flibanserin, which requires a daily dose, targets the more nebulous condition of lack of libido — a low urge to want sex — and affects the balance of certain chemicals in the brain.

Addyi’s interactions with alcohol create the most controversy.

Whitehead says that alcohol was allowed in the general trial for the drug and 58% of women identified as mild to moderate drinkers. The reports of fainting and low blood pressure came from a “challenge study” where participants drank two to four shots of grain alcohol in 10 minutes.

The researchers didn’t expect the volunteer participants in that study to be so heavily male and they’ve committed to holding another one in the near future, Whitehead says.

Have something to add to this story? Share it in the comments.