Doctors and other health groups across Australia have stepped up the pressure on Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull to turn back Australia’s harsh asylum seeker policies – though he is showing no public signs of shifting.

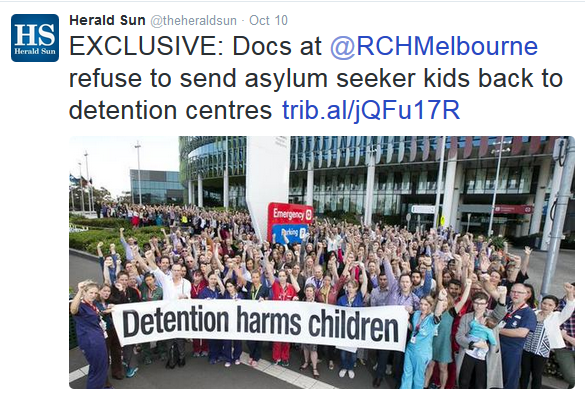

It is not clear yet whether Royal Children’s Hospital doctors are refusing, as some media reports are suggesting, to release children back into immigration detention in Australia or offshore but, calling for moral leadership on the issue, they said in an Opinion piece published (behind the paywall) in the Herald Sun on the weekend:

It is not clear yet whether Royal Children’s Hospital doctors are refusing, as some media reports are suggesting, to release children back into immigration detention in Australia or offshore but, calling for moral leadership on the issue, they said in an Opinion piece published (behind the paywall) in the Herald Sun on the weekend:

Children have nightmares, bed-wetting, and behaviour problems. They develop depression and anxiety symptoms, and their development is affected. These issues are so common they’ve become normal in detention. It is difficult, if not impossible, for us to treat these children while they are still detained.

See their full statement below, and this video from Guardian Australia. The hospital did not respond to Croakey’s query about any refusal to release children into detention.

However the AMA issued a statement praising the “principled and ethical stance” taken by the doctors, and State Health Minister Jill Hennessy also congratulated them for “acting in the best interests of their patients”. AMA President Brian Owler said:

However the AMA issued a statement praising the “principled and ethical stance” taken by the doctors, and State Health Minister Jill Hennessy also congratulated them for “acting in the best interests of their patients”. AMA President Brian Owler said:

Doctors are put in a very difficult position because, if we had a child that comes into our hospital that we feared if sending them back to an environment which we felt was going to be harmful, where they were at risk of abuse, we would be negligent if we sent them back to that environment. And that is what the doctors at the Royal Children’s Hospital are saying. We cannot send children back to an environment where they’re going to be harmed. Why are these children treated as any less of a citizen, as any less of a human, than our own children?

Liberal backbencher Russell Broadbent, who has previously crossed the floor to vote against tough asylum policies, told ABC radio that public opinion has shifted on the indefinite detention of asylum seekers.

“Long-term indefinite detention is not good enough in this country. It always comes to this; I knew it would come to this. It’s come to this again. The Australian people standing up and saying nup, not on. Not in our country,” he said.

“These people are not leftie activists,” Broadbent said of the Royal Children’s Hospital doctors. “The Australian people, through the children’s hospital, have shifted. And they’ve said, our detention policies are not good enough.”

Labor frontbencher Lisa Singh also broke ranks to call on ABC TV’s Q&A for an end to ‘inhumane’ indefinite offshore detention

Also yesterday a large group of mental health groups and advocates called on the Prime Minister to release all children and their families from the detention centres on Nauru and Manus Island. They said their call his letter was in response to the quarterly health report by the International Health and Medical Services (IHMS) group, that provides health care to Australia’s detention centres, that showed deteriorating mental health among both adults and children. The report, released under freedom of information laws, said 44 per cent of children in offshore detention required the attention of a mental health nurse between October-December 2014.

In Question Time, the new Prime Minister was sticking to the mantra that the alternative to detention was asylum seekers drowning at sea. But he is being reminded of his previous comments that:

“The bottom line is this: one child in detention is one child too many. Everyone is anguished by having children locked up in detention,” he said.

***

Statement from Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital doctors:

At the Royal Children’s Hospital we look after children.

We provide care for all children — including children in immigration detention.

It’s our job to make sure children are well, and our role and responsibility is the health and safety of children, working with others in the community, and each child’s family.

Our experience is that detention harms children and families.

Many of the children in detention we see at the RCH have been there for a long time — 18 months to two years, sometimes longer.

For some children, this is more than half their lifetimes. For babies born in detention — it’s their whole life.

Detention centres have guards, fences, and checkpoints. Guards take children to school. Guards bring these children to the RCH, and stay at the door of their room or clinic for as long as the child is at the hospital.

In detention, families are not able to function. Everyday activities, that we take for granted in the community, are not possible. Parents are not able to cook for their children. They cannot take them to school, or have space to be alone as a family.

Over time, we see parents and children fall apart under this strain.

They develop severe mental health problems and lose hope for the future.

We see parents become overwhelmed and lose their confidence. Some parents can’t care for their children because of their own mental health problems.

Children have nightmares, bed-wetting, and behaviour problems. They develop depression and anxiety symptoms, and their development is affected. These issues are so common they’ve become normal in detention. It is difficult, if not impossible, for us to treat these children while they are still detained.

Detention centres are not safe for children. Children are exposed to the distress, violence and mental health problems of adults, and parents cannot protect their children from these circumstances.

We are concerned about the impact of detention on children. We are concerned about the children who remain in detention today.

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the Australian people have shown compassion and leadership in response to Syrian refugees.

The Victorian Government has shown a longstanding commitment to refugee health. We can be proud of these responses, however we cannot lose sight of the children who remain in indefinite detention.

While many children were released earlier this year, there are still close to 100 children in detention in Australia, with a similar number on Nauru. There have been no public statistics about children in detention since May.

We are responsible for providing the best possible care to the child in front of us.

We recognise the fact that while they may be labelled an asylum seeker, they are a child with a family that loves and worries about them.

We see an engineer and teacher with a four-year-old; the nine-year-old who wants to play football; the single dad who is finding parenting tough.

When we use these terms to describe our patients, we acknowledge the people caught within the policies.

When we use a different language to talk about these families — calling them “boat arrivals” or “illegal maritime arrivals” — we start to accept their situation in detention — one that we would not accept for other children, or for our own children.

We believe there are many, many Australians who share our concern.

As health staff at a leading children’s hospital, our duty is to support child health.

We cannot accept or condone harm to children. Detention causes harm and it must end.

We call for moral leadership on this issue to find a solution, quickly — to use alternatives to detention and to stop the harm.