Scientists studying stroke-related brain damage may have just stumbled upon a major breakthrough in our understanding of addiction.

While monitoring the recovery of more than 150 stroke patients who were all smokers, researchers found that those who suffered a stroke in a brain region called the insular cortex were far more likely to quit smoking and experience fewer and less severe withdrawal symptoms than those with strokes in other parts of the brain.

The research, published in two articles in the journals Addiction and Addictive Behaviors, suggests that the insular cortex may be critically involved in the development of addiction and thus could be crucial in treating addictive disorders.

“These findings indicate that the insular cortex may play a central role in addiction,” reports lead author Dr. Amir Abdolahi, a clinical research scientist at Philips Research North America. “When this part of the brain is damaged during stroke, smokers are about twice as likely to stop smoking and their craving and withdrawal symptoms are far less severe.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the U.S., accounting for more than 480,000 deaths every year.

Due to the addictive qualities of nicotine, most smokers find it very difficult to quit once they have developed a habit. While smoking rates have fallen in recent years, from approximately 21 of every 100 adults in 2005 to 18 of every 100 adults in 2013, cigarette smoking is still the cause of 1 in every 5 deaths in the U.S.

At present, prescription drugs that are used to help people quit smoking work by disrupting “reward” pathways in the brain that respond to nicotine. Unfortunately, this form of treatment has a high rate of smoking relapse, with an estimated success rate of less than 30% after 6 months. Nicotine patches and lozenges have a similar rate of success.

Previous studies have suggested that the insular cortex region of the brain could play an important role in the cognitive and emotional processes that facilitate addiction, but the functional implications were not clear — in other words, scientists weren’t sure if changes in this region of the brain could actually have an effect on the use of addictive substances. This latest research is the first to provide an answer to that question.

‘It is clear that something is going on in this part of the brain that is influencing addiction’

In the new studies, researchers measured two different sets of smoking cessation-related indicators in recovering stroke patients: how severe their cravings were during hospitalization from their stroke and whether or not they resumed smoking following their stroke.

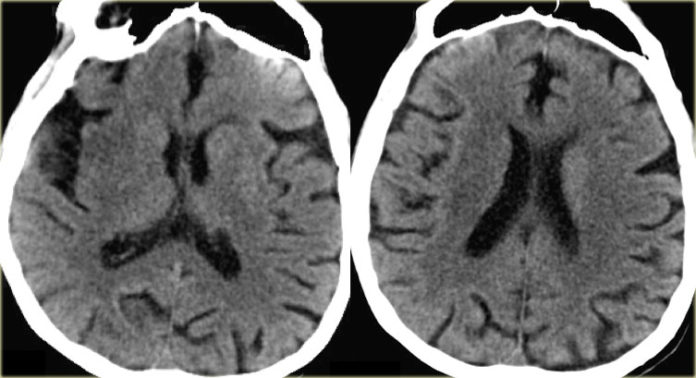

A total of 156 patients with stroke were assessed in the study, all of whom were active smokers. The researchers determined the locations of their strokes using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) and divided the patients into those whose strokes occurred in the insular cortex (38 patients) and those whose strokes occurred elsewhere (118 patients).

A total of 156 patients with stroke were assessed in the study, all of whom were active smokers. The researchers determined the locations of their strokes using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) and divided the patients into those whose strokes occurred in the insular cortex (38 patients) and those whose strokes occurred elsewhere (118 patients).

After measuring multiple aspects of withdrawal during hospitalization, the researchers found that the patients who had strokes in the insular cortex experienced fewer and less severe withdrawal symptoms compared with the patients whose strokes occurred in other brain regions.

The researchers also followed up the patients 3 months after their strokes, assessing their self-reported smoking status and any abstinence from nicotine products. They found that an impressive 70% of patients with strokes in the insular cortex had quit smoking, compared to just 37% of patients with strokes in other parts of the brain.

Although the studies involved a relatively small number of patients who experienced damage to the insular cortex, the researchers say these results support the potentially critical role of this area of the brain in maintaining smoking and nicotine abstinence. As such, the team hopes to use their findings to explore therapies that could target this area of the brain and disrupt its role in addiction, possibly with new drugs or other techniques such as deep brain stimulation or transcranial magnetic stimulation. They also speculate that, in addition to smoking, the role of the insular cortex could apply to other forms of addiction.

“Much more research is needed in order for us to more fully understand the underlying mechanism and specific role of the insular cortex,” said Dr. Abdolahi, “but it is clear that something is going on in this part of the brain that is influencing addiction.”