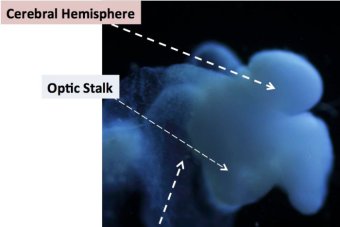

An almost fully formed brain has been grown in a laboratory for the first time, scientists from Ohio State University say.

The unconscious brain, the size of a pea and comparable with a five-week-old foetus, could speed up neuroscience research into conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

The model brain was engineered from adult human skin cells but the method is largely under wraps because of a pending patent.

Lead researcher Professor Rene Anand, who presented his data at a military health symposium in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, said they had reproduced every part of the brain.

“Not only does it look like a brain, it is expressing all of the genes that help make a brain, and that means the entire thing from cortex to the spinal cord is present,” he said.

However, the brain does not have the capacity to be conscious and Professor Anand said ethical concerns were therefore non-existent.

“It has no sensory input whatsoever, so largely it is a living tissue that replicates the brain,” he said.

“And when there are genetic causes or environmental causes, we can assess how they alter the migration of cells, for example, or the formation of synapses or the formation of circuits.

“So it gives us incredible access to knowing when something goes wrong, how does it go wrong, and maybe one day we’ll figure out how to fix it.”

The Guardian has reported several researchers they contacted were concerned the data was being kept under wraps and it had not gone through peer review.

They said that made it impossible to judge the quality and impact of the model brain.

Researchers deny details being kept away from scrutiny

But Professor Anand said his team was not keeping it a secret.

“Actually the data has been used in several different federal and private agency grants,” he said.

“Many of their scientists have seen all of the data and I think The Guardian article probably refers to scientists who are correctly being cautious.

“I think when you make a claim like this, any good scientist would want to see all the data, but that data will become publicly available after we complete our invention disclosure process.”

The researchers said the next step would be to attempt to build the vasculature, which is the blood supply.

The model brain will then become useful to treat things like stroke.

“As a constant of [the vasculature], the brain will mature further,” Professor Anand said.

“I think that will allow us to ask questions about disorders that are in the dementia category.”

Discovery to assist with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s

Professor Anand said the model brain could have huge impacts on research into neurological diseases and would accelerate of research.

“I think it’s ethical, because it will make greater predictions of what is going to happen to a patient who is given a drug, both on the efficacy side and on the side-effect side,” he said.

“You won’t have to jump straight from rodents into humans. It will drop the cost of clinical trials dramatically — this is a lot cheaper to do than clinical trials.

“I think its predictive capacity will be phenomenal because it is human.”

Professor Anand said it could help particularly with conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

He said the researchers would test it on people who have huge genetic proclivity in families.

“Where we will run into possible trouble is when over a lifetime exposed to certain types environmental toxins and not knowing what they are, we will probably have a harder time trying to discern how that comes about and why,” he said.

“But it’s also a model that allows us to ask questions about pre-natal health — what happens to a pregnant woman who is smoking smokeless nicotine? Is it safe?

“Or are you drinking water where plasticides are added to the plastic — is it safe?

“We can ask these questions in human models, make predictions and provide guidance to the FDA [US Food and Drug Administration] to regulate or not regulate or to provide that information to the public.”

Professor Anand said he foresaw a time when the brain model would open doors to understanding traumatic brain injuries and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

“Recently at the military health sciences conference we allowed defence agencies to see the technology we brought to the table,” he said.

“Our hope is that if they fund us we’ll be able to do what we’re trying to do for, say, autism or Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s — get skin cells from those who have been traumatised, that have PTSD and those who don’t have PTSD, and then we ask what’s the difference.

“The question would be, for example, you’d use stress hormones and, say, does this person’s brain react more adversely to it than the other person, and is that why they get PTSD or is it not?”