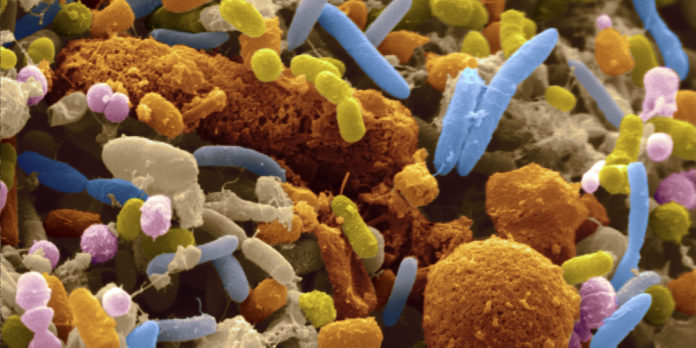

Imbalances in intestinal bacteria induced by stress in early life may play a key role in the development of anxiety and depression in adulthood, according to a new study published in Nature Communications.

The findings are consistent with a growing line of research showing that the diverse colonies of bacteria living in the gut can have a major influence on brain function and mental health. Though researchers have long known that the brain sends signals to the gut — that’s why stress and other emotions can contribute to gastrointestinal symptoms — recent evidence shows that these signals travel the opposite way, as well.

This latest study, led by researchers from McMaster University in Canada, is the first to explore the role of the gut microbiome as a potential link between early-life stress and the development of mental disorders later in life. The results suggest that exposure to stress early in life can induce permanent changes in the composition and metabolic activity of gut bacteria, which in turn lead to alterations in brain chemistry that increase vulnerability to depression and anxiety.

For the study, the researchers subjected infant mice to stress by separating them from their mothers for 3 hours each day when they were between 3 and 21 days old.

The first phase of the experiment was conducted with mice that were exposed to an ordinary, complex range of bacteria and had normal gut microbiomes. After being subjected to maternal separation, the mice showed an abnormal increase in the stress hormone corticosterone. They also displayed signs of anxiety and depression. Additionally, the mice were found to have imbalances in gut bacteria, which the researchers attributed to the release of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter involved in the stress response that communicates between the body and the brain.

Then, the researchers repeated the experiment in a germ-free condition where the mice were not exposed to any bacteria. Half of these mice served as a control group and were not subjected to maternal separation; naturally, this groups showed no elevated stress hormone or altered behavior. The other half of the germ-free mice were subjected to the same period of maternal separation as the mice with normal gut microbiomes. Interestingly, even though the germ-free mice showed also showed abnormally high stress-hormone levels and gut dysfunction after being subjected to stress, they didn’t show any signs of anxiety or depression.

When those same stressed, germ-free mice were colonized with bacteria, however, they began showing anxiety and depression-like behavior within a few weeks.

Finally, the researchers wanted to see how the control group — the germ-free mice who had not been separated from their mothers — reacted when they were exposed to bacteria from the stressed mice. In this situation, the mice didn’t show any signs of depression or anxiety.

Communication breakdown

What does it all mean? Imbalanced gut bacteria alone wasn’t enough to bring on anxiety and depression. Instead, the findings suggest that the interaction of changes in the gut microbiota and early-life stress may be what determines an individual’s likelihood of developing anxiety and depression.

“We are starting to explain the complex mechanisms of interaction and dynamics between the gut microbiota and its host,” said senior study author Dr. Premysl Bercik, associate professor of medicine at McMaster’s Michael G. DeGrotte School of Medicine. “Our data show that relatively minor changes in microbiota profiles … can have profound effects on host behavior in adulthood.”

“But,” he adds, “it’s not only bacteria, it’s the altered bidirectional communication between the stressed host — mice subjected to early life stress — and its microbiota, that leads to anxiety and depression.”

Communication between the brain and the gut takes place via gut-brain axis, a mode of bidirectional signaling between the digestive tract and the nervous system.

Communication between the brain and the gut takes place via gut-brain axis, a mode of bidirectional signaling between the digestive tract and the nervous system.

There are several central mechanisms by which gut bacteria can communicate with the brain.

First, imbalances in gut bacteria can set off an immune response marked by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can actually change how our brain cells communicate. While the evidence is still emerging, recent research suggests that brain inflammation triggered by this immune response may play a role in the development of depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders.

Secondly, gut bacteria can produce neurotransmitters, which are carried through the blood to the brain. For example, the gut manufactures about 95 percent of the body’s supply of serotonin, which influences both mood and GI activity. Additionally, gut bacteria can communicate directly to the brain in its own language via the vagus nerve — if you’ve ever felt “butterflies” in your stomach, this is what you experienced.

The good news is that you can support gut health (and therefore mental health) by eating a diet that’s rich in probiotics — the “friendly” gut bacteria that support digestion and a balanced microbiome, and are known to boost immune and neurological function.