On a Monday morning in March of 2005, William, a British soldier stationed in Germany, woke up and headed to the dentist for a scheduled root canal. Ten years have passed, and yet upon waking every morning since that day, William still believes it’s March of 2005, that he is a British soldier stationed in Germany, and that he will soon be headed to the dentist for a root canal.

Something, in other words, happened between the time the surgery began and the time it ended — something that has prevented him from forming any long-term memories since the day of his dental surgery. When he forms new memories, they now only last about 90 minutes, according to the case report his medical team recently published in the journal Neurocase.

“We had never seen anything like this before in our assessment clinics, and we do not know what to make of it,” said Dr. Gerald H. Burgess, a clinical psychologist at the University of Leicester and one of the co-authors of the case report.

The Patient

William was a member of the British Armed Forces, who at 22 married his wife, Samantha, according to the BBC, though reporter David Robson notes that he changed both names to protect the couple’s privacy. They have two children, who are now 21 and 18. On the morning of March 14, 2005, he woke up, went to the gym, stopped in at his office to take care of some emails, and went to the dentist. “I remember getting into the chair and the dentist inserting the local anaesthetic,” William told Robson. It’s the last thing he remembers.

The Problem

After the surgery, William was pale, and his eyes were “vacant” and unfocused, his physicians write in the case report. The dentist suspected that he might have fainted during the procedure and that his blood pressure was reduced, so he gave him glucose tablets and high-flow oxygen. When he hadn’t improved by 5 p.m., he was taken to the hospital, where he stayed for three days. There, it became clear that he’d somehow lost his ability to form long-term memories; it was like his brain rebooted every ten minutes. For the next month, the man was only able to retain the awareness of new events for about ten minutes after they occurred, and then he had no memory of them. While in the hospital, his memory improved a bit, so that he had a “90-minute span of awareness,” but it has not improved in the ten years that have passed since then. “He wakes up believing that he should still be in the military, stationed abroad,” the case report authors write. “Every day he thinks it is the day of the dental appointment.”

Like something out of Memento or 50 First Dates, his wife has entered a guide to his present life in the notes section of his smartphone, titled “First thing — read this.” There, he learns every day what happened to him that day at the dentist, and that his children have now grown into young adults.

The Diagnosis

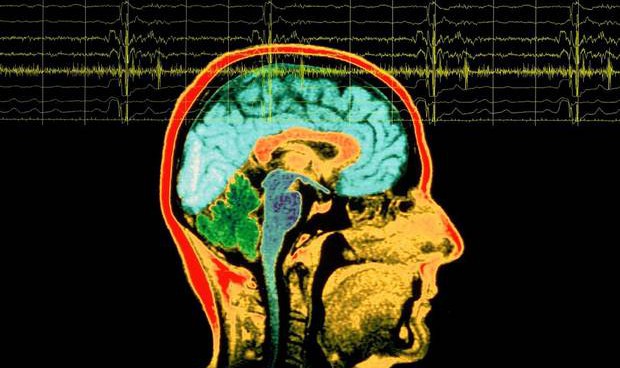

William’s symptoms would suggest that he has anterograde amnesia, an inability to create new long-term memories, while memories formed before a brain injury are accessible as normal. Yet imaging scans show no damage to the regions of the brain typically associated with this type of memory loss, and the doctors couldn’t find anything in the man’s medical history (like a head trauma) that could explain the symptoms. Next, they speculated that the condition might have had something to do with the stress related to the funeral of his grandfather, which he attended a few days before the incident. This type of amnesia, called psychogenic amnesia, typically follows a severe psychological trauma. But William’s wife and doctors don’t think this diagnosis fits his case, either, as he showed no signs of emotional problems before his memory loss, and his symptoms are inconsistent with other cases of psychogenic amnesia. Doctors also thought that his amnesia symptoms could be an unusual reaction to the anesthetic used during the dentist appointment, which might have resulted in unspecified damage to the brain — yet they were unable to find a single case where this has ever happened.

And there are numerous other possibilities about what may have caused the amnesia: “A previous latent genetic disorder triggered by a mild trauma event? Microscopic brain damage undetectable by modern brain scanning technology? A very elaborate and unusual psychiatric amnesia?” Dr. Burgess still wonders.

Dr. Burgess does have a theory, outlined in the BBC write-up of the case:

Once we have experienced an event, the memories are slowly cemented in the long term by altering these richly woven networks. That process of “consolidation” involves the production of new proteins to rebuild the synapses in their new shape; without it, the memory remains fragile and is easily eroded with time. Block that protein synthesis in rats, and they soon forget anything they have just learned. Crucially, 90 minutes would be about the right time for this consolidation to take place – just as William starts to forget the details of the event. Rather than losing its printing press, like Henry Molaison [whose experiences after brain surgery have informed much of what we know about memory], William’s brain seems to have simply run out of ink.

Dr. Burgess hopes that after the publication of the case report, he’ll hear from other psychiatrists and neurologists who have seen similar cases, which could eventually help William. Unless that happens, William may live the rest of his life with a memory that erases itself every 90 minutes.

“Though over the years he has implicitly adjusted to his circumstances to some extent, in general each morning he is surprised to wake up in his mother’s house,” the authors wrote in the case report. “He wakes up believing that he should still be in the military, stationed abroad.”