Summer is here. By the end of the season, many children in the United States and U.K. will have undergone FGM.

Despite the existence of laws and policies to safeguard against FGM in the U.S., 50,795 women and girls across the country are at risk of undergoing FGM.

It is estimated that over 140 million girls and women alive today have undergone some form of FGM.

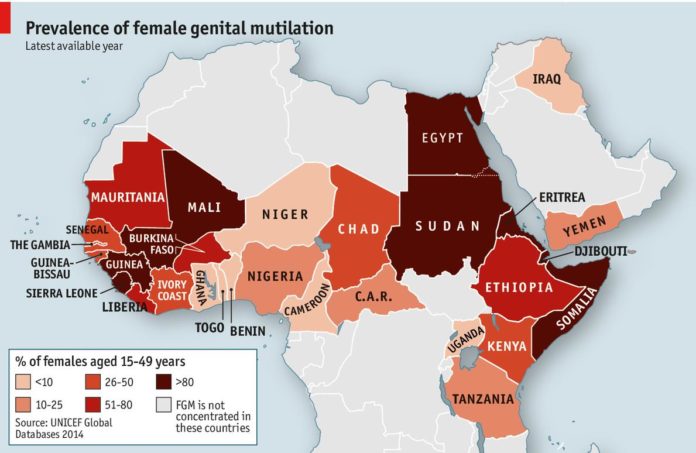

World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 125 million girls and women alive today have been cut in the 29 countries in Africa and Middle East where FGM is concentrated.

FGM Implications

FGM includes procedures that intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons (WHO).

FGM is normally carried out on young girls from infancy to 15 years of age. The type of FGM performed depends on a girl’s culture and religious or geographical background.

WHO has classified FGM into four categories. A close scrutiny of the types of FGM reveals a deep-seated fiendishness and the gravity of the practice.

Clitoridectomy involves partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce while Excision entails partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora.

Infibulation requires narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal formed by cutting and repositioning the inner or outer labia, with or without removal of the clitoris.

In addition, FGM may include other harmful procedures, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.

In poor countries, the procedures are mostly performed under poor hygienic conditions often with unsterilized equipment, e.g. rusted blades/knives that can cause infections.

In communities where large groups of girls are cut on the same day as part of a socio-cultural rite, there are increasing risks of HIV transmission through use of shared instrument for a number of operations.

Also, when FGM procedure is done under a traditional setting with no anesthetic or medical treatment, victims often endure prolonged excruciating pain and extended recovery time.

Ttreating women as a second class citizen is a bad tradition.”

By President Barack Obama, Global Entrepreneurship Summit Tour to Africa. Nairobi, Kenya. 26 July 2015. (Source: CNN News)

Immediate FGM complications include severe pain, shock, hemorrhage (bleeding), tetanus or sepsis (bacterial infection), urine retention and open sores in the genital region and injury to nearby genital tissue that can also result into secondary infections.

The long-term consequences comprise cysts, menstrual difficulties, recurrent bladder and urinary tract infections, increased risk of childbirth complications and newborn deaths, possible blood-borne infections such as Hepatitis B & HIV, scarring and keloid.

The damage to the urethra during FGM may lead to obstetric fistula and urethral strictures.

For those who’ve undergone Infibulation, the need for later surgeries to allow for sexual intercourse and childbirth presents further health risks and complications.

The long-term emotional impacts and psychological trauma, though immeasurable, are irreparable and life-long.

Infertility is another long-term consequence of FGM. Ironically, in various cultures where FGM is practiced, infertility is considered a woman’s fault. Women with infertility problems often experience isolation and exclusion especially by community members notably in-laws.

Beyond the physical, emotion and psychological impacts, lies the shame that FGM victims have to persevere. Many women are embarrassed to seek regular genealogical check-ups and medical treatments.

That was the case with a woman who endured abdominal pain for 15 years but did not seek treatment from a doctor due to shame.

FGM Challenges

Ending FGM entails a little more than just telling someone or a group to stop the practice. A clear understanding of these challenges can help steer way into achieving an end to the practice.

The first of a host of FGM challenges is the fact that many victims may not necessarily be aware that they are “victims” due to a young age or as a result of being entrenched into a cultural belief.

Victims may not be aware of the source of the gynaecological complications that they experience, e.g., a woman may grow up believing that pain during sex is normal. After all, that’s all she has known.

Girls grow up knowing that FGM is part of their tradition or identity and because they want a continuation of this into the next generation, when they become parents, they are more likely to have their children undergo FGM as well.

In essence, FGM is a violation of the human rights of girls and women. In his speech in Nairobi-Kenya, US president Barack Obama condemned FGM practice and stressed on the need for gender equality: “Treating women as a second class citizen is a bad tradition,” he said, to the applause of his listeners.

Complicity by health care professionals who perform FGM legitimizes the practice by creating a false sense of security. For as long as FGM is performed by a nurse or a medical practitioner, it is perceived as “safe” and “mild.”

Sometimes FGM is termed “female circumcision” or “female cutting.” These names make it sound as though FGM is counterpart to male circumcision.

It is obvious that FGM is not simply a “female version” of male circumcision. The social, physical, psychological, emotional and the health implications of the two are adversely divergent.

In 2012, The American Academy of Pediatrics published a report that concluded that the health benefits of newborn male circumcision outweigh the risks. There are no such benefits associated with FGM.

WHO also had a report that male circumcision can reduce the spread of HIV. The validity of this finding remains controversial, but if true, unfortunately women who undergo FGM are unable to amass such gains.

That said, it should be noted that even though the health risks associated with FGM far outweigh those linked to male circumcision, the latter procedure is not without its share of dangers.

Male circumcision has the potential to cause injuries to the urethra as well. It can also cause excessive bleeding and death.

National Health Service (NHS) reports that male circumcision reduces sensitivity, i.e., that uncircumcised men experience more pleasure during sex than their circumcised counterparts.

Another FGM challenge revolves around the fact that whenever FGM is simply dismissed as a cultural practice, not too many people from outside of the culture where it is practiced are likely to condemn it, due to fear of “meddling in a people’s culture.”

Lack of actions at grassroots and political levels denies FGM a platform as a health and social priority.

The secrecy surrounding FGM practices in certain cultures, shields the practice from the outside world. It is this confidentiality that sometimes allows for FGM procedures to go undetected even in places with laws and policies to safeguard against it.

In 2011, Kenya passed a law that makes FGM illegal and yet, in some parts of the country, the practice persists. In those areas, FGM practice is deeply rooted into the culture that some lawmakers may find it difficult enforcing the law.

In many cultures, FGM is a respected tradition that’s linked to purity and community acceptance. Having a “breakthrough” in such cultures may pose challenges as well.

To date, there is no scientific evidence that suggests any benefits of FGM.

Many FGM victims often find themselves subdued in a societal/cultural/religious quagmire where on the one hand, there exists a compelling need to sustain a “sense of belonging” to their communities and on the other hand, they are judged and obliged to conform to antiquated norms that threaten and degrade the very existence for which they strive.

There still exists enormous need to create FGM awareness.