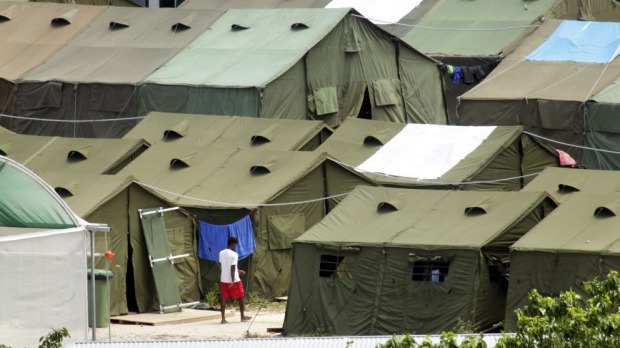

A refugee wanders through the tents at the Nauru detention centre. Photo: Angela Wylie

An Iranian toddler detained on Nauru had visible signs of tuberculosis for three months before medical tests were ordered and was then forced to wait three weeks for medication to arrive after he tested positive to the deadly bacterial infection.

By the time the medicine arrived, his parents had grown so suspicious about the urgency of the treatment they declined to administer it for another three weeks.

Sydney paediatrician David Isaacs has risked imprisonment under the federal government’s detention gag laws to speak about the case, which he said was symptomatic of a broader indifference to the wellbeing of children on the island by the healthcare contractor International Health and Medical Services.

Children with tuberculosis are not infectious to other people.

Dr Isaacs detected a swollen node under the boy’s arm while visiting the island in December and immediately ordered a TB test.

The enlarged node – a classic sign of tuberculosis – had been present for three months and he had been underweight with lumps on his neck for six months.

“Once the medication arrived the parents said, ‘If it’s that important why didn’t you get the medicines earlier?”‘ Dr Isaacs said.

“IHMS frequently claim that healthcare on the island and for asylum seekers generally is comparable to that given in Australia. This is the sort of thing that tells me it’s not.”

The boy was transferred to Villawood for treatment and will soon return to Nauru.

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection said it had started to screen child detainees for tuberculosis in December.

“The time frame for the implementation of routine screening of children for latent TB was influenced by consultations with experts in the area and procurement of material as well as training for staff,” the department said.

“A person with infectious TB is medically isolated and treated until no longer infectious. Contact tracing is undertaken, to identify others who may have been at risk of exposure.”

TB screening was not routine for children at the time it was detected in the boy, despite a recommendation from a previous paediatrician.

IHMS, which has a $1.6 billion contract to provide healthcare to asylum seekers, has struggled to meet its commercial obligations while providing appropriate care.

An internal report leaked to The Guardian indicated the company believed fraud was “inevitable” if it was to meet government targets.

An independent audit of healthcare records kept by IHMS showed that children were receiving the vaccinations they required only 7 per cent of the time and asylum seekers were seeing GPs within three days of making the request only 29 per cent of the time.