A woman in Clallam County, Washington has died from complications caused by measles, health officials said Thursday, marking the country’s first measles death in over a decade.

The woman’s measles was undetected and confirmed only through an autopsy, according to the Washington State Department of Health. Authorities did not identify the woman, but said she was likely exposed to measles at a local health facility during a recent outbreak in the area earlier this spring. She was at the hospital at the same time as a patient who later developed a rash and was diagnosed with measles. Patients with measles can spread the virus even before showing symptoms.

The woman, who died of pneumonia, had other health conditions and was taking medications that suppressed her immune system, the health department said. She was in her early twenties.

Pneumonia is one of several serious common complications of measles and the most common cause of death from the virus, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About one in 20 children who get measles will develop pneumonia. Overall, the measles virus kills about two children out of every 1,000 infected.

It’s not surprising that the woman had no obvious measles symptoms; people with compromised immune systems often don’t develop a rash when infected with the virus, as the rash is a product of a functioning immune response. But without the characteristic rash, doctors did not immediately link her illness to measles. It was only after her death that they discovered she had died of measles-induced pneumonia.

Health officials said the woman’s death was a preventable, but predictable, consequence of falling vaccination rates.

“This tragic situation illustrates the importance of immunizing as many people as possible to provide a high level of community protection against measles,” the state health department said in a statement. “People with compromised immune systems often cannot be vaccinated against measles.”

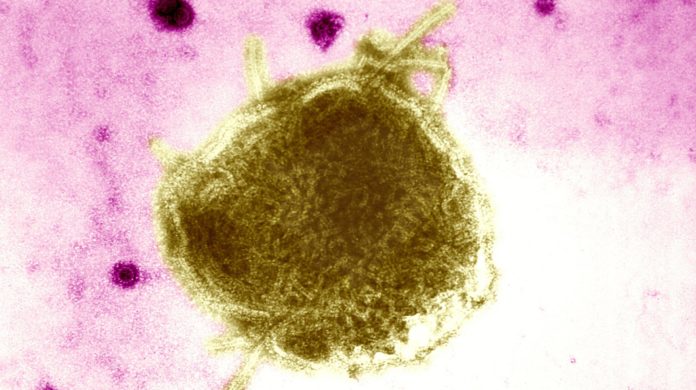

The American Academy of Pediatrics calls measles “one of the most highly communicable of all infectious diseases.” The main symptoms of the virus include fever, red and sore eyes, runny nose, cough and a rash, but it can also cause deadly health complications, particularly pneumonia and encephalitis. It is spread by contact with an infected person through coughing or sneezing, and it can remain in the air and on surfaces for up to two hours.

While once widespread in the United States, cases dropped significantly because of vaccines, and in 2000, measles was effectively eliminated in the United States, according to the CDC. However, the disease has surged back in recent years as a growing number of parents have chosen to refuse or delay vaccination for their children. Last year brought the highest number of recorded measles cases — 644 nationwide– since 2000, the CDC says.

This newly confirmed case marks Washington’s 11th reported instance of measles this year, and the 178th case in the country. Two-thirds of this year’s cases, the CDC notes, were “part of a large multi-state outbreak linked to [Disneyland] in California.”

In response to the Disneyland outbreak, California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) this week signed one of the nation’s strictest laws regarding school vaccinations. The law, scheduled to go into effect for the 2016-2017 school year, bans vaccine exemptions based on personal beliefs, which have been used with increasing frequency by parents who fear a now-debunked link between vaccines and autism, or cite other unfounded worries about the health effects of children receiving shots.

Even though more than 107 independent research studies have disproven any supposed link, some parents are still refusing to allow their children to be immunized. As science reporter Maryn McKenna points out, “When people prevent or delay their children’s vaccinations, it isn’t only their children they put in danger.” She continues:

“The fence of protection that vaccine-induced immunity throws up around all of us protects not only those who are vaccinated, but those who can’t be: infants too young to get the vaccine and anyone who, like the Washington woman, possesses an immune system undermined by medical treatment or biological hazard.

Those unknown vulnerables represent a lot of people: cancer patients undergoing treatment, transplant recipients taking anti-rejection drugs, people living with HIV, anyone with an inborn immune deficiency, anyone getting high doses of steroids—and the 4 million children in the United States who at any point are less than 12 months old, the recommended age for the first dose of measles vaccine.