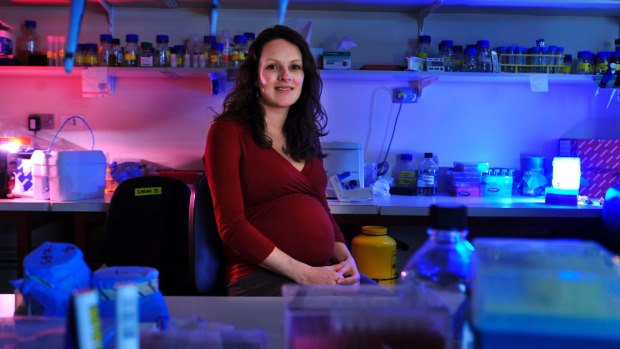

Marnie Blewitt, genetic research scientist with the Walter and Eliza Institute. Photo: Jason South

Scientists have for the first time worked out how a gene linked to one of the most common forms of muscular dystrophy works.

The discovery, by researchers at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, could lead to a treatment for a progressive type of muscular dystrophy that affects one in 8000 teenagers and young adults.

Currently there is no cure or treatment for the genetic condition, known as facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy.

Published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the discovery is important because it raises the prospect of early intervention which could treat and even prevent the debilitating symptoms from developing.

Walter and Eliza Hall researcher Marnie Blewitt discovered the gene, known as Smchd1 or “Smooch”, in 2005.

Since then, the challenge has been to establish how the gene works at a molecular level as a means to understanding how best to intervene to stop the disease taking hold.

“It was a really tricky one to work on because Smchd1 is an absolute giant,” Dr Blewitt said.

With colleagues including James Murphy and Kelan Chen, as well as researchers overseas, Dr Blewitt found it was a mutation in the “Smooch” gene which turned other genes off and triggered the onset of the degenerative disease.

The team established that the mutant Smchd1 gene switched other genes off by binding to the DNA. They were also able to establish precisely where, among the 20,000 genes in our DNA, the gene attached.

“It’s only a couple of hundred places and that’s important to know,” she said. “If we have a better understanding of how it works at a molecular level then we can intelligently design drugs that can better help the patient.”

Dr Blewitt said designing a drug that could activate Smchd1 would benefit patients with this type of muscular dystrophy.

People with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy tend to be diagnosed in their 20s and 30s, usually after developing a weakness in the shoulder and scapula muscles. The condition deteriorates until it is impossible for the patient to lift their arms and use their facial muscles, which affects speech and facial expressions.

“It means they can’t interact with people normally, which is why it’s such a cruel disease,” Dr Blewitt said. “It affects the way they participate in everyday life.”

Some patients also become wheelchair-bound.

Being able to genetically test patients with a family history of the disease before the symptoms appear, and intervening early to manipulate the behaviour of the Smchd1 gene, will prevent the muscles from degenerating.

“If we could do that, that would improve their lifestyle and they wouldn’t suffer from the disease at all,” she said.