Ebola can linger in the eyes of survivors, Aussie researcher finds

Although she lives a long way from Africa, an Australian researcher has confirmed the Ebola virus can linger in the eyes of survivors even after they’ve made a full recovery.

Justine Smith, an ophthalmology expert at Flinders University in Adelaide, co-authored a study that found the live Ebola virus could be present in a patient’s eye fluid even 10 weeks after the virus was no longer detectable in the patient’s blood.

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in May, was based on the case of Dr. Ian Crozier, whose struggle against the Ebola virus disease was detailed in the New York Times.

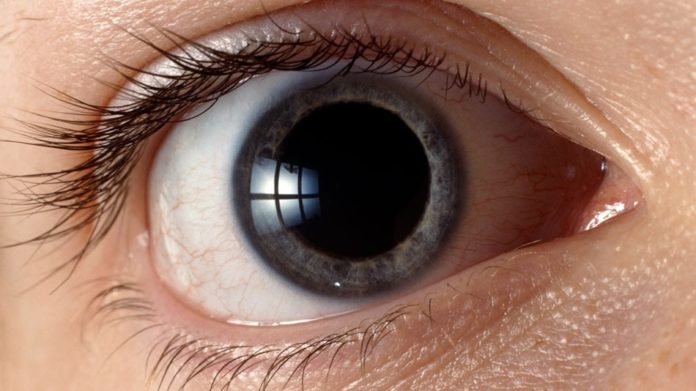

After contracting Ebola working in West Africa, Crozier was repatriated to the U.S. where he recovered from the disease in late 2014. Not long after, however, he was back in hospital with eye trouble. He had developed acute uveitis, with symptoms including climbing pressure inside the eye, fading sight and pain. One eye even changed colour from blue to green.

Uveitis is a catch-all term for inflammation inside the eye that can have an infectious or non-infectious cause.

Dr. Ian Crozier’s eye turned from blue to green.

Image: Emory Eye Center

Dr. Steven Yeh, associate professor of ophthalmology at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, removed some fluid from between the lens and the cornea of the eye for testing, Smith told Mashable Australia. After growing Ebola from the sample, Yeh consulted with eye specialists around the world on the infection, including Smith. It became clear that although the patient had recovered from the disease, there was still live Ebola virus present inside his eye.

Similar to the manner in which it hides in the eye, the Ebola virus has also been also been found lingering in semen. Smith suggested this could be because the testes and the eyes are both immune-privileged sites, meaning they are environments unique in the body with a high tolerance for antigens and the ability to reduce inflammation, even if they are infected.

Although it lingers in eye fluid, it appears highly unlikely Ebola could be passed on to another person from the eye. Yeh and colleagues took samples from the surface of the eye and tears, Smith said, but they were unable to grow Ebola from that material. “Casual contact is of no risk to everyone around you,” Smith said. “You wouldn’t be able to pass on the disease that way.”

There is a potential risk during surgery, however, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the U.S. does recommend survivors practice safe sex until they’re given the all-clear.

Justine Smith.

Image: Flinders University

Without further testing, it’s hard to know the extent of the issue or whether uveitis could occur in all those who survive Ebola, Smith said.

In previous outbreaks, the number of those infected with the virus was smaller, and there were fewer survivors. “Now there are thousands of survivors, so we’re starting to get a picture of what they might be facing moving forward,” she added. “You can’t conclude anything with one patient, and you need more numbers.”

This lack of comprehensive testing also means it’s unclear what effect ebola-associated uveitis could have long-term. In general, however, untreated uveitis can cause serious complications, from cataracts and glaucoma to retinal detachment.

Depending on the cause of the uveitis, the issue can sometimes be treated with anti-viral medication or certain drugs that suppress the immune system.

The next step, Smith said, was to work with survivors globally to determine the extent of the problem, how to manage it and how to mitigate the risk to healthcare workers. “From the point of view of science, finding out why the virus was able to hide in the eye is a fascinating question,” she added.

Have something to add to this story? Share it in the comments.