In a world first, Melbourne scientists have captured on video each stage of death of a human white blood cell, a phenomenon never seen before and which reveals the cells apparently try to alert their immune system allies that they are dying.

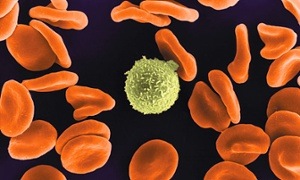

White blood cells are the critical, disease-fighting cells of the immune system which fight bacterial and fungal infections, as well as viruses.

Using time-lapse microscopy, which allows very fast events to be captured by taking hundreds of photographs every second and then viewing them in a sequence at high speed, the La Trobe University scientists saw molecules being ejected from inside the dying white blood cell.

Until now, scientists believed cells died and fell apart in a random process. The time-lapse “video”, however, shows their death is highly controlled and deliberate. The findings were published in the prestigious international medical journal, Nature Communications, on Monday.

Cell biologist Georgia Atkin-Smith was co-leader of the team to capture the process, which she said shows cell death comprised three stages; bulging, exploding and breaking apart.

“So when the cell starts to die it forms these lumps which push outwards and when the cell then explodes, it shoots out long ‘beaded’ protrusions which look like a necklace, which then breaks apart into individual ‘beads’,” she said.

“The cells around them can easily engulf these smaller pieces. But we also think there are certain molecules in the beads that, when eaten by a live cell, can signal back a warning to other white blood cells cells to say ‘Look out, there may be a pathogen coming to get you’.”

The process had never been captured before because scientists usually observed cells after they had already died, Atkin-Smith said.

Atkin-Smith said when she first witnessed the process: “I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was absolutely amazing. It still is to all us.”

Their discovery, which also involved researchers from the University of Virginia in the US, was important because it gave scientists more insight into how pathogens take over dying cells and facilitate disease spread, she said.

Dr Ivan Poon, co-lead researcher and a biochemist at La Trobe university, said the discovery may help scientists better harness the body’s own defence and healing mechanisms, leading to improved treatment for diseases.

“It could be that we’ve identified the mechanics of how dying white blood cells go about alerting neighbouring cells to the presence of disease or infection,” he said.

“Alternatively, we may have discovered the transportation mechanism for a virus to infect other parts of the body. Importantly, we’ve also discovered drugs that affect this process so, once we know more, we may be able to either suppress or enhance this action.”