Click to Open Overlay Gallery

Click to Open Overlay GalleryThe chronic loss of bladder control is a complicated problem, not least because of the social stigma attached. It’s more common among older people— according to the CDC, over half of American adults at the age of 65 and over are affected by incontinence—but it can happen to anyone, male or female, young or old. And there are few options for managing the condition. Usually, people wear adult diapers or opt to get surgery done.

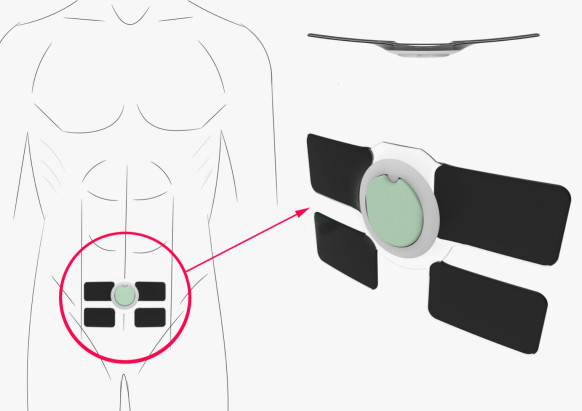

Jean Rintoul wants to provide people with another way. She’s the CEO of Lir Scientific, maker of a new wearable device called Brightly, which aims to turn the $17 billion adult diaper industry on its head. The belt-like device carries biosensors that non-invasively “see” the bladder expanding. Using Bluetooth, it can then send a discreet alert to a person’s smartphone to preemptively let them know it’s time for them to take care of their business.

“The idea is to give people back some dignity and independence,” says Rintoul, who has worked at several wearable companies, including Intel’s Basis and Emotiv, an Australian startup that develops brain-computer interfaces based on EEG technology.

Along with its unique use case, Brightly also stands out for what it’s not trying to be. At a time when Silicon Valley startup culture is widely criticized for targeting its products to a narrow population of well-off 20- to 30-year-olds, Rintoul is looking to serve a different and decidedly less glamorous market. What’s more, in setting her sights on a chronic medical problem rather than a consumer inconvenience, Rintoul may be her way to cracking a problem that few tech companies have solved: making a wearable that’s truly useful.

A Useable Wearable

A little more than a year ago, Rintoul started going to medical hackathons and reading peer-reviewed studies in search of a combination of good tech and a good concept for a medical wearable device that people hadn’t seen before. The idea for Brightly came up after she’d studied up on bioimpedance spectroscopy, a technique by which tiny electrical signals are sent through the body to non-invasively measure subtle changes in body tissue.

“I realized the bladder is one of the easiest things to see with the technology because it’s this large balloon of conductive material which is expanding and contracting,” Rintoul says.