Shoes are a new luxury for Lynne Weston.

“I can see my toes and my ankles now, and I can bend my knees. I can wear shoes again.”

Her sense of triumph is palpable, but it has not come without pain. Until recently she was confined to the house. Each morning she shuffled from bed to armchair, where she would remain all day, trapped in a 185kg body that was slowly killing her.

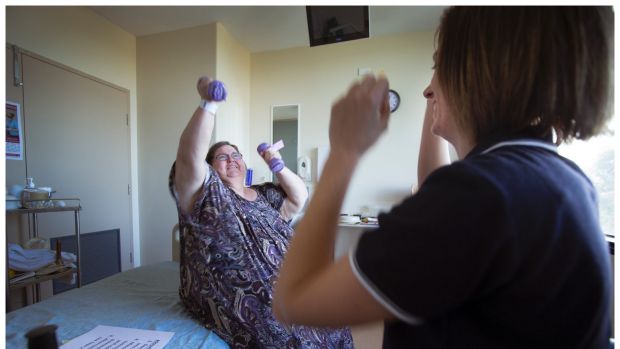

Lynne Weston doing exercises with physiotherapist Kelsey Evans. Photo: Simon O’Dwyer

Swelling in the feet and legs caused by lymphedema – a serious complication of obesity that leads to fluid build up – made wearing shoes impossible.

Too large to walk, or fit in a car, she rarely saw her four grandchildren.

“I’ve been fairly big all my life but in the last few months it got to the point where I just couldn’t do anything. I’d given up,” the 60-year-old said, breaking down. “If I hadn’t come into hospital when I did I probably wouldn’t be alive.”

Lynne Weston at Bendigo Hospital believes if she hadn’t gone to the hospital when she did, she probably wouldn’t be alive. Photo: Simon O’Dwyer

Since admission to the Bendigo Hospital on April 9 she has lost 35kg. It has been a long road – not just for her but for hospital staff.

Each day, two nurses bandage Lynne’s legs to stimulate the lymphatic system and help reduce swelling.

Her diabetes, diet and weight loss are carefully managed by a team of doctors, physiotherapists, dietitians, occupational therapists and exercise physiologists.

A normal wheelchair and one designed for obese patients. Photo: Simon O’Dwyer

The hard work will continue at home after she is discharged from the rehabilitation wing next month.

Looking after patients such as Lynne is a rising challenge for hospitals across Australia grappling with an obesity epidemic that shows no signs of slowing.

According to Australian Bureau of Statistics data, 63 per cent of adults are overweight or obese – up from 56 per cent in 1995.

A normal toilet and one designed for obese patients. Photo: Simon O’Dwyer

Like many regional areas, Bendigo in Victoria’s north-west is seeing the acute end of the problem.

Two out of every three men in the region are overweight or obese – one of the highest rates in the country.

Until now, the hospital has been equipped to deal with patients weighing between 120kg to 180kg, but in the past year the number of patients weighing more than 200 kilograms has climbed steadily.

A bed designed for an obese patient. Photo: Simon O’Dwyer

Experts believe this group is going to increase – both in the number of people who are obese, and the average weight of those who are – forcing healthcare officials to drastically rethink the design of future hospitals.

Bendigo Health’s $630 million new facility, opening in late 2016, provides a striking snapshot of what lies ahead.

It will house 27 custom-designed “bariatric” rooms, exclusively to be used by obese patients. Every ward will house one or two such rooms.

During a tour of a prototype room, The Sunday Age was given a unique insight into the costs and logistics of managing a heavier population.

Four square metres larger than standard, each $266,000 bariatric room in the new hospital will be equipped with a bigger, reinforced bed, a larger toilet, shower, wheelchair and trolley, and will be fitted with an electronically operated ceiling track hoist capable of moving patients weighing up to 300 kilograms.

Equipment costs alone are $30,000 – more than three times that of a standard room.

While there has previously been reluctance among hospital executives to talk about the financial impact of Australia’s obesity problem for fear of stigmatising those struggling with their weight, in Bendigo they say it is a conversation healthcare providers can no longer ignore.

“We just see the tip of the iceberg. There’s lots of folk seeing their GPs with type two diabetes who will never come near a hospital, at least not for the moment. But they will probably in 10 to 15 years time and it’s something we need to address as a society,” director of medicine Mark Savage said.

In the current facility, three beds in a four bed bay often have to be shut to accommodate one heavy patient. Their length of stay is on average four days longer. A shortage of larger, specialised equipment is also an issue.

The bariatric rooms in the new hospital will alleviate some of these challenges, but will add an extra $1.67 million to building costs.

“We’re getting more people who fit into the bariatric category and need beds like this to manage them safely, and they’re getting heavier as well, so it’s a double whammy,” Professor Savage said.

“They present serious challenges from a medical point of view.”

Diabetes, stroke, heart disease, pressure sores, mental health problems and an increased chance of hospital-acquired infections are among the complications.

“Surgery is also a challenge because it’s very difficult to wake these people up. A lot of the anaesthetic drugs dissolve into the extra fat tissue and the anaesthetists have to keep them in recovery for a lot longer to ensure they wake up safely,” he said.

Access to weight loss surgery in the public system is limited, with nine out of 10 bariatric operations taking place in private hospitals.

Indeed, this month a meeting of Australian surgeons heard that increasingly, obese people are being turned down for lap-band procedures because the risks outweigh the benefits.

Morbidly obese patients are often being urged to lose weight before going under the knife.

But this can be difficult for people with limited mobility.

Physiotherapist Kelsey Evans said when Lynne was admitted to hospital she could only walk with a frame to the end of the corridor.

“Now she’s walking 100 or 200 metres and can get on and off the bed by herself,” Evans said.

“Sometimes we have patients who take up to four staff just to try and roll them or get them out of bed. But the aim is we help them lose the weight so they can start doing more themselves.”

At Bendigo, a full-time employee has been appointed to oversee “safe manual handling” of obese patients due to an increase in staff injuries.

But the challenges do not end upon discharge.

Specialised ambulances are needed to transport patients home. Once there they require a bariatric bed and mattress, and regular visits from nursing staff and other therapists.

Community care for the average obese patient costs more than $43,000 a year, compared to around $7,500 for a non-obese patient.

The figures are striking, but behind the financial challenge for hospital bean counters are people battling complex problems – people like Lynne, who admits she ate “all the wrong foods”, but often did so to deal with difficult emotions.

McDonalds and KFC were her favourites. “It got to the point where I didn’t really care. I over-indulged, I ate for comfort. If I didn’t know what I wanted to do I’d think, I may as well go and eat.”

Professor Savage said the new hospital would provide better treatment, but stressed it was merely a response to the problem. The “cure” is unlikely to be a medical one.

“If you’re drunk you’re not allowed to be served in a pub, but it’s ok for fast-food outlets to deliver high calorie food in quantities that you and I couldn’t possibly eat to an individual on a daily basis. So there’s a moral issue,” he said.

“Some patients have feeders. They will have a relative or friend who will go to the supermarket or takeaway place and buy food for them to eat. There’s psychology, there’s genetics and, unfortunately, there’s no easy answer.”

Craig Sinclair, head of the Cancer Council Victoria’s prevention division, and spokesman for the Obesity Policy Coalition, said the problem could not be tackled if it was viewed as merely a “lifestyle choice”.

He said disadvantage and a lack of education were often drivers, as were environmental factors such as a lack of access to fruit and vegetables, particularly in rural and regional areas.

“We also need to look at menu labelling for fast food outlets, or taxation to make junk food more expensive. It could be creating physical environments that encourage more physical activity safely such as bicycle lanes, and making it safe for kids to walk to school.”

Bendigo Health executives estimate they could save $45 million and 25,000 hospital bed days a year if healthy eating and physical exercise programs such as the Cancer Council’s Live Lighter campaign were adopted widely throughout the region.

“We have very high calorie food, and we don’t exercise enough. The evidence now is quite clear that it’s the food intake that’s the primary problem,” Professor Savage said.

Lynne no longer has an appetite for fast food and prefers grilled fish, salad and fruit. She has no goal weight, but is excited about being able to go for a walk down the street – something she has not done for months.

“I’m looking forward to going home and visiting friends and even sitting out on the front veranda at home in the sunshine and the fresh air,” she said.

“I hope that people hear my story and get help before it’s too late. I just wanted to live to see my grandkids grow up.”

Follow Jill on Twitter