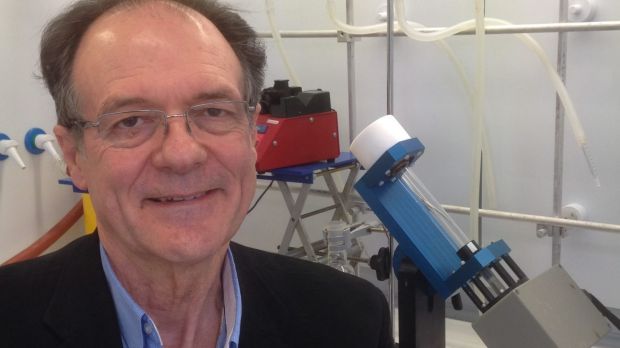

Professor Colin Raston with his invention, the vortex fluidic device, which can ‘uncook’ egg whites.

A machine invented by an Australian scientist that can “unboil an egg” by unfolding the proteins in egg whites back to their natural state has been hailed as a potential game-changer for the targeted delivery of chemotherapy drugs for cancer treatment.

The vortex fluidic device, invented by Professor Colin Raston? of Flinders University, uses mechanical energy by spinning molecules tremendously fast (up to 5000 revolutions per minute) to control chemical processes. Used on the cooked whites of eggs, the machine uncoils the albumen proteins returning them to their “natural” state making them active again in a clear solution.

The device can also be used to assist in the delivery of chemotherapy drugs, according to a report in the journal Scientific Reports, published on Friday by Nature.

The machine dramatically improves the attachment of the platinum-based cancer drug carboplatin to nano-sized delivery tubes called vesicles. Carboplatin works by binding to cancer cells, inhibiting their DNA synthesis and cell division. The authors of the paper expect that the use of nano-tubes for delivery will allow for a more targeted release of the chemotherapy drug.

Most cancer cells have a lower pH, or are more acidic, than normal, healthy cells, Dr Raston told Fairfax Media. By using the vesicles the carboplatin can be released more rapidly at lower pH levels. The study shows that 20 per cent of carboplatin was released after two days at a close-to-neutral pH of 7.4. At the more acidic pH of 5.5, 20 per cent of carboplatin was released from the vesicle within five hours – a 10-fold faster release rate.

The hope is that by releasing carboplatin? faster at lower pH levels, patients will be able to receive lower doses for more effective treatment.

Using Dr Raston’s machine, scientists were able to improve the efficacy of carboplatin attachment 4.5 fold to 75 per cent.

Dr Raston said that this is an important step towards targeted delivery of cancer treatments.

“By getting towards targeted delivery of cancer drugs you then need far less drugs to treat a patient,” Dr Raston said.

This also minimises drug waste. Up to half a tonne of manufacturing waste can be generated by the production of just one kilogram of anti-cancer drugs.

“Much of the drugs end up in the sewerage system and [could] create superbugs in our environment,” Dr Raston said.

Dr Ralston’s vortex fluidic device also has the potential to revolutionise the production of other pharmaceuticals by radically reducing the waste produced.

The device has already been shown to make biodiesel and is able to produce more stable – and hence “cleaner” – drugs. The stabilised molecules do not need to use purification processes, reducing waste.

The lead authors of the paper are Dr Raston and Professor Lee Yong Lim of the University of Western Australia.