An antibiotic-resistant “superbug” strain of typhoid fever is spreading worldwide, according to new research.

A study published in Nature Genetics conducted by a team of 74 researchers in over 12 countries shows that drug-resistant typhoid, driven by one family of bacteria called H58, is spreading globally.

“Multidrug resistant typhoid has been coming and going since the 1970s and is caused by the bacteria picking up novel antimicrobial resistance genes, which are usually lost when we switch to a new drug,” said study author Dr. Kathryn Holt. “In H58, these genes are becoming a stable part of the genome, which means multiply antibiotic resistant typhoid is here to stay.”

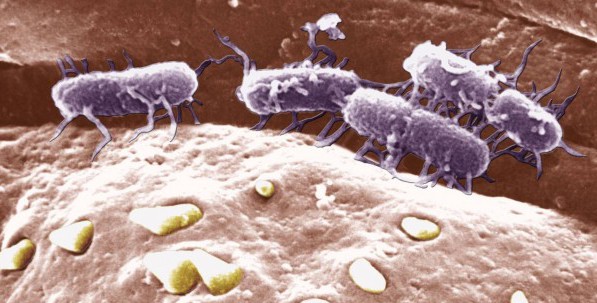

For the study, researchers sequenced the genomes of 1,832 samples of the Salmonella Typhi bacteria (which causes typhoid fever) that were collected from 63 different countries between the years 1992 and 2013. The researchers discovered that 47% of these strains were from the drug-resistant H58 family. According to their findings, the strain likely first emerged in South Asia roughly 30 years ago and from there spread on to Southeast Asia, Western Asia, East Africa and Fiji. Southern Africa has also been affected.

“H58 is displacing other typhoid strains, completely transforming the genetic architecture of the disease and creating a previously under appreciated and on-going epidemic,” the researchers said in a statement about their findings.

Typhoid fever is caused by consuming food or drink contaminated with the feces or urine of people who are infected. Symptoms include nausea, fever, abdominal pain and pink spots on the chest. If left untreated, the disease can lead to complications in the gut and head, which may prove fatal in up to 20 percent of patients.

Globally, an estimated 21.5 million people are infected with typhoid every year, leading to more than 200,000 deaths. About 5,700 cases are reported each year in the United States, mostly among travelers who became infected abroad.

Vaccines are available, although, due to limited cost effectiveness, not widely used in poorer countries where the disease is endemic. Instead, doctors have typically relied on antibiotics to treat the infection. But as The Guardian explains, “the broad usage of antibiotics has driven drug resistance in the organism, and as the H58 strain evolved and spread, it acquired resistance to frontline antimicrobials, and newer drugs too, such as ciprofloxacin and azithromycin.”

“This is one of the first pictures we’ve had of how antimicrobial resistance is impacting on the way we treat infectious diseases, and how we will have to tackle them,” Dr. Gordon Dougan, the study’s senior author, told The Guardian.

The findings paint a worrying scene of the “ever-increasing public health threat” of global antibiotic resistance, the researchers said. Currently, drug-resistant infections account for about 700,000 deaths around the world each year, but the problem is rapidly escalating. The World Health Organization said last year that bacteria resistant to antibiotics have already spread to every part of the world, and if left unchecked, will take us back to a “pre-antibiotic era” in which minor infections like strep throat could kill. By 2050, scientists predict that drug-resistant bacteria could kill as many as 10 million people annually.

In March, the White House announced a new initiative to combat antibiotic resistance with a series of measures that will crack down on over-use and over-prescription of antibiotics at farms and hospitals. It will also establish better surveillance and testing, which experts say is crucial for identifying new “hotspots” of resistance and tracking patterns over time.