The National Mental Health Commission’s exhaustive 2014 Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services was finally released last month after it was leaked to media including to Croakey.

The review raises a number of concerns about headspace, the national youth mental health foundation, which critics in this Sunday Age report said is failing vulnerable young people and has become the “McDonalds version of healthcare”.

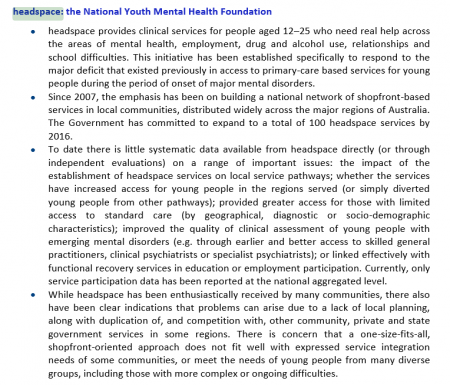

Issues and recommendations relating to headspace are contained in different sections of the review (best to search under its name in Vols 1 & 2), but here’s a sample (click twice on the image to enlarge):

Below are two articles in response to those concerns: from headspace CEO Chris Tanti and from youth mental health advocate Minto Felix. Tanti also argues against the Review’s recommendation that $1 billion in Commonwealth acute hospital funding be withdrawn and allocated to community-based psychosocial, primary and community mental health services, saying:

“My view is that more money needs to be put into acute beds, not less. The time has come for a more cohesive approach to mental health reform to reduce fragmentation and provide better services for people in need, but not one that relies as its key plank on taking money from one area to bolster another. Community-based early intervention services, such as headspace, and others are absolutely essential to support people in their communities. But we also need services for those people with serious mental health issues who require longer-term acute care.”

***

Chris Tanti writes:

It’s important in any conversation about the future of mental health in Australia, including the role of headspace, we focus on fact rather than opinion.

As a Commonwealth-funded organisation we welcome intense scrutiny about our performance and whether we are actually improving the lives of young Australians. This is a positive thing for our organisation and indeed the sector. Absolute transparency should be what is demanded when it comes to taxpayer funds.

The mental health sector is not a homogenous being. Debate about treatment and systems of care will benefit the community in the long term and it’s important, given the questionable history of some treatments in mental health that there is rigour and clarity. It might be a surprise to many, but not all of us agree on a way ahead and there are disparate views about the effectiveness of treatment, the benefits of intervening early and where we should invest.

The Mental Health Review recommended $1 billion in Commonwealth acute hospital funding be withdrawn and allocated to community-based psychosocial, primary and community mental health services. I have a problem with this. As the report states, the average stay in a public hospital bed for a person with an acute mental illness is nine to 11 days, and slightly longer in private hospitals. This is an appallingly inadequate amount of time for a person to receive the support they need to recover. My view is that more money needs to be put into acute beds, not less.

The time has come for a more cohesive approach to mental health reform to reduce fragmentation and provide better services for people in need, but not one that relies as its key plank on taking money from one area to bolster another. Community-based early intervention services, such as headspace, and others are absolutely essential to support people in their communities. But we also need services for those people with serious mental health issues who require longer-term acute care.

Equally important is ensuring that what all of us do is actually having an impact on the lives of people we are there to help. Over the last seven years headspace has invested heavily to get a good picture of the evidence of what we do and the efficacy of treatment. But when it comes to dealing with the various things that make the lives of our young people less than we would hope, every day headspace and the broader youth mental health community are getting a clearer picture of what works. We know early intervention is the key – dealing with issues before they become significant problems in a person’s life has been a long accepted approach in other areas of health such as cancer treatment.

There is significant accountability to government and data is reported on a quarterly basis. In addition to this, headspace is independently evaluated and the second such review is due to report in the next few months. I fully expect that the evaluation will have recommendations for further improvement – this is how quality health systems work. They evolve in response to critique and peer review and the latest science and evidence further enhances and advances what we do. It’s a fairly simple quality cycle and one that we actively participate in. This is something that for most part is missing from the mental health sector, so I agree wholeheartedly with the Mental Health Review’s recommendation for more rigour on outcomes and whether what we all do is working.

Many in the sector, including Ian Hickie and Pat McGorry, lament the lack of funding available for research and more needs to be done to address the shortfall for this in dedicated mental health research funding.

There are a myriad of services in the community working with young people and those with complex mental health problems. headspace, however, was not designed to duplicate services that already exist. headspace exists to fill a gaping hole in the system for young people who have traditionally been locked out of care, such as those with emerging problems who are not ‘unwell’ enough to come to the attention of the existing services. A third of our clients are not engaged in education, employment or training, and this requires a very nuanced and individual approach to support each young person in the most effective way.

Better integration and coordination of community services is what headspace is all about. Each headspace centre has its roots firmly planted in that community through a coming together of local leaders and community agencies, known as a headspace consortium. There are more than 600 local community organisations across the country involved in delivering headspace services to young people. The intention of this is to ensure the community agencies all swim in the same direction and run a local strategy that reflects the needs of the community that centre is located in.

headspace is not just a medical or psychiatric model of care. It borrows from other disciplines, including psychology (the largest part of our workforce) social work and the social sciences. It has a developmental focus on the needs of young people rather than a focus on illness or pathology, which is why it resonates so well with young people. We bring together services that address physical and mental health, work and study and alcohol and other drugs to provide a holistic approach that can deal with a range of issues a young person may be facing. And they only need to tell their story once.

headspace has noted the recommendations for the broader sector by the Mental Health Review, a lot of which we agree with. In fact, headspace has been in discussion with the Commonwealth Government for some time on ways headspace can be further strengthened and enhanced.. We do not shy away from informed discussions about how our service might be improved because ultimately built into our DNA is an authentic focus on those who we are here to serve.

***

Minto Felix writes:

There is no greater loss than that of a life. But that loss is particularly painful when it is self-inflicted and when a person, typically after a long period of suffering in silence, makes the choice to no longer be a part of our world.

I am only 22. But I have already encountered suicide in the communities I am a part of, three times. The loss of three people, who were cherished by their friends and family, and whose passing left their loved ones absolutely heartbroken. And perhaps the greatest tragedy in all of this – each of these individuals died well before their 25th birthday.

Yet, the chilling reality is that suicide remains the leading cause of death in young people, aged between 15 and 24. In 2013 alone, our nation lost approximately 350 young people. To put that into perspective, this was the size of my entire year level at high school. But of course, it’s not just young people – suicide takes the lives of seven Australians, every single day of the year.

I fundamentally believe that we can no longer accept the status quo.

To reduce suicides by half. This was the bold recommendation made by the National Mental Health Commission through its review of mental health services and programmes. Yet three weeks since the release of this report, we have heard nothing substantive from the Government about its response on this recommendation, and the many others that this report has made. We urgently need our political leaders to adopt this target, and work fervently to drive the strategies that will see a decrease in the numbers of lives lost.

Since the report, there has also been enormous debate within the mental health sector about the efficacy of different initiatives. Most notably, the performance of headspace – the National Youth Mental Health Foundation has come under great scrutiny. Is it reaching the most vulnerable young people in our communities? Are tax payer dollars being used in efficiently? And a statement that I am really troubled by – is headspace ‘corporatising’ mental health for young people in Australia?

Although 1 in 4 young people are estimated to experience mental ill-health, only 20% are able to actually access the help that they require. Further, recent research is highlighting that despite increased awareness of mental illness in our community, the significant proportion of young people still remain unsure about what professional support is effective and appropriate for them, making them less likely to seek support until their mental health significantly worsens. This clearly shows that there is a lot of work to do in empowering young people to have confidence in the services and treatment around them. This also clearly refutes the notion that mental health is becoming ‘corporatised’ for young people. If anything, the opposite is required – we need to significantly improve mental health literacy in our communities

The term corporatisation of youth mental health is an unhelpful term. At its core, headspace as a model, represents early intervention and primary care for young people presenting with emerging mental disorders – an approach that is highly consistent with research findings over the past few decades. This is the brand of headspace, and efforts directed towards strengthening this brand, can only be a good thing for young people in our communities. The term corporatisation also fails to acknowledge the enormous diversity in services and programmes provided by headspace centres all over the country, that are geared towards meeting the needs of the local communities in which they serve.

Whilst headspace isn’t without its flaws, it is the largest federally funded and dedicated provider of mental health services for young people in our country. Last year alone, the centres saw 54 000 young people, including a proportion of whom that accessed the service in relation to suicidal thoughts, as well as the vast majority that experience common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety. Though the causes of suicide are incredibly varied, and therefore the solutions equally complex, research consistently indicates that at the time of death, most individual are suffering from a recognisable psychiatric condition. Further, research also consistently highlights that early intervention is key to reducing the risk of suicide. As an early intervention service, headspace is the first and perhaps most important step, for a young person going through a really difficult time, to get the help that they so urgently require.

Over the last 10 years, headspace has transformed the way young people engage with their mental health in this country. The service has normalised experiences of becoming mentally unwell, but more importantly, it has improved the well-being of the hundreds of thousands of young people that have engaged with its services since its inception. Headspace has not corporatised, but mainstreamed, mental health for young Australians. And, if we are to halve suicide for young people in our country, then the services of headspace centres around the country must continue to play a critical role in this agenda for change.

Across the board, there is a sentiment that the recent mental health service review hasn’t highlighted anything new or surprising. We know the facts. And right across the community, we know the enormity of the challenge at hand. But we also know that change is entirely possible. For every day, that we spend forging solutions for a better future forward, we ensure that another young person is able to work through any difficulties that they come up against – and positioned to realise their fullest potential.

We must act now.

Minto Felix is a youth mental health advocate. He currently works on Leadership Projects at Monash University and as Head of Strategy at Collective Potential – working to improve the well-being of young people. You can follow him on Twitter @mintofelix.