Thinking can fire up nerves in the brain and can lead to the proliferation of brain tumors, according to new research from Stanford University.

The study, which was recently published in the journal Cell, found that tumors actually use nerve activity in the cerebral cortex — i.e., thinking — to promote their own growth.

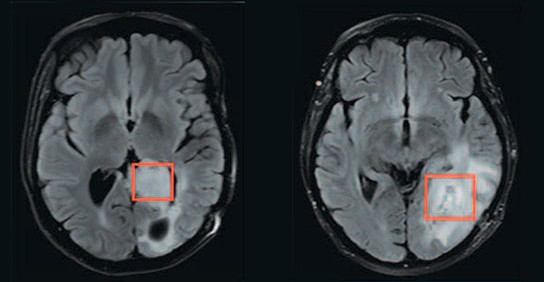

The researchers observed high-grade gliomas, a deadly form of tumor that starts in the brain or spinal cord, and makes up roughly 80 percent of malignant brain tumors. Currently, treatment options for high-grade gliomas are very limited.

The experiment, which was conducted on mice, was the first to show that brain activity can stimulate the growth of brain tumors. This is surprising, given that the function of other organs does not seem to drive tumor growth, noted the study’s author Dr. Michelle Monje, a researcher and neurologist at Stanford.

“We don’t think about bile production promoting liver cancer growth, or breathing promoting the growth of lung cancer,” Dr. Monje said in a statement. “But we’ve shown that brain function is driving these brain cancers.”

So how does it work? The researchers identified a protein in the brain, neuroligin-3, that in a healthy brain is involved in the growth of new synapses and the brain’s ability to rewire itself. Using optigenetics — a technique that uses genetic manipulation to insert light-sensitive proteins into specific neurons –the researchers showed that when a tumor is present, the protein promotes the growth of the tumor.

Theoretically, it could be possible to slow the growth of these tumors by using sedatives or other drugs to reduce mental activity, Dr. Monje told NPR. But that’s not a viable option, she explained, because it wouldn’t eliminate the tumor and “we don’t want to stop people with brain tumors from thinking or learning or being active.”

However, the findings could pave the way for new treatment options, possibly by interrupting the specific pathways linking brain activity to tumor growth.

“Clinically, fighting high-grade gliomas is a lot like trying to fight a forest fire,” said Dr. Monje, who is also a pediatric neuro-oncologist at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, where she cares for patients with these tumors. “Our new findings indicate that this metaphorical forest fire has been difficult to extinguish because there is something akin to gasoline seeping up from the soil.”