‘No matter how many facts are told, no matter how many details are given, the essential thing resists telling.’

This evocative quote is cited in the Croakey long-read below, which contains many fascinating insights into the issues surrounding the “unprecedented”, ongoing Ebola outbreak in west Africa, including the challenges of recovery and of public health messaging.

In the first part, Professor Tarun Weeramanthri, Chief Health Officer of the WA Department of Health, shares some reflections on the bumpy “road to zero”, from a two-month consultancy with the World Health Organisation, which included five weeks in Sierra Leone.

In the second part, virology blogger Dr Ian M Mackay and colleague Dr Katherine E Arden examine some of the lessons out of the Ebola epidemic, including the importance of human factors in contributing to the impacts. Their article is cross-posted from the blog, Virology Down Under.

***

As the tide turned – Ebola in Sierra Leone

Tarun Weeramanthri writes:

In January and February of 2015, I took two months leave from WA Health to work with the World Health Organisation (WHO) on the response to Ebola in West Africa.

Five weeks in Sierra Leone, and three weeks in Geneva, does not make me an expert on Sierra Leone, on Ebola or on WHO. What it did give me though was a window to observe a country, a public health response and an international organisation at a time of both crisis and transition.

Having not previously worked with the organisation, the opportunity arose through a personal approach from Ian Norton, an Australian colleague who moved to Geneva last year to set up a Foreign Medical Team (FMT) coordination capacity within WHO.

Over 10 years of work with Australian Medical Assistance Teams (AUSMAT) gave me some confidence to accept a short-term position as the FMT coordinator in Sierra Leone.

My motivations were mixed – personal/humanitarian and professional/civic. In some part, the work provided an outlet for the frustration that had built within me at the slowness of the response from Australia and the international community.

My motivations were mixed – personal/humanitarian and professional/civic. In some part, the work provided an outlet for the frustration that had built within me at the slowness of the response from Australia and the international community.

The facts of the Ebola epidemic are well known, but the reality is elusive. I am reminded of some lines from Paul Auster, ‘No matter how many facts are told, no matter how many details are given, the essential thing resists telling.’

Starting in December 2013, and formally recognised in March 2014, it was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in August 2014.

The first Ebola epidemic to occur in West Africa (previous outbreaks have been in Central and East Africa), the first to affect more than one country at the same time, the first to affect major urban areas, and the first where there has been transmission outside Africa, it fairly earnt the ‘unprecedented’ tag.

After the critical initial delay, the international response scaled up from around September 2014. It took until December for there to be sufficient Ebola treatment capacity to meet demand in Sierra Leone.

Rapid change

Preparing to leave Australia, the prospect was of a constant rise in cases. However, arriving in Freetown in the second week of January, the situation was changing rapidly and for the better. A few weeks earlier there had been over 500 cases/week in the country, and over January case numbers fell to under 100/week.

Suddenly there were more beds available than cases, and the goal of the response changed from stopping the rise (Phase 1) to ‘getting to zero’ cases (Phase 2). Epidemiologists started talking about the ‘halving time’ rather than the ‘doubling time’ of the epidemic.

There was strong leadership evident at the National Ebola Response Centre (run by the Ministry of Defence), at the Ministry of Health and at the WHO national office in Freetown. Some around the WHO table had, like myself, not previously worked for WHO, but the only thing that seemed to matter was whether you could perform your role.

The impact of the initial delays in international response was still evident in January 2015, with WHO staff numbers in country finally peaking in that month.

From the FMT coordination perspective, there had been 1-2 people employed doing understandably reactive tasks through late 2014, but by early 2015, there was a team of 6 who could create a set of roles, build a team culture and engage with the 32 foreign medical teams in a more structured fashion.

Approximately half the foreign medical teams were either funded or supported by national governments (including the Cuban Brigade, UK National Health Service and African Union), and half were international non-government organisations (including Medicins Sans Frontieres, Save the Children, Partners in Health, International Medical Corps, and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies).

Importance of trust and credibility

All the organisations had strong underlying values and missions, and a need to be accountable to their own funders and supporters. This fact, coupled with a failure to register the FMTs on arrival, and the limited WHO capacity in late 2014, meant that the FMT Coordination team needed to build trust and credibility quickly with the already well-established FMTs.

Our role was two-fold: to support teams and enhance the quality of care through training, clinical mentoring and incident review; and to contribute to planning through providing accurate information on quantity, quality and pipeline of foreign teams.

As case numbers declined, and bed occupancy fell, a subtle competition for patients emerged, with some treatment facilities (for confirmed cases) adding on and opening up holding centres (for triage and testing, suspect and probable cases). As the clinicians continued their work, the public health workers were identifying cases, following up contacts, and working with communities around prevention messages and safe burials.

The majority of staff (clinical, sanitation and support) in the 20 or so Ebola Treatment Centres were nationals, and they worked alongside foreign staff in integrated teams. They also constituted the majority of staff in holding centres and community care centres.

There were regular infection control incidents of concern that needed to be managed and investigated. Overall, since the start of the epidemic in Sierra Leone, there have been over 300 health care worker deaths from Ebola, but paradoxically the majority seem to have been infected, not in the treatment facilities, but in their own community caring for relatives and friends without personal protective equipment.

In addition, a number of foreign health care workers have been infected with the Ebola virus – almost all have been evacuated and recovered, in contrast to the high mortality for national health care staff treated in country. One foreign medical worker died of malaria.

Concern about “spotfires”

As case numbers fell, there was an urgent need to avoid complacency, maintain the momentum and push towards zero cases, as well as think about the requirements for non-Ebola care (which had largely collapsed in 2014) and post-Ebola care (including the retraining of staff and repurposing of Ebola treatment facilities).

The situation in neighbouring Liberia was improving faster than in Sierra Leone, but that served to highlight the importance of cross-border transmission, and the potential for re-introduction from another country or region. Like a bushfire, as the main fire came under control, the potential for spotfires to flare up was ever present. One senior WHO person described it ‘not as one, but 60, outbreaks’.

The impact of an Ebola epidemic on any country would be marked; in countries like Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, with high levels of poverty and poor infrastructure, how much more so. The consequences were visible: schools closed (many facilities had been used for Ebola treatment), businesses shut, organised sport cancelled, mass gatherings banned, and homes quarantined.

However, signs of resilience and community survival were also strong. Street schools had sprung up with volunteer teachers, soccer teams trained on the beach, there were still vibrant markets and people trading.

However, signs of resilience and community survival were also strong. Street schools had sprung up with volunteer teachers, soccer teams trained on the beach, there were still vibrant markets and people trading.

There were opportunities for providing accommodation and other services to the high numbers of foreigners, who were in the country to assist in the Ebola response.

The government was keen to re-open schools, but in a safe and planned manner, and attract future investment to help rebuild the country.

Everywhere there were signs reminding the population of the high numbers of Ebola survivors (well over a thousand), and newspaper articles urging acceptance of survivors, and an end to stigma. As the tide turned on the Ebola epidemic, such a recovery perspective became stronger and even more important.

And all the time, just under the surface for the people who experienced it, sits the background of a psychologically devastating civil war that ended in 2002. If you care to ask, a story of trauma or loss is only the next person away. After the civil war, there was a Truth and Reconciliation process, and war crimes trials. A Special Court was built for the trials, and in 2014 the premises were converted into the headquarters for the National Ebola Response.

We held our weekly FMT coordination meetings in a courtroom of the old Special Court; and in the grounds there is a Peace Museum, that aims to keep alive the historical record of the war and build a culture of human rights in Sierra Leone today.

The museum was closed with the outbreak of the Ebola epidemic, but the director is planning to open a garden of remembrance when he can. For me, that’s the whole point of responding to the Ebola epidemic – so that people can get on with their normal lives, and think about things other than Ebola. School, soccer, family gatherings, social change, whatever you’re into.

The final few weeks of my time away were back in WHO headquarters in Geneva. There I got to view the ‘convening power’ of the organisation. A three-day international FMT meeting was held with 150 people present from 88 organisations. The first two days focused on phase 2 of the Ebola response, with Ministry representatives from Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia prominent. The last day considered the next steps in the development of the overall FMT initiative.

At this point in its history, and partly as a response to criticism of its response to the Ebola outbreak, WHO has been charged with developing a modus operandi that is operational as well as technical. It has also been asked by member states to put forward ideas for a new Global Health Emergency Workforce that can be drawn upon quickly at times of crisis.

As I write, the ‘road to zero’ is proving, as predicted, bumpy. The rainy season is a couple of months away, and could hinder outbreak control if the epidemic continues till then. A lockdown has just ended. Sierra Leone, having sat at 50-80 cases/week for some weeks since late January, is showing signs of a further decline in cases. Liberia is ahead, and Guinea behind.

From a personal point of view, the experience was a good one. The basic skill-set of management, practised everyday in Perth, was also useful in Freetown. Handling people, information and resources is always going to be important in a coordination role. The fundamental difficulty lay in the overlay of fear, misinformation and stigma.

I was lucky enough to experience something different in WHO, where the leadership was strong, and the response rational, though of course, like all human activities, imperfect. I also met a number of local survivors, as well as two international healthcare workers, who had recovered from Ebola and returned to Sierra Leone to continue their work.

The ‘One Year after Ebola’ reports are starting to roll in but the epidemic is not yet over. We are all still in this together; all of us in public health, and all of us as human beings with similar day to day concerns.

Survival is the goal, and continued resilience a large part of the answer.

• Professor Tarun Weeramanthri is Chief Health Officer, Department of Health, Western Australia. You can also watch his presentation here.

*******

Catching Ebola: mistakes, messages and madness

Dr Ian M Mackay and Dr Katherine E Arden write:

Despite obvious community and media fear, speculation and exclamation that Ebola virus would enter and spread widely within countries outside the hot zone, such an event did not come to pass in 2014.

Despite obvious community and media fear, speculation and exclamation that Ebola virus would enter and spread widely within countries outside the hot zone, such an event did not come to pass in 2014.

The early public health messaging on Ebola virus and disease were, for the most part, spot on.

In 2014 and 2015, thousands of cases of Ebola virus disease (EVD) ravaged Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia in 2014 (the “hotzone”). A smaller outbreak was defeated in Nigeria [8] and another distinct Ebola virus variant drove an outbreak of EVD in the Democratic Republic of the Congo[7] – they too controlled spread of the virus.

Ebola virus travelled from the hotzone to other countries including Senegal, Nigeria, the United States of America (USA), Mali and most recently, the United Kingdom. It did this by hitching a ride in a usually unknowingly infected human host.

Over 40 people have been intentionally evacuated or repatriated for observation or more aggressive supportive care – and perhaps the use of experimental therapies – to France, the USA, Spain, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.[1,18]

Recently, the last country outside of Africa to have unintentionally acquired a case of EVD, the United Kingdom, passed a milestone; 42 days since the last ill patient tested negative for Ebola virus. They were declared free of known virus transmission.[17]

Containing the spread of each imported case has relied upon stringent infection prevention and control measures and the identification and monitoring of each and every contact of an Ebola virus infected person. And these have been used with great success.

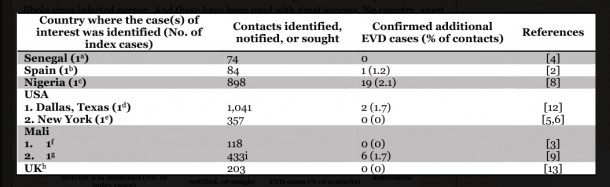

No country, apart from the three in which transmission has been widespread and intense, has seen the appearance of multiple and continuing rounds of new EVD cases. A rough calculation of the numbers of contacts falling ill from each EVD index case who travelled outside the hotzone is shown in the table. It only includes those with data available publicly.

On average, fewer than 1 in 100 contacts (0.8%) came down with EVD. Not the easiest virus to catch? If you compare that to measles, 9 in 10 non-immune people close to an infectious measles case will acquire disease (90%).[19]

| a-man travelled overland from Guinea while infected; b-man with EVD repatriated from Liberia; c-man who flew while symptomatic to Lagos, Nigeria with a stopover in Lome, Togo; d-man flew from Liberia while infected; e-male healthcare worker returned from Guinea; f-a 2 year old girl travelling overland while infected; g-male travelled by car to a clinic in Bamako, Mali from Guinea (assumed Ebola case); h-female healthcare worker returning from deployment in Sierra Leone; i-this figure may indicate all contacts for both Mali cases |

The extent of the fear inspired by the first imported EVD case was especially clear from the massive spike in social media content from the United States which followed the arrival from Liberia of an individual with EVD; far more social media activity than had been seen in the United States to that point, or since.[14,10]

This month, even though 11 contacts/associates are being flown back to the United States for observation; on the heels of the index case, social media activity has barely responded – in fact Twitter is possibly more positive/neutral about Ebola in the US in March 2015 than in August 2014, rather than excessively fearful, mean or just plain hysterical.[10]

Some of the heat may have been taken out of the emotional response to Ebola outside Africa because it is now clear that a catastrophic pandemic is not going to happen. Kinda like we were told. I know; it;s so uncool to be reminded that you were told something by a grown up – and it was right!

Well…THEY TOLD YOU SO!!!

Nations with better (some!) healthcare infrastructure, preparedness, healthcare to patient ratios and those who got advice and help quickly, curtailed the spread of EVD. Kicked it out. Stomped on it. Terminated it. This was true even when contacts had been classified as at high risk of getting sick.[15]

Public health messaging made some big calls early on. Some examples include tweets by Head of Public Relations for the WHO, Gregory Härtl, and later by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Director, Dr Tom Freiden.[11] They made it clear that Ebola virus was not easy to catch and that measures to stop an outbreak were known.[16]

At the time, this didn’t jibe with other voices and the unprecedented number of EVD cases and deaths, especially from August onwards, that were tallying up at an exponential rate in west Africa. But those messages, while technically correct, probably didn’t convey enough of some of the biggest factors in a disease outbreak – fear, ignorance (meant only in the sense of no specific knowledge of Ebola virus and EVD), tradition and history – the human factors rather than the viral ones.

Some comments about transmission suggested essentially no chance of even a single new case happening on the home soil of richer countries – they were overly enthusiastic. They were unjustifiable and when some hospital workers in non-African countries became infected, they were ultimately seen for the mistake in message crafting that they were.

Still much to learn

Much of the science of the Ebola epidemic is yet to be written, but what we know today is that it is unlikely that Ebola transmission is any different from what was observed decades ago. Direct, physical contact with a very ill person’s fluids is the overwhelmingly biggest risk factor to target in reducing disease spread. And even then there’s no guarantee that disease will result from all instances of contact. We still have much to learn.

What has changed since the bad old days? We’ve learned how to better manage and support EVD cases. EVD is a disease that caught us a little unawares in its combination of “skills” – it spreads by care and through direct contact, accrues a lot of virus in the blood but also vast quantities in explosively propelled fluids produced from “both ends”; virus that remains infectious for even longer in urine and semen than in blood. Quite the mix of issues to deal with.

EVD is no longer a death sentence, and this needs to become part of the new messaging paradigm. It’s a message that may still be highly relevant to those in Guinea and Sierra Leone who seemingly would still rather risk death than seek care at a treatment unit.

Post-mortem detection of EVD cases is ongoing, although may be on the decrease but also nearly a third of cases in Guinea and Sierra Leone are arising from unknown human sources.[21] Contextual communication is needed from within each country and region. That aspect cannot be allowed to wane.

With early care, and active care, rather than the palliative model that seemed to occur when the ratio of EVD cases to healthcare workers was too high, patients mostly survive. The EVD treatment center at the Hastings Police Training School near Freetown, Sierra Leone stands as a model for successful life saving and is the best described example of this from the west Africa epidemic to date.[20]

Ebola virus infection is not easy to catch, it can be survived much more often than was generally accepted and its spread can indeed be stopped. Stopping an Ebola outbreak quickly seems to be helped mostly by prior education, ongoing communication, forewarning and preparation but also needs ongoing surveillance, functional healthcare infrastructure, a range of experienced workers and all of that must all be under-written by money.

But even with all that help in place, mistakes will be made and lessons will be learned, by everyone, all the time. Embrace that. We’re all human.

• This article was first published on 18 March at the blog, Virology down under (VDU), which aims to break down and comment on complex stories and papers about viruses, with a focus on emerging viruses and respiratory viruses. But like a virus, it keeps mutating.

References

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/07/31/world/africa/ebola-virus-outbreak-qa.html

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/137510/1/roadmapsitrep_5Nov14_eng.pdf

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/ebola/20-november-2014-mali/en/

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/ebola/17-october-2014/en/

http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/pr/press-statements.shtml

http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/united-states-imported-case.html

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1411099

http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20920

http://www.symplur.com/blog/the-life-cycle-of-ebola-on-twitter/

http://www.foxnews.com/opinion/2014/08/09/truth-about-ebola-us-risks-and-how-to-stop-it/

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/20/us/cascade-of-contacts-from-ebola-case.html

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ebola-contact-tracing-underway

http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(14)62016-X.pdf

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/ebola/3-september-2014/en/

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/b/4a798222-3666-446d-81ff-f21412a3f068?cmpid=yhoo

http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/ebola_marburg_fevers/Pages/medical-evacuations.aspx

http://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/transmission.html

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc1413685

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/156273/1/roadmapsitrep_18Mar2015_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1

Ian M. Mackay completed his undergraduate studies in Medical Laboratory Science at the Queensland University of Technology. He obtained his PhD in virology from The University of Queensland (UQ) in 2003. He is currently an academic Associate Professor at the UQ in Brisbane, Queensland, a Section Editor at Biomolecular Detection and Quantification an Associate Editor at the Journal of Clinical Virology and an Editor at Viruses. His overarching goal has been to understand viruses that infect animals and humans. His interests encompass respiratory viruses (particularly coronaviruses, influenza viruses and the picornaviruses), virus:virus interactions, virus detection and discovery, emerging viruses, teaching, writing, creating and correcting typos and leveraging social media to inform and educate himself and others about virology.

Katherine E. Arden obtained her PhD entitled Control of Replication of HIV-1, from the University of Queensland (UQ) in 1999. She has completed postdoctoral research including promoter studies of ion channels in the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, UQ; trafficking of iron-related proteins in haemochromatosis at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research; and the detection, culture, characterisation and epidemiology of respiratory viruses while working at the Qpid laboratory, Sir Albert Sakzewski Virus Research Centre. She is currently working part time for a grant readership scheme, while gaining greater hands-on experience of respiratory viruses from her children.