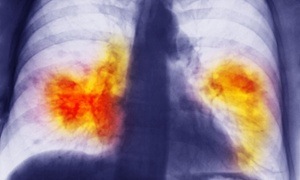

She was only 50 but a lifetime of smoking had exacted a significant toll. Some months ago she was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer when a suspected infection failed to resolve. She said at the time that her main feeling was anger because nobody in her smoking group had ever been sick. She was determined to fight the cancer but her breathlessness worried me from the start. She couldn’t walk down a flat corridor without gulping for air. Correcting her anaemia and draining two litres of fluid from her lung helped her attain her goal of starting chemotherapy. Would the chemotherapy save her, a daughter had asked. It might help improve quality of life, I had answered honestly, but given her condition I wasn’t optimistic about extending survival.

Two types of chemotherapy had not helped. Despite the scan report mentioning stable disease it was clear that her disease burden was large and her overall condition in decline. What next, she asked on her second last visit. Supportive care, I thought. Keeping her symptoms at bay with morphine, oxygen and an admission to hospice if required. But it wasn’t what she had in mind.

“I have heard there is this new pill for lung cancer.”

Belonging to a new class of blockbuster drugs, the tablet had indeed been approved for a subset of lung cancer patients. While she qualified on paper her condition made it unlikely that she would benefit from it. But to her feelings of anger and betrayal she had now added adamant resolve.

“I want that pill.”

“I don’t think it will help you and it might actually backfire,” I explained, providing examples of how unforeseen toxicities hastened decline.

“It’s worth a try,” she insisted, eventually leaving with a prescription and apparently jubilant at her victory.

Just a week later, she landed in emergency. Barely conscious, she looked gaunt and defeated. The hushed whispers of her family mingled with the hiss of continuous oxygen. She died just as I took her hand, having survived almost exactly six months from diagnosis, a typical life expectancy for those who don’t receive any chemotherapy.

I sensed palpable relief that her suffering had come to an end and the event would have been fairly routine but for my glance that wandered to the ledge. There, still unopened, was the box of tablets she had persuaded me to prescribe.

“She couldn’t be bothered opening it,” her husband said, handing it over.

I turned the precious contents in my hand.

“Can you give it to someone else?”

“No. It will be discarded.”

“I guess it was another $6 gamble,” he shrugged apologetically.

I looked away to hide my dismay. The concessional price to the patient was $6.10 (£3.19) but staring at me accusingly was the actual price tag in fine print, over $1,200 (£628) for a month’s supply.

Gamble was a generous description – I had prescribed a highly expensive drug to a patient knowing that it would result in neither survival benefit nor symptom control. As a public hospital employee I had no financial motive but felt cornered by a desperate patient. Or had I? Insistent patients can be gently persuaded to eschew harmful treatments and on occasions I have flatly declined to prescribe chemotherapy to very frail patients.

Perhaps lurking inside me was a fleeting hope that the drug would reverse the ravages of disease albeit temporarily. Or maybe I was drawn to the promise of being the oncologist who never gave up. Maybe I didn’t want to consign a patient to an early death – after all, oncologists and their misguided prognoses make for legendary stories. Or perhaps I had thought that if the drug was on a formulary it wasn’t my place to ration it. But none of this felt like a complete explanation.

My exasperation grew when someone asked, “If you knew it was so costly why didn’t you just say no?”

A common frustration with oncologists centres on their seeming inability to distinguish between cost-effective and futile therapies. On the one hand we argue for better access to newer and costlier drugs for our patients, on the other, most of us have prescribed one of these drugs without expectation of clear benefit. Some drugs hailed as a breakthrough live up to their promise but many don’t, especially when results of highly selective trials are applied indiscriminately to broad populations.

Australian government spending on chemotherapy rose from $84m (£44m) in 2009-10 to $586m (£307m) last financial year. The 63% annual growth in the cost of cancer drugs far exceeded that of other medicines, including those dispensed in public hospitals to manage other complex diseases. I understand why an onlooker might denounce the prodigal oncologist but I really think that you have to be inside one of these consultations to appreciate how fraught they are.

Every conversation about cancer occurs in an atmosphere of fear and vulnerability. Anger and betrayal, hope and resignation are always circling. Just as my patient had researched the new pill, she understood her terrible prognosis. But it didn’t stop her from hoping for miracles and it didn’t stop her from beseeching me to help her live another week, another month, whatever I could manage, as if I alone controlled her fate.

In theory her distress should not have swayed my objectivity and I should have calmly channelled her pleas into useful interventions such as palliation. But what is medicine if not the most human of endeavours? It is governed by evidence but made richer by emotions that just can’t be distilled into a tidy statistic.

In taking ownership of our patients we swim with their fears. I could have said a dozen times that the new drug was both futile and expensive but all she would have heard was that she was not worth it. Imagine conveying that notion a few times a week and going home detesting that kind of power over patients while wondering what if you got it wrong.

On that day, given that particular set of circumstances, I couldn’t say no to my patient but when she died, I felt awfully complicit in the misuse of precious public funding. Bureaucrats must shake their heads at people like me but frankly we all take turns at being that oncologist.

With hundreds of molecular therapies competing to reach the market, the uncomfortable subject of discussing the real cost of drugs with patients looms large over us. Yet it is conspicuously absent from medical training and public debate. Thus, every discussion about a “miracle” drug, marginally beneficial and ridiculously expensive, feels like a new experiment.

And the thing about medicine is that just as you feel you have got the right mix of compassion and objectivity you discover that the bitter pill you have been dispensing has suddenly become yours to swallow. The recent lament of a colleague perfectly encapsulates this dilemma.

“As an oncologist I find that many of the newer therapies are an unjustifiable expense on the public purse but when my father lay dying I can tell you that I wanted him to have every single one of them and didn’t rest till he did.”