The little voice inside your head that tells you to eat, or stop eating, isn’t a little voice — it’s actually a cluster of about 10,000 specialized brain cells. And now, an international team of scientists has found tiny triggers inside those cells that give rise to this “voice,” and keep it speaking throughout life.

The new research, done in fish and mice, can’t yet be applied to humans who eat too much or too little. But it reveals how tiny bits of DNA can have a big influence on how the body regulates appetite and weight. It’s the first documentation of exactly how a brain cell gene involved in weight regulation is controlled.

In a new paper published online this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and a recent paper in PLoS Genetics, the team reports their discoveries on genetic factors key to the brain cells, or neurons, called POMC cells.

Located deep inside the brain, in a structure called the hypothalamus, the cluster of POMC neurons act as a control center for feelings of fullness or hunger. They take in signals from the body, and send out chemical signals to regulate appetite and eating.

When POMC neurons are absent, or not working correctly, animals and humans grow dangerously obese. Now, the new findings show in animals that the same thing happens when certain genetic triggers inside the POMC cells aren’t working.

The team, led by Malcolm Low, M.D., Ph.D. of the University of Michigan Medical School and Marcelo Rubinstein, Ph.D., of the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina, has studied the POMC system for years.

Their new findings center on the gene inside the cells that generates the appetite-regulating signals — the Pomc gene, short for proopiomelanocortin. But studying the gene itself doesn’t tell the whole story of why and how POMC cells do what they do.

In the two new papers, the team reports how a protein called a transcription factor, and two small stretches of DNA called enhancers, act as triggers for the Pomc gene. All three regulate how often and when the POMC cells use the gene to create the signal molecules that then go out to the body. The transcription factor, called Islet 1, also plays a key role in helping POMC cells form correctly during the earliest stages of the brain’s development, before birth.

“The POMC region is a central node of the brain’s means for regulating body weight, in response to influences from the hormone leptin,” says Low, a professor in the Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology. “We’re interested in understanding how the Pomc gene is regulated in these neurons, which are a very small population with a big job.”

Probing gene triggers

The discovery reported in PLoS Genetics shows the impact of two different gene enhancers — stretches of DNA near the Pomc gene that make it easier for the cell to read it. Like signal lights that show pilots the path to an airport runway, enhancers guide proteins toward the gene so it can be read.

The researchers found that the two enhancers act in ways that complement one another, both encouraging the expression of the Pomc gene at key times. One of the two is found in the same form among all mammals, the other among all placental mammals — suggesting that they’ve been kept intact throughout the evolutionary process.

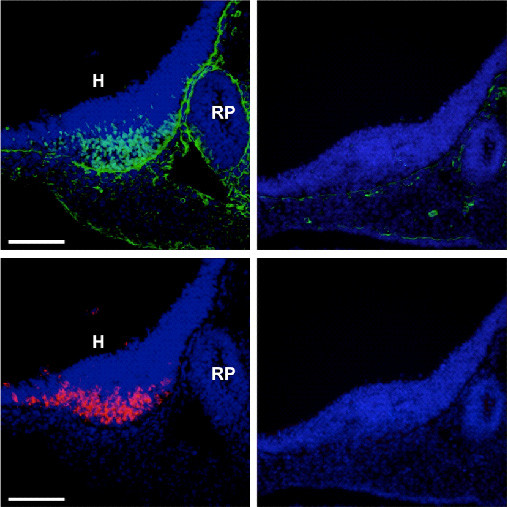

The new research shows the enhancers, called nPE1 and nPE2, specifically regulate the Pomc gene only in the brain. Mice born without both of them became obese — as if their Pomc gene had been deactivated. Meanwhile, mice that just lacked nPE2 grew normally, as the presence of nPE1 compensated.

The redundant enhancer system for Pomc suggests the gene’s importance, Low says. But when it comes to understanding what triggers a cell to read a gene, gene enhancers are only part of the equation. The protein that latches on to the enhancer, called a transcription factor, is also vital.

In the new PNAS paper, the researchers report that the transcription factor Islet 1, encoded by the Isl1 gene, plays this important role for Pomc. As its name suggests, Islet 1 plays a transcription factor role in the islet cells of the pancreas, which make insulin to help the body process sugar from food.

But, it turns out, it also plays this role in POMC cells. When the researchers blocked cells of the hypothalamus from making Islet 1 halfway through pregnancy, the fetal mice failed to develop any POMC cells. Moreover, when they allowed mice to make Islet 1 normally in the hypothalamus before birth, then blocked it, the amount of POMC was markedly reduced and obesity resulted.

The researchers were also able to show the importance of Islet 1 in zebrafish, which also fail to develop POMC neurons when the transcription factor was blocked early in development. Since zebrafish use different gene enhancers to regulate the reading of the Pomc gene, this shows the true importance of Islet 1 by itself.

“Taken together, this work represents the first example of a neuron-specific gene in vertebrates where we have found both the enhancers and a shared transcription factor that control gene expression in the developing brain and then throughout the life span of the adult,” says Low.

Future directions

Studying the impact of a total loss of Islet 1 or one or both of the two Pomc gene enhancers in animals showed the importance of these triggers, he says. But looking to see if the same factors do the same thing in humans will be more complex — and there may be other enhancers and transcription factors involved.

So far, genome-wide studies of humans have not shown any relationship between obesity and changes in the Isl1 gene. Brain imaging that tracks the binding of signals to and from POMC cells could reveal further clues. And in theory, it could be possible to find drugs to increase the production of Pomc gene products, or to grow replacement cells for malfunctioning POMC cells.

“For humans, Pomc regulation may be part of the equation of weight control,” says Low. “We don’t know, but we think it likely, that it may be similar to the mouse model, where its role is like a dial, with a linear relationship between the amount of Pomc expression and the degree of obesity. This research opens up our overall understanding of how the brain works to regulate feeding.”

Low and Rubinstein just received a new National Institutes of Health grant to continue their POMC cell work. They hope to look for other transcription factors, and to examine the roles of leptin and estrogen in stimulating POMC cells. They also hope to use neurons grown from induced pluripotent stem cells to study genetic activity during POMC cell development. And they’ll study POMC activity in mice that are pregnant or nursing, when POMC expression goes down and feeding increases.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by University of Michigan Health System. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

Journal References:

- Sofia Nasif, Flavio S. J. de Souza, Laura E. González, Miho Yamashita, Daniela P. Orquera, Malcolm J. Low, Marcelo Rubinstein. Islet 1 specifies the identity of hypothalamic melanocortin neurons and is critical for normal food intake and adiposity in adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2015; 201500672 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1500672112

- Daniel D. Lam, Flavio S. J. de Souza, Sofia Nasif, Miho Yamashita, Rodrigo López-Leal, Veronica Otero-Corchon, Kana Meece, Harini Sampath, Aaron J. Mercer, Sharon L. Wardlaw, Marcelo Rubinstein, Malcolm J. Low. Partially Redundant Enhancers Cooperatively Maintain Mammalian Pomc Expression Above a Critical Functional Threshold. PLOS Genetics, 2015; 11 (2): e1004935 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004935