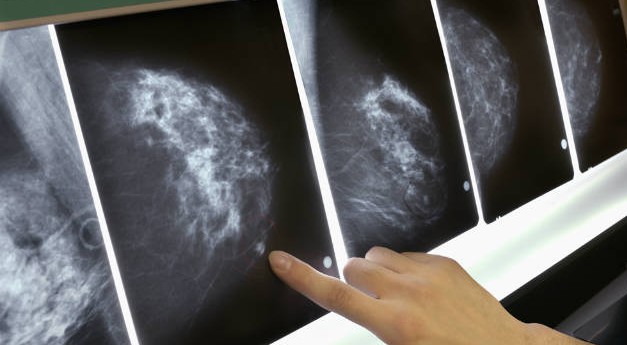

A new report from a group of leading medical experts in the U.S. says that breast cancer is not a single disease — rather, it consists of four molecular subtypes, each with different treatment responses and different survival rates. Incidence of these subtypes varies by age, race/ethnicity and many other factors, according to the experts.

The report, recently published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, was compiled by researchers from the North American Association of Cancer Registries (NAACCR), the American Cancer Society, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

The authors of the report, including Betsy A. Kohler of the NAACCR, say that defining breast cancer by the four subtypes will aid breast cancer diagnosis and treatment and help patients better understand how their diagnosis will affect their health.

After skin cancer, breast cancer is the most common cancer among American women. This year, it is estimated that 231,840 new cases of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in the US and more than 40,000 women will die from the condition.

For their report, Kohler and colleagues analyzed the incidence of invasive breast cancer in 2011 among women aged 85 and younger using data from NAACCR member registries.

These registries already record breast cancer incidence by four tumor subtypes, which are defined by the hormone receptor (HR) status and the expression of the HER2 gene. The subtypes are: Luminal A (HR+/HER2-), Luminal B (HR+/HER2+), HER2-enriched (HR-/HER2+) and triple-negative (HR-/HER2-).

Triple-negative breast cancer most common among non-Hispanic black women

Using this data, the researchers were able, for the first time, to examine how incidence of each breast cancer subtype varies by a number of factors.

For example, the report reveals that the least aggressive breast cancer subtype, HR+/HER2-, was most common among non-Hispanic white women. For each racial/ethnic group, rates of this subtype reduced as poverty levels rose, the team found.

Looking at the results by age, the team found that HR+/HER2- breast cancer rates were comparable across all racial/ethnic groups for women under the age of 45. Incidence of this subtype for women aged over 45, however, was more common among non-Hispanic white women than other ethnic/racial groups.

The researchers found that the most aggressive breast cancer subtype, HR-/HER2-, was most common among non-Hispanic black women. This is consistent with other recent data on breast cancer incidence among black women.

Non-Hispanic black women also had the highest rates of late-stage breast cancer diagnosis across all subtypes, as well as the highest rates of poorly/undifferentiated pathology. All of these factors are associated with poorer breast cancer survival, the team notes, which explains why black women have the highest rates of breast cancer deaths.

Dr. Harold Varmus, director of the NCI, says the fact this report assesses breast cancer as “four molecularly defined subtypes, not a single disease” is a “welcome step, depending on medically important information that already guides therapeutic strategies for these subtypes.” He adds:

“Further, it is a harbinger of the more rigorous classification of cancers based on their molecular features that is now being aggressively pursued under the President’s Precision Medicine Initiative.

The new diagnostic categories now being defined will increasingly support our ability to prevent and treat breast and many other kinds of cancer, as well as monitor their incidence and outcomes more rigorously over time.”

Cancer mortality rates down overall

In addition to analyzing breast cancer incidence in the U.S. by subtype, the researchers used NAACCR data to assess incidence and death rates of some of the most major cancers in the US and all cancers combined.

They found that between 2002 and 2011, overall cancer incidence rates fell by 0.5% annually. Between 2007 and 2011, overall cancer incidence rates for men fell by 1.8% every year. Such rates remained stable for women between 1998 and 2011, while cancer incidence rates among children have increased 0.8% annually over the past 10 years.

There was some good news in relation to overall cancer mortality trends: the team found that cancer death rates have fallen since the early 1990s. Between 2002 and 2011, overall cancer mortality rates fell by 1.8% annually for men and 1.4% annually for women. For children and adolescents aged 19 and under, cancer mortality rates have been falling since 1975, excluding the period 1998-2003.

“The continued decline in cancer death rates among men, women and children is encouraging, and it reflects progress we are making in cancer prevention, early detection and treatment,” says Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the CDC. “However, the continuing high burden of preventable cancer, and disparities in death rates among races and ethnicities, show that we still have a long way to go.”

In addition, the report reveals that there has been a fall in lung cancer and colorectal cancer incidence rates in both men and women, which the researchers say is likely down to reduced smoking rates as a result of public health interventions.

The report also identifies an increase in incidence rates for thyroid and kidney cancers, however, as well as a rise in incidence and mortality rates for liver cancer.

“The drop in incidence in lung and colorectal cancers shows the lifesaving impact of prevention,” says John R. Seffrin, PhD, chief executive officer of the American Cancer Society. “But we have a long way to go, not only in these two cancers but in the many other cancers where the trend has not been so positive.”