Over the next 35 years, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis will kill 75 million people and could cost the global economy a cumulative $16.7 trillion – the equivalent of the European Union’s annual output, a UK parliamentary group said on Tuesday.

If left unchecked, the spread of drug-resistant TB superbugs threatens to shrink the world economy by 0.63 percent annually, the UK All Party Parliamentary Group on Global Tuberculosis (APPG TB) said, urging governments to do more to improve research and cooeration.

“The rising global burden of multidrug-resistant TB and other drug-resistant infections will come at a human and economic cost which the global community simply cannot afford to ignore,” said economist Jim O’Neill, who was appointed last year by British Prime Minister David Cameron to head an exhaustive review on antimicrobial resistance.

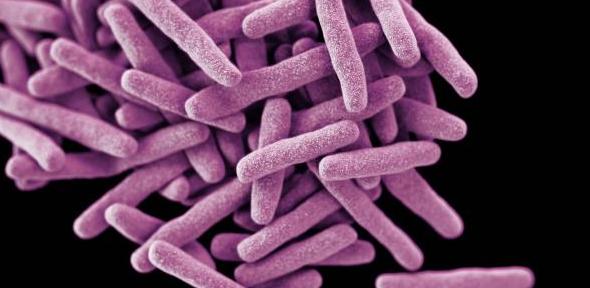

Like other infectious pathogens, the bacteria that cause TB can develop resistance to drugs used to cure the disease. Multidrug-resistant TB fails to respond to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, the two most powerful anti-TB drugs, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Drug resistance is a manmade problem caused by regular TB patients given the wrong medicines or doses, or failing to complete their treatment, which is highly toxic and can take up two years. A patient who develops active disease with a drug-resistant TB strain can transmit this form of TB to other individuals, thereby hastening its global spread.

Last year, the WHO warned that multidrug-resistant TB was at “crisis levels,” with about 480,000 new cases in 2013. Drug-resistant strains now account for a third of all deaths from the disease.

Global prevalence of multidrug-resistant TB (darker colors represent more cases)

The UK parliamentary group’s new cost projections are based on a scenario in which an additional 40 percent of all TB cases are resistant to first-line drugs, leading to a doubling of the infection rate. The group urged governments to set up a research and development fund, target investments into basic research and increase support for bilateral TB programs.

“We need better tools to deal with this new threat, but since TB primarily affects the poorest and most vulnerable in society, there is little commercial incentive to develop new drugs,” said Nick Herbert, co-chairman of the APPG TB.

The fight against TB, the world’s second deadliest infectious disease after HIV, is also hampered by a lack of an effective vaccine, the APPG TB said. The only TB vaccine, BCG, protects some children from severe forms of TB – including one that affects the brain – but is unreliable in preventing TB in the lung, which is the most common and infectious form of the disease.

TB, which spreads through the coughs and sneezes of an infected person, killed 1.5 million people worldwide in 2013, according to the WHO. Alarmingly, patients today have the same chance of surviving multi-drug-resistant TB with treatment as they have of surviving the Ebola virus without any treatment.

With antibiotic resistance on the rise, scientists have warned that drug resistant infections could kill 10 million people annually by 2035 — more than all types of cancer, combined.