Less than two weeks ago, exasperated and stunned, I joined with many other scientists, business leaders and leading science and research organisations to throw up my arms at the folly of the federal government threatening to mothball parts of our national research infrastructure (NCRIS).

Rarely have I seen so much angst from the scientific community. But also rarely have I seen such an energised and united rallying around a single science policy issue. Cutting NCRIS wasn’t just one more cut to the science budget; this was a dumb and nonsensical proposal to simply let support for the major research facilities dry up.

With Education Minister Christopher Pyne holding out until the last minute, it was a real surprise to see him pull back from the brink and release the funding for NCRIS for another year.

While this is a temporary reprieve, the scientific and research community, and those who support it, can’t lose sight of the main game. This is to find a lasting solution to securing support for our big research infrastructure. We can’t afford complacency because nobody wants to be back in this same situation again in another year’s time.

Long term view

The scientists who rely on our major facilities can now get back to doing what they do best: outstanding science. The prospect of becoming an embarrassment within the international science community has been averted, at least for a while. So what next for the future of NCRIS and research infrastructure?

Last year the Minister for Education commissioned a review of research infrastructure headed by Philip Marcus Clark AM, and this review is expected to report sometime around August 2015.

I’m counting on this report to demonstrate that our large research infrastructure is an essential part of the Australian science ecosystem. I am also expecting that the report will recognise the need for robust long-term planning that is critical for pieces of equipment with operating lifetimes of 10 to 20 years.

The only viable approach is that part of the Australian Government’s investment in science, each and every year, needs to be ear-marked for research infrastructure: its building; its maintenance; upgrading; and operation.

The annual funding scramble for NCRIS has really diverted our attention away from strategic thinking on research infrastructure. The Clark report is an opportunity for us all to turn our attention to the question of what infrastructure we actually need into the future.

The report will provide an opportunity to kick-start an ongoing process to identify emerging infrastructure needs, what infrastructure has reached its use-by date and is ready to be retired, and what new infrastructure needs to be built up and where.

I am also counting on the Clark report to recommend more sensible coordination of our major facilities. At present, NCRIS as a scheme sits under Minister Pyne in Education.

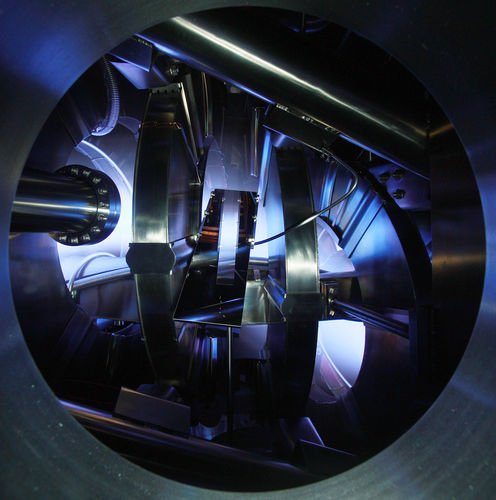

Other large slabs of infrastructure (telescopes, the Australian Synchrotron, ocean-going research vessels, etc) sit under Minister Ian Macfarlane as Minister for Industry and Science. It would clearly be better for all of the big research infrastructure to be in the one place with one responsible Minister and where the planning, monitoring and coordination can happen more effectively.

Better advocacy

NCRIS is a great initiative that has served Australia well and has positioned us to support our research effort and underpin the next generation of industries. NCRIS has been supported by both sides of government over the years since its inception a decade ago.

However, since 2010 the debate on research infrastructure in Australia has been dominated by impending funding cliffs with governments of both political persuasions unwilling to bite into the difficult decision of finding a long-term solution. Long term commitments which transcend the average lifetime of any government have always been hard issues to get traction on.

I hope that the lessons of the last few weeks, along with the outcomes from the Clark review, will allow us to respond to the insightful points made by Catherine Livingstone, Chair of the Business Council of Australia, on how we have found ourselves in such a sorry mess:

We have to see this as a failing on the part of the research sector, including universities, and on the part of business.

Our collective lack of advocacy over time, and

Our inability to promote the importance of knowledge infrastructure and the role of these research facilities.

Yes, we do need to take a strong message to Canberra – quickly, loudly, and in unison – if we are to secure a funding solution for research infrastructure. The case for investing in research infrastructure, and indeed science more broadly would be much easier if science enjoyed a similar profile with the public as say health, education or social services.

Unless the scientific community and its supporters want to find themselves back in Canberra a few months later trying to deliver the same message about some other important area of science under threat, or in need of investment, then we all need to do something differently.

We need to demonstrate the value of investment in science to the Australian people.

Les Field does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.