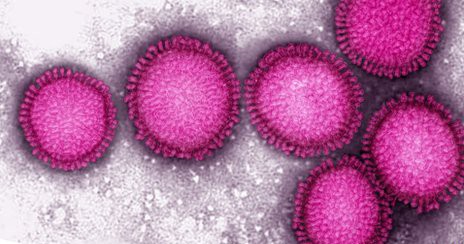

Since December, an outbreak of swine flu in India has killed more than 1,700 people, and a new MIT study suggests that the strain has acquired mutations that make it more dangerous than previously circulating strains of H1N1 influenza.

The findings, which are published online ahead of print in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, contradict recent reports from Indian health officials that the strain has not changed from the version of H1N1 that emerged in 2009 and has been circulating around the world ever since.

With very little scientific data available about the new strain, the MIT researchers stress the need for better surveillance to track the outbreak and to help scientists to determine how to respond to this influenza variant.

“We’re really caught between a rock and a hard place, with little information and a lot of misinformation,” says Dr. Ram Sasisekharan, a biological engineering professor at MIT and the paper’s senior author. “When you do real-time surveillance, get organized, and deposit these sequences, then you can come up with a better strategy to respond to the virus.”

In the past two years, genetic sequence information of the flu-virus protein hemagglutinin from only two influenza strains from India has been deposited into publicly available influenza databases, making it difficult to determine exactly which strain is causing the new outbreak, and how it differs from previous strains. However, those two strains yielded enough information to warrant concern, says Dr. Sasisekharan.

For the study, he and Dr. Kannan Tharakaraman, a research scientist in MIT’s Department of Biological Engineering, compared the genetic sequences of those two strains to the strain of H1N1 that emerged in 2009 and killed more than 18,000 people worldwide between 2009 and 2012.

The researchers found that the recent Indian strains carry new mutations in the hemagglutinin protein that are known to make the virus more virulent (aggressive). Hemagglutinin binds to glycan receptors found on the surface of respiratory cells, and the strength of that binding determines how effectively the virus can infect those cells.

One of the new mutations is in an amino acid position called D225, which has been linked with increased disease severity. Another mutation, in the T200A position, allows hemagglutinin to bind more strongly to glycan receptors, making the virus more infectious.

‘Aggressive surveillance’

Dr. Sasisekharan says more surveillance is needed to determine whether these two specific mutations are present in the strain that is causing the current outbreak, which is most prevalent in the Indian states of Gujarat and Rajasthan and has infected nearly 30,000 people so far.

“The point we’re trying to make is that there is a real need for aggressive surveillance to ensure that the anxiety and hysteria are brought down and people are able to focus on what they really need to worry about,” says Dr. Sasisekharan. “We need to understand the pathology and the severity, rather than simply relying on anecdotal information.”

With an unusually high fatality rate and increased reports of drug-resistant cases in this outbreak, some experts have voiced concerns that the virus may have already become more aggressive. Indian health officials, however, have repeatedly stated that the strain has not undergone “any major mutation,” and, upon release of the new study, immediately disputed the findings.

While the study was focused on this year’s seasonal flu, Dr. Sasisekharan says the results could also have important implications for future flu seasons. Learning more about the new strains could help public health officials to determine which drugs might be effective and to design new vaccines for the next flu season, which will likely include strains that are now circulating. “The goal,” says Dr. Sasisekharan, “is to get a clearer picture of the strains that are circulating and therefore anticipate the right kind of a vaccine strategy for 2016.”

In a separate study published just last week in the journal Nature, researchers reported that the H7N9 strain of avian flu is rapidly swapping genes with other types of flu viruses, giving rise to entirely new strains of influenza and increasing the likelihood that the virus will acquire a dangerous mutation. The H7N9 strain has already seen mutations that allow the virus to spread from birds to humans more easily than avian H5N1 flu; additional mutations could increase its ability to spread between humans or make it more aggressive. “H7N9 viruses should be considered as a major candidate to emerge as a pandemic strain in humans,” the researchers said.

Earlier this month, the World Health Organization issued a report warning that the world is “highly vulnerable” to a severe flu pandemic. The WHO said it is particularly concerned about avian influenza, noting that the diversity and geographical distribution of influenza viruses currently circulating in wild and domestic birds are unprecedented.