Modern life, with its preponderance of inadequate exposure to natural light during the day and overexposure to artificial light at night, is not conducive to the body’s natural sleep/wake cycle.

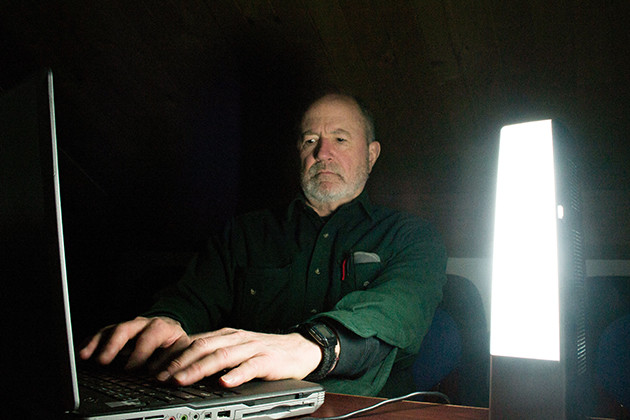

It’s an emerging topic in health, one that UConn Health (University of Connecticut, Farmington, Conn.) cancer epidemiologist Richard Stevens has been studying for three decades.

“It’s become clear that typical lighting is affecting our physiology,” Stevens says. “But lighting can be improved. We’re learning that better lighting can reduce these physiological effects. By that we mean dimmer and longer wavelengths in the evening, and avoiding the bright blue of e-readers, tablets and smart phones.”

Those devices emit enough blue light when used in the evening to suppress the sleep-inducing hormone melatonin and disrupt the body’s circadian rhythm, the biological mechanism that enables restful sleep.

Stevens and co-author Yong Zhu from Yale University explain the known short-term and suspected long-term impacts of circadian disruption in an invited article published in the British journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

“It’s a new analysis and synthesis of what we know up to now on the effect of lighting on our health,” Stevens says. “We don’t know for certain, but there’s growing evidence that the long-term implications of this have ties to breast cancer, obesity, diabetes, and depression, and possibly other cancers.”

As smartphones and tablets become more commonplace, Stevens recommends a general awareness of how the type of light emitted from these devices affects our biology. He says a recent study comparing people who used e-readers to those who read old-fashioned books in the evening showed a clear difference — the e-readers showed delayed melatonin onset.

“It’s about how much light you’re getting in the evening,” Stevens says. “It doesn’t mean you have to turn all the lights off at 8 every night, it just means if you have a choice between an e-reader and a book, the book is less disruptive to your body clock. At night, the better, more circadian-friendly light is dimmer and, believe it or not, redder, like an incandescent bulb.”

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by University of Connecticut. The original article was written by Chris DeFrancesco. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

Journal Reference:

- R. G. Stevens, Y. Zhu. Electric light, particularly at night, disrupts human circadian rhythmicity: is that a problem? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2015; 370 (1667): 20140120 DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0120