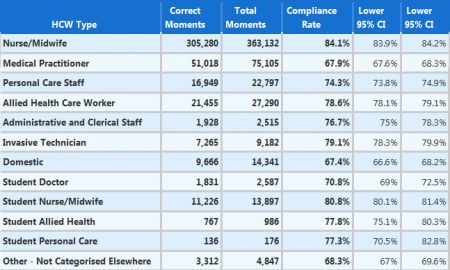

The latest statistics (see above, from Hand Hygiene Australia) show that doctors in Australian hospitals comply with hand washing requirements less than 70 per cent of the time. In the post below, ACT MP and former dentist Dr Chris Bourke asks whether or not it’s time we adopted a ‘zero tolerance’ approach on failure to comply. He points out a number of international policies and programs that have led to major improvements in hospital hygiene.

***

Dr Chris Bourke writes:

When I was a young dental student the importance of washing our hands was hammered into us.

We all knew the story of Dr Ignaz Semmelweis, the Hungarian doctor at Vienna General Hospital in 1847 who dramatically reduced deaths by infection of mothers after childbirth by the simple act of getting doctors to wash their hands before delivering babies.

I bet most medical students today also know this history. Yet there seems to be a disconnect after graduation when they are practising in hospitals.

Astonishingly the Australian benchmark for hand washing by staff is only 70 per cent – unwashed hands for 30 per cent of the time seems to be OK for our health authorities. This data is collected by hand washing monitors who record failures to comply with the rules, therefore some staff fail to wash their hands despite knowing they were being observed.

Public health experts estimate that the failure rate is much higher when staff are not physically checked. It gets worse: when observations are broken down by staff category it is the doctors who fail the most. Some studies have found that doctors in hospitals wash their hands as little as 60 per cent of the time, while the latest statistics from Hand Hygiene Australia (HHA) put compliance at about 68 per cent.

In contrast hospital dental clinics record the highest rates of hand washing with 89 per cent compliance – well ahead of emergency departments, neo-natal intensive care and renal units. Dentists could be proud of this achievement but a failure rate of 11 per cent is still not good enough.

The WHO recommends five moments for hand washing; before and after touching a patient, before and after a procedure, and after touching the patient’s surrounds. The US Centre for Disease Control estimates poor hygiene results in a whopping 1 in 25 patients with hospital acquired infections.

In Australia only the most deadly of hospital based infections, golden staph., is reported on the My Hospitals website. There are 1.35 staph infections per 10,000 patient bed days for major hospitals across the country. One estimate for hospital acquired infection in Australia is 180,000 per year causing an extra two million additional days in hospital.

Here in Canberra the story is no different to the rest of the country. The most recent audit period reported on My Hospitals website shows an estimated hand washing rate of 74 per cent for the June 2014 quarter at the Canberra Hospital. There were 41 cases of golden staph reported last financial year.

ACT Health has responded to these outcomes by working to ‘educate health professionals that hand washing was just as important in preventing the spread of disease and illness as other hygiene practices’.

There are plenty of overseas examples of how to get doctors and other health workers to wash their hands. Cedars-Sinai Medical Centre is a not for profit tertiary hospital in Los Angeles, about one third bigger than the Canberra Hospital. In 2013 Cedars-Sinai recorded an organisation-wide hand washing compliance rate of 98 per cent, a dramatic increase from their 70 per cent rate in 2010. This resulted from a policy change that hospital acquired infections should be eliminated, not merely reduced, and by incorporating hand washing compliance into employee performance assessment.

In 2010 the Princeton Baptist Medical Center, a tertiary hospital in Alabama that is about half the size of the Canberra Hospital, implemented radio frequency identity badges for all staff including doctors to record hand washing. Messages on the device’s screen sent general and personal messages to reinforce hand washing. Hospital acquired infections fell 22 per cent in the first year.

UPMC Presbyterian in Pittsburgh, about the same size as Canberra Hospital, launched a ‘Just Culture’ initiative in 2012 to change hand washing behaviour through accountability. Within four months hand washing compliance increased from 70 per cent to 99 per cent.

Here in Australia a recent study of management attitudes at an inner Sydney 350 bed tertiary referral teaching hospital found that hospital managers still want to debate if hand washing non-compliance constitutes a patient safety error. Managers prefer not to confront non-compliers with consequences for their hand washing failure.

Maybe, instead of a punitive approach, an opportunity exists to apply the restorative practice philosophy that has worked so well in education and juvenile justice. Restorative practice focuses on using shame within a continuum of respect and support to induce behaviour change (see Van Stokkom, B. 2002, “Moral emotions in restorative justice conferences: Managing shame, designing empathy”, Theoretical Criminology, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 339-360.).

Elements of restorative practice have already been successfully tried to improve hand washing; one US hospital appointed medical students as hand washing champions to remind senior doctors to wash their hands – doctor compliance improved from 68 per cent to 95 per cent within 6 months with senior doctors readily accepting the reminders.

Another study found that nurses’ hand washing intentions were influenced by peer pressure from doctors and administrators.

We must take action now to change attitudes and behaviours at our major public hospital to improve patient safety and quality of care otherwise we can expect more deaths and permanent disability from hospital based infections.

Dr Chris Bourke was elected to the ACT Legislative Assembly in 2011. He was the first Aboriginal Australian to complete a dental degree and has postgraduate diplomas in public health and clinical dentistry. He is a former President of the Indigenous Dentist’s Association of Australia, member of the Campaign for Indigenous Health Equality (Close the Gap), chairman of the Australian Dental Association (ACT Division) and Treasurer of the Public Health Association of Australia (ACT).