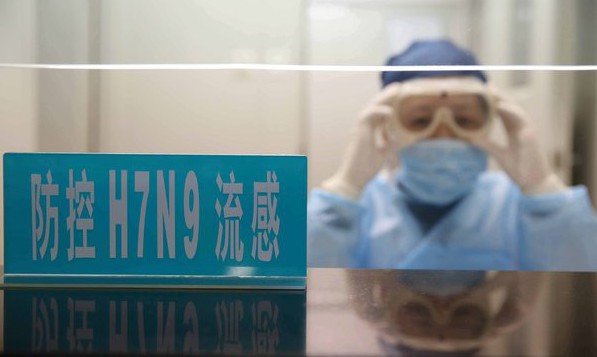

A deadly strain of bird flu that can infect humans has spread to different parts of China, is fast mutating and could end up as a pandemic, warn scientists after conducting the largest-ever genomic survey of the virus in poultry.

Now endemic in most regions of China, the H7N9 strain of avian virus is swapping genes with other types of flu viruses, giving rise to new strains, the researchers report in a paper published this week in Nature.

Any of the new strains could start a pandemic, scientists said.

The virus is entrenched in poultry populations across swathes of China, making it likely that people will continue to be infected sporadically. The researchers warn that it seems only a matter of time before poultry movement spreads this virus beyond China by cross-border trade, as happened previously with H5N1 and H9N2 influenza viruses.

“H7N9 viruses should be considered as a major candidate to emerge as a pandemic strain in humans,” the researchers write.

Taking swabs from birds at live poultry markets in 15 cities in five different eastern Chinese provinces, the researchers found evidence that the H7N9 virus is moving across China and gaining genetic diversity in the process. The virus was detected in markets in seven cities and in 3% of samples on average.

The team then sequenced the genomes of 438 viral isolates and found that as the virus spread south, it evolved into three main branches, with multiple sub-branches. They have found at least 48 different sub-types.

“The extent of viral transmission among chickens was largely unclear until our paper showed that the virus had diverged into regional lineages,” says Dr. Yi Guan, a co-author of the paper and a virologist at the State Key Laboratory of Emerging Infectious Diseases in Shenzhen, China.

Genetic changes

As flu viruses evolve and diversify in birds, genetic changes can alter their infectivity, virulence or ability to spread among humans, notes Guan. Human infections also provide viruses with opportunities to better adapt to their hosts.

The H7N9 has seen mutations that allow the virus to spread from birds to humans more easily than avian H5N1 flu, which has infected 784 people in 16 countries and killed 429 of them since it appeared in 2003.

While Guan’s team reported no further significant mutations in H7N9, the threat from H7N9 is unlikely to go away any time soon. The researchers point out that the frequency at which the virus is mutating increases the risk that the virus will acquire a dangerous mutation — potentially, one that could make it spread easier among humans.

The H7N9 bird flu virus emerged in humans in March 2013 and has since then infected at least 571 people in China, Taipei, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Canada, killing 212 of them, according to February data from the World Health Organization (WHO).

After an initial flare up of human cases at the start of 2013, the H7N9 appeared to die down — aided in large part by Chinese authorities deciding to close live poultry markets and issue health warnings about direct contact with chickens.

But infections in people increased again last year and in early 2015, prompting researchers to try to understand more about how the virus re-emerged, how it might develop, and how it might threaten public health.

As chickens exhibit no outward signs of being infected by the H7N9 virus, it is difficult to monitor and control poultry populations in large nationalized farms.

While humans can pick the infections from birds, the real danger comes with the virus accomplishing human-to-human transmission.

The H7 influenza subtype is one of a few influenza subtypes — there are around 18 discovered so far in all — that are known to infect mammals, making it a likely candidate for human-to-human transmission, but at this point transmission between people has been reported in only limited cases.

The reinventing of influenza viruses by constantly recombining in various genetic exchanges of eight RNA segments has raised alarm, with the World Health Organization warning recently of possible pandemics worse than the swine flu outbreak of 2009.

The health agency is particularly concerned about avian influenza, noting that the diversity and geographical distribution of influenza viruses currently circulating in wild and domestic birds are unprecedented. Over the past two years, H5N1 has been joined by newly detected H5N2, H5N3, H5N6 and H5N8 strains, all of which are currently circulating in different parts of the world.