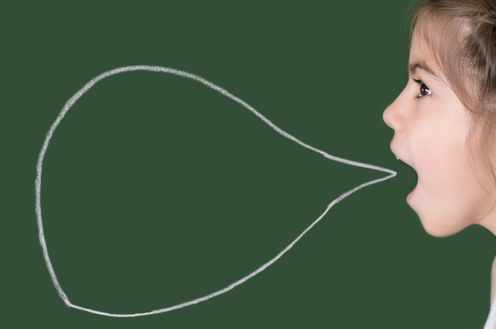

Speech problems in early childhood are common. One in four parents of Australian children are concerned about their 4- to 5-year-old child’s speech but two-thirds of these parents don’t act on their concern. Why? What might stop them from seeking expert advice from a speech pathologist?

Myth 1: Children grow out of speech problems (just look at Einstein!)

It is true that children’s speech development takes time. A young child does not pronounce words like “spaghetti” or “hospital” accurately the first time they say them. However, parents should not hold onto the idea that their child will grow out of speech problems just because Einstein turned out to be a genius.

Although there are anecdotes that Einstein’s parents were worried about his speech and language development, it has not been proven that Einstein had a learning disability or that he was late to talk. It is unhelpful for children struggling to develop clear communication skills to have parents reassure themselves to the point of inaction based on a false belief.

There is cause for concern when a 4-year-old child’s speech is difficult for other people to understand. If parents take the wait-and-see approach, they put their child at risk of experiencing persistent speech difficulties during the school years, an increased risk of slower progression with reading, writing and overall school achievement, bullying, poorer peer relationship, and less enjoyment of school compared with their same-age peers. The risks are greater when speech difficulties are accompanied by language learning difficulties.

Myth 2: Speech problems are caused by tongue-tie

Tongue-tie (ankyloglossia) exists when a person has a short lingual frenulum — the fold of mucous membrane that anchors or ties the mid-portion of the tongue to the base of the mouth. Prevalence ranges from 4% to 10%, with boys affected more than girls.

When severe, tongue-tie can decrease tongue mobility and impact breastfeeding. In a review of research on the effect of tongue-tie on breastfeeding and speech, there was no evidence to suggest a causative link between tongue-tie and speech problems.

Case reports suggest that tongue-tie may be a contributing factor for a small number of children who cannot produce the “l” or “th” speech sounds; however, for the vast majority of children with speech difficulties (including children who struggle with “l” and “th”), tongue-tie is not the cause of the problem.

It seems that the tongue-tie myth was started long ago by Aristotle when he suggested tongues that are slightly tied are linked to indistinct speech and lisping. This myth has perpetuated for millennia, leading to often unnecessary, unusual and bizarre practices for releasing the tongue.

Myth 3: Children who don’t speak clearly are lazy

This myth reflects a lack of understanding about the nature of speech problems in children and a lack of appreciation for the consequences of the problem. Consider the following example: 4-year-old Henry (pseudonym) says bus as “bus” but sun as “tun” and spoon as “poon”.

You might think that because Henry can produce the “s” sound in bus, he is being lazy when he doesn’t use “s” in sun and spoon. He’s not. Henry has the most common type of childhood speech difficulty — phonological disorder.

This difficulty exists when a child struggles to learn the grammar or rules about which speech sounds belong in the language they are learning and how those sounds combine to form words. When children begin to talk they make systematic rule-based changes to simplify their speech, so that complicated words are easier for them to process in their heads and say.

As adults we intuitively know many of these rules. For instance, “spaghetti” becomes “getti” because toddlers delete syllables in long words, and “look” becomes “wook” because toddlers replace difficult sounds with easier sounds. Phonological disorder exists when most of these simplifying rules do not disappear by around 4-years.

Given the repeated misunderstandings and frustration that children with speech difficulties face, it makes no sense to suggest that these children are lazy. The truth is, children like Henry have a phonological disorder that responds well to intervention by a speech pathologist.

Myth 4: Therapy for speech problems doesn’t work

With the right help from a speech pathologist at the right time, 3- and 4-year-old children with speech difficulties can develop clear speech and go on to have successful early reading and spelling experiences.

The myth that intervention does not work was sparked by the publication of a community-based study of speech therapy conducted in the United Kingdom, published in 2000. This study found little evidence for the effectiveness of speech and language therapy compared with watchful waiting, over a 12-month period. What is important to know about this study is that the children in the intervention group received on average just 6 hours of therapy over the 12 months. This was not enough.

It was akin to prescribing antibiotics and only offering a limited dose, rather than the prescribed dose. Research suggests that children, like Henry, can need 20 hours or more of therapy to improve their speech.

Findings from the recent Australian Senate inquiry into the prevalence of different types of speech, language and communication disorders and speech pathology services suggest that not all Australian children with speech difficulty are getting the right amount of help they need, at the right time.

The problem isn’t that interventions for speech problems don’t work. They do. The problem is that service and resource constraints can limit the amount of intervention that children receive.

If you are concerned about your child’s speech, don’t make decisions about your child’s future based on myths. Find out the facts and seek professional advice from a speech pathologist.

Elise Baker works for The University of Sydney. She has received grant funding from the Australian Research Council, and the New South Wales Department of Education. She is affiliated with Speech Pathology Australia.