Q: I was recently diagnosed with PCOS and heard that some people manage it through a low-carb diet. Is that true, and should I try it?

A: The short answer: not necessarily. But first, let’s take a step back.

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, or PCOS, is a hormone disorder that’s estimated to affect between one in 10 and one in 20 women of childbearing age, depending on how the disorder is diagnosed and what country is analyzed.

When hormone levels become disordered, the hormone insulin rises beyond healthy levels. This then stimulates the production of male sex hormones, which occur naturally in all women but rise too high in women with PCOS. This can interfere with other hormones in the body that regulate everything from ovulation and conception to hunger and weight gain.

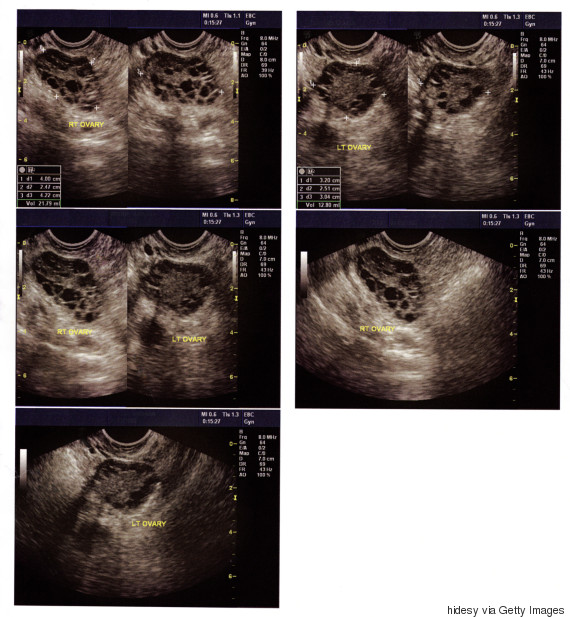

These irregular hormone levels manifest themselves in symptoms that range from irregular periods to acne to excess hair on the face, chest, and back, insulin resistance and little cysts on the ovaries (hence, the name), although you don’t have to have all the symptoms to be diagnosed with the condition.

PCOS is the most common cause of infertility in women, because it interrupts ovulation or makes it so erratic that couples can’t accurately time intercourse to a woman’s most fertile week. Because of its association with elevated insulin levels, PCOS is associated with increased risk of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Researchers aren’t sure which order of events happens first: For example, higher fat stores in an obese person lead to elevated levels of insulin and insulin resistance, so perhaps weight gain leads to PCOS. On the other hand, wacky hormone levels could be messing with hunger cues, which lead women to eat more and gain weight, so perhaps PCOS leads to weight gain. To complicate matters further, there is a small segment of women with PCOS who are of normal weight. What is known, however, is that the condition tends to run in families and has been called a “cousin” of diabetes, but not all women with prediabetes or diabetes has PCOS; instead, more than 50 percent of women with PCOS will be diagnosed with either diabetes or pre-diabetes before the age of 40.

For most women with PCOS, the first-line treatment for the condition is weight loss. Even losing just five to ten percent of one’s weight could help reverse some of the symptoms, but women with PCOS have a harder time losing weight than most. There’s even some evidence that PCOS causes increased hunger pangs, which leads to more eating and more weight gain.

Ultrasound showing typical ovarian cysts during Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS).

Which brings us to diet. Because the hormone disorder involves elevated insulin levels, researchers have suspected that cutting down on the sugars in dessert, starchy vegetables, carbs and dairy could help mitigate the effects of the hormone condition — and in fact, many women say that a low-carb diet has indeed worked to help them lose weight. But when it comes to a consensus about a low-carb diet for PCOS, the research isn’t definitive. Contrary to some of the advice doled out, there is no conclusive evidence that the condition can be controlled by following a single diet — in particular, the low-carb, high-protein diet touted by some PCOS clinicians.

In a 2013 review of five studies that enrolled 137 participants in total, research dietitian and PCOS expert Lisa Moran, Ph.D. of the University of Adelaide and Monash University found that it didn’t matter which diet women undertook to control their PCOS. As long as women lost weight, their PCOS symptoms improved.

“Different approaches have been studied in clinical trials, including higher protein, lower carbohydrate, higher unsaturated fat or lower glycemic index,” Moran told The Huffington Post. “The majority of evidence indicates no differences between dietary approaches, although some small trials report benefits of a low glycemic index/glycemic load approach or increasing omega 3 fatty acid intake.”

In other words, aside from perhaps some preliminary evidence that eating a low glycemic diet, which is an eating plan that emphasizes foods that don’t raise blood sugar levels, may help symptoms, any healthy diet that helps you lose weight is the right one to help control PCOS. Moran recommends that women who want to alleviate their PCOS symptoms visit a nutrition professional to help come up with a diet tailored to specific dietary needs and cultural preferences in order to build a longterm, healthy lifestyle.

And even if women with PCOS aren’t overweight or obese, maintaining a healthy diet and lifestyle to prevent weight gain is just as crucial, said Moran. “Weight is very closely tied to all the features of PCOS, and if a woman gains weight this will likely worsen her presentation [of symptoms],” she said. “Hence, prevention of weight gain is an ideal approach.”

Despite the fact that there is no conclusive evidence that one diet is better than others to help manage PCOS, Brie Turner-McGrievy, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health, has found that women with PCOS seem to think that a high-fat, high-protein diet is best for them and their condition. In a small but diverse study of 18 obese women with PCOS, she found that they were eating higher amounts of fat and lower amounts of whole grains and fiber than a comparison group of 28 overweight women without PCOS, but they didn’t experience any improvement in their symptoms.

“There’s some indication that maybe women with PCOS have gotten this message that they should be eating a lower carbohydrate diet, but we were seeing that this wasn’t beneficial for them,” Turner-McGrievy told The Huffington Post.

In a second experiment as part of the study, she took that same group of women with PCOS and randomized them to two different diets: half started eating a low-glycemic vegan diet, while the other began eating a simple low-calorie diet. Like the findings of Moran’s study review, Turner-McGrievy found that there was no statistically significant difference in weight loss between the two groups after six months, although the vegan dieters were actually eating less calories than the low-calorie diet.

But a more stark finding of her study was that participants dropped out of the research at rates of about 50 percent. Other PCOS researchers have also found participants with PCOS tend to have unusually large dropout rates from studies as compared to other weight loss studies. For Turner-McGrievy, that means scientists still haven’t found the best way to communicate and deliver weight loss regimens to women with PCOS.

“We don’t really know why a dietary intervention targeting women with PCOS would have more dropout,” concluded Turner-McGrievy. “I think along the lines of testing which diets are best, we also have to figure out… what’s going to resonate with them the most.”

What you can do now: In addition to modest weight loss, there are a number of pharmaceutical ways to address PCOS complications. Birth control pills can regulate menstrual cycles, diabetes drugs like Metformin can improve insulin resistance, and various fertility drugs can help women ovulate and conceive if they’re struggling to get pregnant. But while these medicines can moderate symptoms or help women achieve pregnancy, none of them truly “cure” PCOS. As Turner-McGrievy put it, “Similar to diabetes, once you have it, you’re mainly focusing on making sure you manage symptoms [so] it doesn’t get worse.”

Researchers still need to learn the root causes of PCOS, the best ways to help women with PCOS lose weight and maintain healthy weights and understand the psychological effects of the condition on women and their family members. But until then, working with your doctor to get the right combination of medicines, as well as establishing the routine of a healthy lifestyle, can prevent PCOS symptoms from worsening.

The condition was first described in 1935, but we still don’t understand the root causes of the condition in part because it’s so complex that even researchers disagree about how to classify and diagnose PCOS. Another issue, notes a letter to the editor of BMJ, is that when women cross the threshold into diabetes or cardiovascular disease, PCOS as a diagnosis may be set aside to focus on the new diseases.

As a PCOS researcher, Turner-McGrievy says it all contributes to a lack of funding to study the condition, which means there’s less opportunity to understand the disease or the best ways to help women with PCOS drop pounds and maintain healthy weights.

“Even though PCOS effects between 1 and 10 and 1 and 20 women, there isn’t a lot of research money dedicated to PCOS (vs. diabetes, cancer, heart disease, etc.),” said Turner-McGrievy. Indeed, a list of current National Institutes of Health-funded trials reveals that very few of them are examining how diet and exercise can prevent and treat PCOS, she noted. Until more information comes to light, working with your doctor to get the right combination of medicines, as well as establishing the routine of a healthy lifestyle, can prevent PCOS symptoms from worsening.