Australian research leaders have described their fear of losing “everything that we’ve worked for” and sending jobs and expertise overseas, amid a standoff between the government and the Senate over a crucial funding extension.

Scientists attended a Senate committee hearing on Friday to call on the government to release $150m that it has budgeted to continue the national collaborative research infrastructure strategy (NCRIS) beyond 30 June.

The education minister, Christopher Pyne, has sought to make the funding extension conditional on the passage of the contentious university fee deregulation package, arguing that if the program closed the loss of 1,700 jobs would be “on the heads of Labor, the Greens and the crossbenchers”.

Labor’s higher education spokesman, Kim Carr, asked NCRIS funding recipients who were attending the hearing on Friday to explain the implications “if the government persists with its blackmail of the Senate”.

Dr Michael Dobbie, chief executive of the Australian Phenomics Network, said the program had provided critical infrastructure for the Australian biomedical research fraternity.

“We spent eight years building this infrastructure – bringing together partners from diverse skills and expertise and instrumentation. It’s a unique partnering we see here in Australia and we’re really seeing the benefits from that,” Dobbie said.

“The human body is an amazingly complex and beautiful thing and to be able to study the body we need a complex and beautiful way to do that using the skills and expertise that are in front of us. No one institute or person can do that – we need to work together.”

Dobbie told the Senate’s education committee that scientists had poured their lives into these efforts, but some partners had “already dropped out” and “suspended their services waiting for news and certainty”.

He said an Australian National University facility that employed technical and management staff was about to advise 18 people that their contracts would not be renewed at the end of June.

Dobbie said the lack of funding certainty was “extremely frustrating” and he argued the worthwhile investment “really shouldn’t be jeopardised by other agendas”.

“It’s taken us eight years of building. We can’t just actually shut our shop because it involves live animals as well as the staff. There’s going to have to be a staged shutdown. We’ll lose everything that we’ve worked for,” he said.

“We really want to make sure that you understand that there is a lot at stake; we have leveraged a lot, we’ve got a lot of momentum, there’s a lot of trust and we have a huge amount of capacity which is now sitting at the edge of that cliff.”

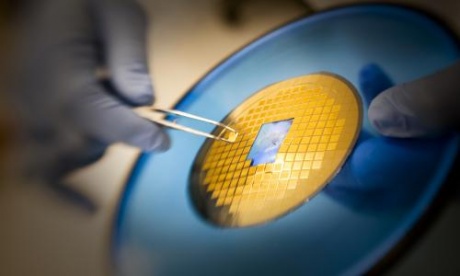

Rosemary Hicks, chief executive of the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF), said she was already being asked to provide references to experts who were looking for other opportunities. Some of those people would go overseas.

Hicks said the $150m in funding that the government announced in last year’s budget was “absolutely critical but it hasn’t been released”.

“I believe we need to get the funding released regardless of the current debate on deregulation of university fees,” Hicks said.

“We employ 94 people through NCRIS; our central administration is three of that. The rest are the technical staff, distributed across 21 institutions. We will begin closing those activities at 30 June and 75% of access to the capabilities will be gone by 30 September. The remainder will be gone by Christmas.

“In addition to the jobs directly funded by NCRIS, if I take for example just the Nanopatch, the creation of that company is 23 new jobs. That will no longer be carried out in Australia and they’ll have to find a way to take that product to market overseas. That’s just one example.

“About 25% of our access is on products that include industry partners so you can see an immediate knock-on effect to additional jobs.”

Professor Tim Clancy, director of the Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network, said 75 people were directly employed in “very skilled technical” positions but their jobs were at risk amid the uncertainty.

“We can’t emphasise strongly enough that this is a really important program and it is actually going to cost more to the economy and Australia by shutting it down than keeping it going,” he said.

“There’s a lot of impact on the staff. People are quite rightly proud of involvement in a high-value program and recognise that people see it as high value but the uncertainty is crippling. You see it, especially on junior staff, they’re now caught in this situation – what do they do – so it’s a very awkward time at the moment.”

Professor Chris Goodnow, of the Australian Phenomics Facility, said he was due in Washington in two weeks for a meeting “which gives us in Australia a seat at the table of the very cutting edge of genomics and biomedical research”.

“I’m going to be in the uncomfortable position of have to say that we may not able to continue to operate even though we’re only in the middle of a five-year landmark research program,” he said.

“We may have to look to move the Australian activities to Texas.”

Emphasising the importance of certainty, Goodnow said: “One of the things that NCRIS did incredibly well was to fund not just the shiny machines that go ping, but also the brilliant and very specialised technical staff that actually know how to make those things make real scientific music. Those staff are very specialised. You can’t just suddenly put them out in the pasture for a couple of years.”