Four patients at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center were infected by a drug-resistant bacteria after undergoing an endoscopic procedure with the same manufacture’s device that caused two deaths among seven infections at UCLA only a few weeks ago, officials announced Wednesday.

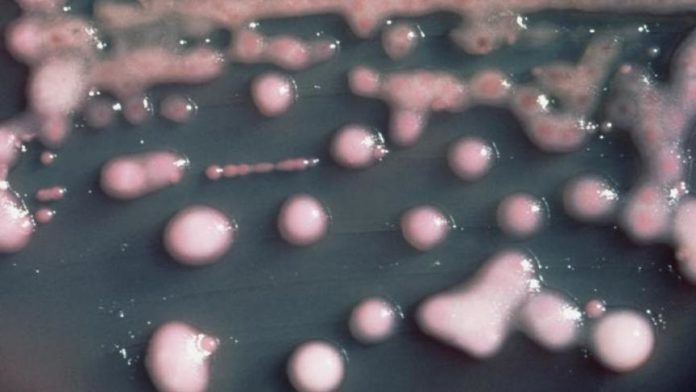

An investigation launched by the Los Angeles medical center’s infection-control specialists identified the four patients who had a CRE, or carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, transmission linked to a scope that has come under scrutiny because its design impedes effective cleaning.

One patient who had the infection died, but Cedars-Sinai officials said in their statement that the patient died because of another underlying condition.

The same scope was used in all four patients whose procedures were done between August and January. The medical center also is sending out letters and home testing kits to 71 more people who had the duodenoscope procedures with the same scope between August and last month.

Cedars-Sinai officials said they removed the scope in question and are “continuing to use enhanced disinfection procedures for duodenoscopes, above and beyond the manufacturer’s recommendations,” according to a hospital statement.

The medical center’s announcement comes two weeks after Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center notified almost 200 of their patients that they may have been infected by the drug-resistant bacteria after undergoing an endoscopic procedure.

In response to UCLA’s announcement, the FDA cautioned that the device, made by Olympus Corp., should be cleaned beyond previously approved standards.

“Due to its complex design, it is difficult to effectively clean a medical device known as a duodenoscope that is used during a potentially life-saving procedure known as Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP),” the FDA said in a statement on Wednesday.

But the federal agency also has come under the spotlight because it had already documented evidence that there were design issues with the scopes. From January 2013 through December 2014, the FDA received 75 medical device reports involving about 135 U.S. patients relating to possible microbial transmission from reprocessed duodenoscopes.

“Residual body fluids and organic debris may remain in these crevices after cleaning and disinfection,” the FDA said in an alert issued two weeks ago. “If these fluids contain microbial contamination, subsequent patients may be exposed to serious infections.”

The scope is used during a procedure to diagnose and treat pancreatic diseases. The bacteria, known as CRE, can also be transferred from a patient to the hands of the care provider, like a doctor or nurse, and from their hands to another patient. Healthy people aren’t typically at risk for becoming infected with CRE; the bacteria tends to strike patients with compromised immune systems who are receiving treatment through catheters and ventilators. Those patients are already vulnerable to begin with, and about half of them die once they’re infected with CRE. The World Health Organization (WHO) has designated CRE as one of the greatest threats to human health, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls it a “nightmare bacteria.”

The medical community has been concerned about CRE for the past decade as drug resistant bacteria have quickly become a global public health threat. The first recorded CRE case in the United States occurred in 1996 in North Carolina, and by 2006, it had already appeared in almost every state across the country.

According to a 2014 a study published in the journal Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, CRE infection rates are “increasingly dramatically” in community hospitals across the southeastern United States. The analysis, which looked at five years of data (from January 2008 through December 2012), found that there was a fivefold increase in the number of cases of the superbug during the study period.

Currently, an estimated 9,300 people in the U.S. are infected by CRE every year. In total, various superbugs cause more than 2 million infections resulting in more than 23,000 deaths annually in the U.S, according to the CDC. But if more and stronger action isn’t taken soon to address the growing issue of superbugs like CRE, evidence suggests we could face serious consequences: By 2050, these infections could kill 10 million people worldwide — more than all types of cancer, combined.