It sounds cruel to put an already hungry teenager in an MRI scanner and show him pictures of burgers, fries, pizzas, syrupy waffles and ice cream cones. But thanks to 34 willing teens, researchers have found a new way to help adolescents trying to achieve a healthy weight.

“The promising piece is that it appears we can help people to learn how to make better choices about food,” said Dr. Chad Jensen, the study’s first author and a psychologist at Brigham Young University.

In the experiments, three groups of teenagers fasted for four hours before viewing images of healthy and unhealthy foods during a brain scan. One group consisted of overweight teens. A second group was comprised of formerly overweight teens who had lost weight and kept it off for at least a year. The third group of teens had historically maintained a healthy weight.

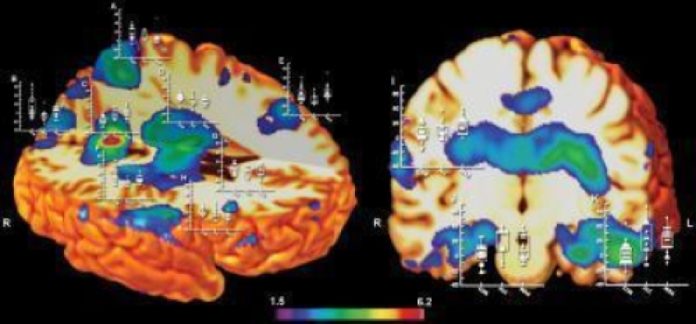

As the teens looked at the food pictures, neuroscientists looked at which areas of their brains lit up. Specifically, they measured activity in the pre-frontal cortex where a process known as “executive function” resides. Executive function is the ability to process and prioritize competing interests.

When high-calorie foods were shown, the group of formerly overweight teenagers showed the highest activity levels in this region. That means they relied on the executive function processes more than the other groups, which may explain why they succeeded in losing weight.

“You can improve executive control,” said study co-author Dr. Brock Kirwan, a neuroscientist at BYU. “Successful programs involve repeated practice and ramping up the challenges to executive control, kind of like successful exercise programs.”

The study authors note that a variety of activities can improve children’s executive functions: computerized training, games, aerobic physical activity, martial arts and yoga. In addition to challenges that increase over time, an emphasis on delayed rewards is also critical.

The study — which appears in the scientific journal Obesity – is the first publication to come from data collected at BYU’s new MRI facility. Among many other ongoing projects, Drs. Jensen and Kirwan plan to do follow-up research on executive control and weight loss. In the future, one question they’d like to answer is how a generalized training on executive function compares to a food-specific regimen.

The new research adds to a growing body of evidence indicating that the causes of obesity are much more complex than previously thought. The findings are also in line with another recent study that identified more than 100 new genetic contributors to obesity, including several in the areas of the brain involved in executive functioning. Based on the evidence, scientists believe the pre-frontal cortex likely plays a key role in regulating appetite signals that tell us when we are hungry and when to stop eating. Supporting that idea, research has linked deficits in executive functioning to overeating, while other studies have uncovered similarities in the brain processes underlying obesity and addiction.

While diet and exercise will always be key for preventing and treating obesity, more and more evidence points to a need to consider the biological mechanisms that could be driving excess weight gain and fat storage in some people. Perhaps one day, society at large will also stop pinning obesity on laziness and poor choices…