There’s little comforting about phrases like “nightmare bacteria” or “fatal superbug”. Reports like those surrounding the recent exposure to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Los Angeles are understandably alarming, especially considering almost 200 UCLA Medical Center patients may have come in contact with such a bug.

This exposure and resulting infections raise many questions: Will more patients become infected? What will become of the medical devices implicated? How worried should we realistically be?

If more and stronger action isn’t taken soon to address the growing issue of superbugs like CRE, reports suggest we could face serious consequences: By 2050, these infections could kill 10 million people worldwide — more than all types of cancer, combined.

CRE bacteria, which can withstand treatment from virtually every type of antibiotic. (AP Photo/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

1. What do you mean, “superbug”?

It’s no medical term, but colloquially it’s come to represent a class of dangerous microbes, generally bacteria, that have mutated in a way that help them to resist the medications we most frequently use to treat them. This is why superbugs are also often referred to as drug-resistant or antibiotic-resistant. They’ve spawned the ability to outsmart our best line of defense against the infections they cause.

2. Why do they mutate like that?

Like any living organism, bacteria can mutate as they multiply. Also like any living organism, bacteria are driven to survive. So, a select few will mutate in particular ways that make them resistant to antibiotics. Then, when antibiotics are introduced, only the bacteria that can resist that treatment can survive to multiply further, proliferating the line of drug-resistant bugs.

3. Why are we hearing more about superbugs now?

Infections seem to be on the rise. At least 2 million people become infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria a year in the U.S., and an estimated 700,000 die from such an infection worldwide. Without additional methods of treating superbugs, that number could reach 10 million by 2050. One recent study found that CRE infections were five times as likely in 2012 compared to 2008.

4. How much is the average healthy person at risk?

Drug-resistant infections are more common in hospital or other health-care settings. People who are already seeking medical attention may have weakened immune systems that leave them more susceptible to infections. CRE infections have only been seen in a health-care setting, USA Today reported. But others can occur outside of hospitals. MRSA, for example, one of the most well-known drug-resistant superbugs, is on the decline overall, although increasing outside of hospitals. It’s important to keep in mind that infection is a possible risk of any surgical procedure, but only occurs in about 1 percent of cases, WebMD reported.

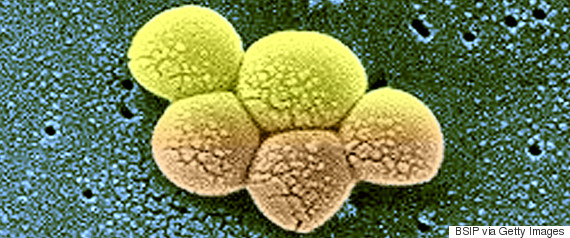

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, bacteria (Photo By BSIP/UIG Via Getty Images)

5. So what should I do to protect myself?

Because there are limited treatment options (because these infections are resistant to antibiotics), prevention is the best measure. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) urge patients concerned about drug-resistant infections to stay up-to-date on vaccines, to help you stay healthier overall and out of medical facilities in general. Careful hand-washing in a hospital setting should be a regular practice. But perhaps most importantly, you can avoid unnecessary treatment with antibiotics. Taking antibiotics when they are not needed can up your risk of drug-resistant infection down the line, according to the CDC, which estimates that antibiotics are “not optimally prescribed” as much as 50 percent of the time. Remember: Antibiotics do not fight viruses, so please do not try to bully your doctor into writing you a prescription when you have the flu.

6. Are some superbug infections more serious than others?

Yes. The CDC lists three urgent threats: CRE, responsible for about 9,000 infections a year, C. difficile, which causes about 250,00 cases of life-threatening diarrhea a year, and neisseria gonorrhoeae, which causes around 246,000 cases of drug-resistant gonorrhea a year. These most critical concerns are followed by 12 slightly less serious threats that are expected to worsen, however, including bacteria that cause diarrhea, meningitis, tuberculosis, blood infections and more.

A rod-shape E. Coli bacterium (Photo By BSIP/UIG Via Getty Images)

7. What about antibiotics in food?

Yes, the germs that contaminate our food can also become drug-resistant. Antibiotics are sometimes given to food animals to cause them to gain weight quickly, which could contribute to growing antibiotic-resistance. In fact, a particular strain of drug-resistant E. coli seems to be causing more urinary tract infections than in the past, and some researchers believe chickens are the source. Eating chicken carrying drug-resistant E. coli delivers the bacteria to a person’s gut and could eventually end up causing an infection — and indeed, studies show genetic similarities between the E. coli found in chicken and in people with UTIs, Everyday Health reported. Others argue this E. coli could originate in humans but make its way to animals through the sewage system.

Also on HuffPost:

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Vortex Green 2 Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Additional A colony of the chiral morphotype of the Paenibacillus dendritiformis bacteria. Note that the branches have a well defined handeddnes – hence the term chiral. The colony diameter is 7 cm Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Bacterial dragon The same as previous but for different growth conditions (level of food and surface hardness) Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Vortex red Close look at a colony of the P. vortex bacteria Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob These pictures belong to a series of remarkable patterns that Paenibacillus vortex and Paenibacillus dendritiformis bacteria form when grown in a Petri dish under different growth conditions. While the colors and shading are artistic additions, the image templates are actual colonies of tens of billions of these microorganisms. The colony structures form as adaptive responses to laboratory-imposed stresses that mimic hostile environments faced in nature. They illustrate the special strategies that bacteria have developed over the course of evolution, strategies that involve cooperation through communication. To develop such complex pattern the individual cells collectively manipulate the overall colony organization (composed of billions of cells) for the group benefit.

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Dendrtiformis C 2 Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob

-

![Bacteria As Art]()

Eshel Ben-Jacob