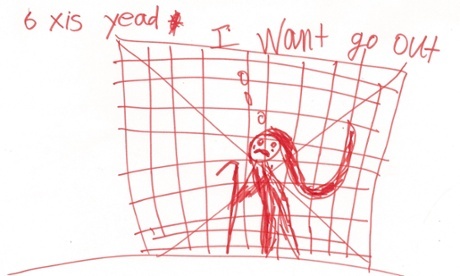

More than 300 children committed or threatened self-harm in a 15-month period in Australian immigration detention, 30 reported sexual assault, nearly 30 went on hunger strike and more than 200 were involved in assaults, a damning report from the Australian Human Rights Commission has found.

The long-awaited inquiry into children in immigration detention report, The Forgotten Children, found detention was inherently dangerous for children, and that “prolonged detention is having profoundly negative impacts on the mental and emotional health and development of children”.

“At the time of writing this report, children and adults had been detained for over a year on average.”

There are 257 children in Australian immigration detention, including 119 on Nauru. More than 100 children, previously held on Christmas Island, have been released into the community on the mainland on bridging visas over the past fortnight.

“It is the fact of detention, particularly the the deprivation of liberty and the high numbers of mentally unwell adults, that is causing emotional and developmental disorders amongst children,” the report said.

“Children are exposed to danger by their close confinement with adults who suffer high levels of mental illness. Thirty per cent of adults detained with children have moderate to severe mental illnesses.”

Between January 2013 and March 2014, children in immigration detention were involved in:

- 128 incidents of actual self-harm;

- 171 incidents of threatened self-harm;

- 33 reports of being sexual assaulted;

- 27 cases of voluntarily starvation or hunger strike.

Under international and Australian law, children are supposed to be detained only as a measure of “last resort”.

Australia is the only country in the world that mandatorily detains all unlawful non-citizens, including children.

Australia also holds children in indefinite detention if a parent has an adverse Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (Asio) security finding made against them.

“Some children have been detained for longer than 19 months because at least one of their parents has an adverse security assessment by Asio,” the report said. “The indefinite detention of these children raises special concerns for their physical and mental health, and their future life opportunities.”

The report raised particular concern about children on Nauru.

“Children on Nauru are suffering from extreme levels of physical, emotional, psychological and developmental distress. The commission is concerned that detention on Nauru is mandatory for children and there is no time limit on how long they will be detained.”

Triggs’ report cited evidence to the commission from the then immigration department secretary, Martin Bowles, who told an inquiry hearing the damaged caused to children by detention was known to the department.

“There is a reasonably solid literature base which we’re not contesting at all which associates a length of detention with a whole range of adverse health conditions.”

In 2004 the Human Rights Commission launched A Last Resort?, a three-year inquiry into children in detention. In the aftermath of that report, the Howard government released all children from immigration detention.

In the current report, Triggs expressed disappointment that Australia had since regressed in its treatment of asylum seeker children.

“At the time of the previous national inquiry, the number of children in detention peaked at 842 children. In July 2013, just before the change of government, a record number of 1,992 children were in detention.”

Triggs condemned both Labor and Coalition governments for ignoring their stated commitments and legal obligations to protect children in their care.

“How had the gains that were so hard-fought at the time, and of which the Howard government were so rightly proud, disappear?

“How did we move so far away from the explicit guarantee … that ‘a minor shall only be detained as a measure of last resort’? How had we reached the situation where prime minister Rudd declared that any person (including children) who arrived by boat would enjoy ‘no advantage’ and never be settled in Australia?”

Triggs also said her commission was subject to “intense scrutiny and hostility” for conducting the inquiry: “The government at the time was initially dismissive of its findings.”

Immigration department statistics list 257 children in detention, including 119 on the island of Nauru.

There are also 28 unaccompanied child refugees, who have been released from detention to live in the community on Nauru.

Some children in detention over recent years have turned 18 and are no longer counted among child detention statistics, but are still detained.

More than 100 children, previously held on Christmas Island, have been released from detention in the last fortnight, part of the deal the government struck with Senate crossbenchers in return for their support for temporary protection legislation, passed in December.

ChilOut’s campaign coordinator, Claire Hammerton, said the report demonstrated a “dramatic failure” by successive governments to protect children in their care.

“The report confirms so many of our worst fears about the impact of detention on children. Disproportionately high rates of severe mental illness, high rates of self-harm, young children denied access to medical treatment such as hearing aids and glasses for prolonged periods. This is nothing short of state-sanctioned abuse.”

Hammerton said she was particularly concerned by children still detained on Nauru and those released to live unaccompanied in the community there.

“These children have been stripped of all hope as a result of their indefinite detention, and the findings of the Australian Human Rights Commission make it very clear that the most basic needs of these children – including access to drinking water and basic hygiene – are not being met. It is unconscionable that any government could allow children to live under these conditions, particularly when both sides of government have acknowledged that detention is not a deterrent.”

The Reverend Elenie Poulos, the national director of Uniting Justice Australia, said the findings of the report were a national disgrace.

“The report describes how children are woken every day at 11pm and 5am by guards shining a torch light in their faces as they conduct headcounts. Children are being toilet trained in filthy conditions.”

She said the living conditions on Christmas Island – where families were housed in shipping containers – were grossly inadequate.

“Dozens of children with physical disabilities and mental illness have received inadequate care and 100 children on Christmas Island had no education for over one year. Over 30% of children and parents interviewed described themselves as ‘always sad and crying’,” Poulos said.

“A family in which both parents and their child are profoundly deaf were denied hearing aids for seven months, so the parents couldn’t hear the cries of their child.”

Unicef Australia said mandatory and indefinite detention of children exposed them to sexual violence and abuse, as well as causing significant mental and physical illness and developmental delays.

“The findings of the Australian Human Rights Commission report are expected to confirm what is already known globally: detention is a dangerous place for children and can cause life-long harm,” Unicef’s Amy Lamoin said.