The headline death toll of Ebola “does not do justice to the profound and far-reaching impact of this disease”, says Greens Senator Richard Di Natale in his powerful report to Parliament on his recent trip to Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The headline death toll of Ebola “does not do justice to the profound and far-reaching impact of this disease”, says Greens Senator Richard Di Natale in his powerful report to Parliament on his recent trip to Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Read his speech below or watch it via the link here:

Empathy in an Age of #Ebola: @RichardDiNatale reports on his trip to Liberia and Sierra Leone to the @AuSenate http://t.co/ADyuA1e5oX

— Matthew Rimmer (@DrRimmer) February 10, 2015.

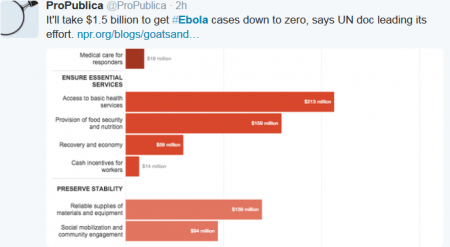

Di Natale’s trip included a visit to the Aspen Medical treatment facility which was Australia’s very belated response last year to the crisis. The Australian Government followed that up with an $11 billion cut to foreign aid, putting our contribution at an all time low (and prompting the #saveAustralianaid campaign – see pic, right) despite the clear urgent need with Ebola alone for substantial investment into the health services of affected developing countries.

See also this ‘The toll of the tragedy’ report from The Economist which notes:

The inadequacies of the health-care systems in the three most-affected countries help to explain how the Ebola outbreak got this far. Spain spends over $3,000 per person at purchasing-power parity on health care; for Sierra Leone, the figure is just under $300. The United States has 245 doctors per 100,000 people; Guinea has ten. The particular vulnerability of health-care workers to Ebola is therefore doubly tragic: as of February 1st there had been 822 cases among medical staff in the three west African countries, and 488 deaths.

***

Richard Di Natale’s speech:

In December last year I visited the countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone to monitor the international response to the Ebola epidemic. As a former doctor who has worked in international public health and now, as a federal senator with a platform that few others enjoy, I had a responsibility to bear witness to what was going on in West Africa. It was an opportunity to listen to people’s stories, to better understand the outbreak and to identify areas where Australia might better contribute. Ultimately I felt compelled to visit largely because of Australia’s inaction and a feeling of wanting to do more.

I reflect on that experience with mixed feelings. There is a deep sadness that comes from watching an orphaned infant in isolation being comforted by someone in a protective suit; from hearing the wailing of a grieving woman who is watching a burial team carry away a loved one in an orange body bag; or from seeing young kids playing, knowing that they are some of the ten thousand orphans who have lost their parents to this terrible disease.

But there were some uplifting moments, too, like the courage of the West African people at the front line of this effort. They are people like the West African ‘hygienists’, the people who are responsible for cleaning down the vomit and other wastes, disposing of all the infectious material and decontaminating and removing dead bodies from treatment centres; or people like the midwives at Liberia’s largest hospital who continued to deliver babies right through the peak of the epidemic while doctors around them died. When you think that Ebola is transmitted through exposure to body fluids, these people are working some of the most dangerous jobs on earth.

We have now seen a total of almost 22,500 cases of Ebola. We have seen 9,000 people dead. But that headline figure does not do justice to the profound and far-reaching impact of this disease. There are countries that rank near the bottom of the Human Development Index—some of the poorest countries on earth—where, on the back of civil wars, Ebola has wrought further havoc across the health and education sector.

In each country, the health system was barely functioning before the outbreak, and all are now near total collapse. Hospitals in both countries are either closed or barely functioning. There have been a number of doctors who have died; in fact, some of the most senior doctors in the biggest hospital in Monrovia in Liberia have died as a result of Ebola. Not only have they lost doctors but doctors and mentors who are responsible for training the next generation, so it is a double blow.

It has had an impact on the health system more broadly. When you consider that Sierra Leone, for example, has the highest under-five mortality rate in the world, we are now seeing childhood immunisation rates plummet even further. A number of people are now dying as a result of the impact of Ebola on the health system. While they will not be counted in the official death toll, they are directly attributable to this outbreak.

In education things are just as grim. Schools and universities were completely shut down; the school buildings were used as holding centres. Many of the kids who were going to school have now started working and they will be lost to the school system for good. We spoke to NGO workers who told us that a whole generation of young kids are now lost completely to the education system. On the economy, the World Bank estimates that the impact on the three most badly affected countries, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, will be US$1.6 billion in forgone economic growth in 2015.

We are making some progress. Most of the progress is a consequence not just of the treatment that is being provided but of the huge public health that is happening. We have workers and volunteers educating people about transmission, identifying new cases, tracing contacts and restricting the spread of the disease.

One of the challenges is that it is a disease spread through love, through human contact. People most at risk are the parents or siblings looking after somebody dying from this disease. The instinct is to reach out, to care for, to console—indeed, to clean—somebody who is vomiting or suffering from severe symptoms of this. It is very hard to resist. Imagine having a loved one who is sick or ill and not being able to engage in any physical contact with that person. That is why it is such a challenging disease.

The impact on those people who do survive is also traumatic. When you consider that half the people who are infected will survive, many of them will return to their communities—but they are often shunned. There is the sense that they might infect others. It is a sad irony, because they are people who are now immune from the disease and could be used to help combat the spread of the illness. It is a cruel double blow. Now we are seeing signs of post-traumatic stress disorder on survivors, carers and health workers.

It was really great to see the many Australians in the field who are making a contribution to the fight against Ebola. We have Australians working at every level. Some of them head global organisations, like the World Health Organisation and UNICEF. They are leading the charge working with NGOs. Many of them are on the front-line themselves—doctors, nurses and logisticians—and are providing health care in very high-risk settings. It was really inspiring to see the work they are doing.

It must be said that the Australian government is not flavour of the month in West Africa at the moment. I was shocked at how many people noticed some of the things that our government had done or had not done. The thing that raised the ire of most people was Australia’s unilateral decision to impose travel restrictions that do nothing to protect people from Ebola. They do not improve people’s safety. They do not contain the spread of the disease. All they do is spread fear and information about the disease. I remember speaking to an aid worker who was really frustrated by the announcement around travel restrictions. He told me it was the first time after 20 years of aid work that he had not felt welcome returning home from a mission.

It is true that Australia did make a small and reluctant contribution by awarding Aspen Medical the contract to staff a treatment facility. I have expressed concerns about how that contract was awarded and I was grateful to be offered a tour of the facility. I met with the operations manager, Daniel Kerr. It must be said that the work they were doing was of a high standard, that the training they were offering to their team—and I met with the training facilities there—again was of a high standard. They were doing all the right things in the lead up to opening up the training centre.

The danger is that with Ebola now almost absent from the headlines, there is a perception that things are under control and that we do not have to do any more. But there is a note of caution here. This was the first week where we have seen an increase in the number of cases for this year, with 124 new confirmed cases reported in the week to 1 February. What is most disappointing is all this is preventable.

When you see what the UK government, for example, are doing it is hard not to be impressed by their work and to feel that Australia’s reputation for responding early to disasters with significant humanitarian assistance is now being undermined. I do not know how you can fathom a cut in the aid budget when you bear witness to what is happening in West Africa. It is not a natural disaster. It is a disease fostered by poverty, through lack of water, sanitation and access to health care.

We have not been there during the crisis, but we can step up and make an impact in rebuilding the country. We need to commit more financial resources, more technical expertise and commit to long-term development and assistance. One thing we could do is support Oxfam’s call for a multi-million dollar post-Ebola Marshall plan to put the three West African countries hit by the crisis back on their feet. If we are going to do this, we have to recognise that these are people like you and me. We share a common humanity. Their lives are no less important.